Sir Shridath Ramphal, with support from several international lawyers, yesterday morning argued at a historic hearing before the World Court that it has the jurisdiction to decide that the Paris Award which settled the boundary between Guyana and Venezuela is valid and binding.

During the three-hour hearing Sir Shridath, Canadian Professor Payam Akhavan, US lawyer Paul Reichler and British-French lawyer Phillipe Sands presented the Court with a detailed history of the controversy beginning with the 1897 Treaty of Washington which established the tribunal that negotiated the award and concluded with Guyana’s application to the Court in 2018.

The legal team was supported from Ramphal House in Georgetown, by Co-Agents Carl Greenidge and Ambassador Audrey Waddell as well Gail Teixeira, Rashleigh Jackson, Cedric Joseph and Elisabeth Harper.

Sir Shridath led the pleadings with a one-hour presentation in which he reminded that it was Venezuela with the support of the United States which instigated the process that led to the 1899 Paris Award. He argued that based on the plain language of the 1966 Geneva agreement and the decision of the United Nations Secretary General (SG) the Court has the right to hear and deliberate on this matter.

“Guyana’s case is based in the plain text of the Geneva Agreement by which the parties expressly consented to accept the decision of the SG on the means of resolution of (the controversy) over the validity of the 1899 award including judicial settlement by this Court and that the (controversy) shall be settled by the International Court of Justice if that be the means chosen by the SG,” Sir Shridath stated.

The Secretary General, Sir Shridath stressed, has exercised that option and selected the Court.

“[After] almost 60 years of Venezuela trying and failing to spoil the sanctity of the Treaty of Washington and to nullify the Paris Award, the Secretary-General of the United Nations indicated to the Presidents of Guyana and Venezuela in these words and I quote ‘I have fulfilled the responsibility that has fallen on me within the framework set by my predecessor and significant progress not having been made toward arriving at a full agreement for dissolution of the controversy, I have chosen the International Court of Justice as the means that is now to be used for its solution.’ That is why we are here, attended by the faith of the people of Guyana in this international Court of Justice and in the rule of law internationally,” he explained.

The international jurist who as Guyana’s first Attorney General was present for the signing of the 1966 agreement expressed disappointment at Venezuela’s decision not to participate in the hearings.

“Undoubtedly, it would have been more helpful to the Court for both parties to appear to fully present their arguments in the first round and respond to each other in second but at least the Court has not been left to speculate as to what Venezuela might have said had it appeared in this Great Hall of Justice,” he noted in acknowledgment of a submission made by the Bolivarian Republic.

Sir Shridath explained that while Venezuela did not submit a counter memorial the state did submit a 56- page memorandum and 155 page annex setting out the basis for their objections to the Court’s jurisdiction and more.

Guyana used the time afforded by the Court to respond to all these claims in an attempt to demonstrate that they are without foundation.

Demonstrably erroneous

Specifically, Reichler in providing an analysis of the Geneva agreement and the UN dispute resolution mechanism explained that the three arguments presented by Venezuela in their submissions are demonstrably erroneous.

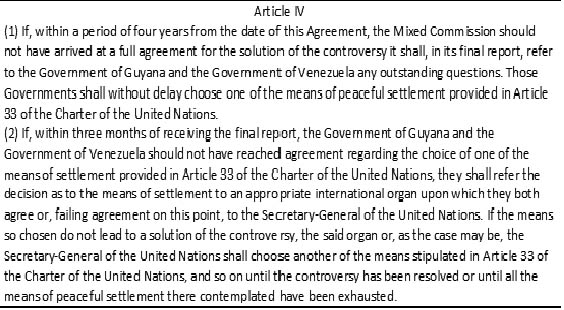

The first argument presented via a letter from President Nicholas Maduro claimed that the Geneva Agreement provided for settlement only by means of “friendly negotiations”. Reichler countered that while Article III of the Geneva Agreement does provide for friendly negotiations, Article IV provides other means of settlement should these fail.

“His reading ends too soon…. It is like they stopped reading the book of Genesis after the fifth day,” he posited before moving on to the second contention.

In its memorandum to the Court, the Bolivarian Republic, contradicts its first argument and claims that judicial settlement was established as a last resort within the 1966 agreement.

Specifically they accused the UN SG of attempting to unilaterally impose what should be the last resort.

Sands stressed that there is nothing in Article IV of the Agreement or Article 33 of the UN Charter which requires the SG to choose the means of settlement in any particular order.

“The only limitations to the power of the SG to decide on the means of settlement are first he must choose from among those listed in Article 33 and second if the means first chosen failed to resolve the controversy he must choose another until the controversy is resolved or the means are exhausted,” he reminded.

This counterargument is a direct quotation of Article IV (2) of the Geneva Agreement which states that the parties “shall refer the decision as to the means of settlement to an appropriate international organ upon which they both agree or, failing agreement on this point, to the Secretary-General of the United Nations. If the means so chosen do not lead to a solution of the controversy, the said organ or, as the case may be, the Secretary-General of the United Nations shall choose another of the means stipulated in Article 33 of the Charter of the United Nations, and so on until the controversy has been resolved or until all the means of peaceful settlement there contemplated have been exhausted.”

The wording of this Article drew the attention of one member of the Court, Judge Mohamed Bennouna of Morocco, who asked that Counsel address whether there could possibly be a situation where all peaceful means of resolution were exhausted without the controversy being settled.

The means listed in the Article are negotiation, enquiry, mediation, conciliation, arbitration, judicial settlement, resort to regional agencies or arrangements, or other peaceful means of their own choice.

Guyana has been granted until Monday at 6 pm to respond in writing to Bennouna’s question.

The third and final argument from Venezuela is that even if the SG could refer the matter to the ICJ and even if he could do so before exhausting all other means his decision was not binding because it required mutual consent before it could take effect. Absent this consent they argue it “can only be taken as a recommendation”.

Reichler told the Court that this entirely new reading of Article IV (2) is not only inconsistent with the text which refers to the SG choice as a “decision” but is also contrary to the position of their then Foreign Minister who in 1966 told the National Congress that “there is an unequivocal interpretation that the selection of the means of settlement will be made only by the Secretary General of the United Nations.”

Detailed history

The hearing aside from presenting the ICJ with clear explanation of the basis of its jurisdiction also provided a detailed history of the controversy.

Professor Akhavan detailed the origin of the controversy and the circumstances leading to conclusion of 1966 Geneva agreement.

He explained that as early as 1840 Venezuela attempted to claim the Essequibo River as the boundary of its territory. Britain’s refusal to accept this position saw the matter devolve into the 1895 diplomatic crisis when an advocate for Venezuela argued that it was a violation of the 1823 Monroe Doctrine.

Under threat of war from the United States of America, Britain capitulated and signed the Treaty of Washington.

Akhava told the Court that this action was a notable instance of peaceful dispute settlement in a historical period when recourse to war was a continuation of politics.

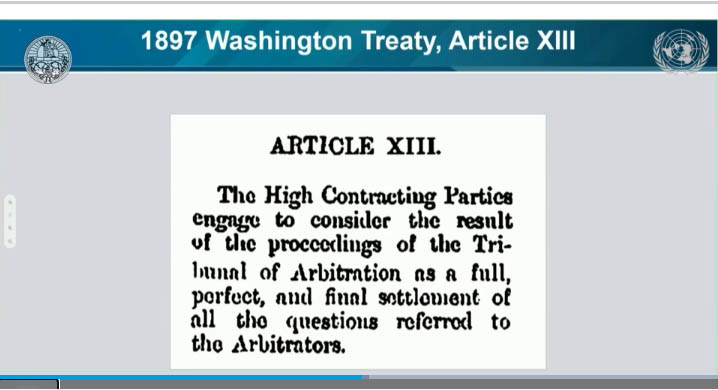

He explained that Venezuela called for and received international arbitration with the 1897 treaty instituting the tribunal and establishing as its objective “a full, perfect and final settlement of all questions referred to the arbitrators.”

Finally after 54 meetings which examined among other things 300 years’ worth of documentation, the tribunal on October 3, 1899 unanimously signed the award.

At that time it was widely celebrated as a victory for Venezuela with its Minister in London writing: “Greatly indeed did Justice shine forth when in the determination of the frontier we were given the exclusive dominion over the Orinoco which was the principal aim we sought to achieve through arbitration.”

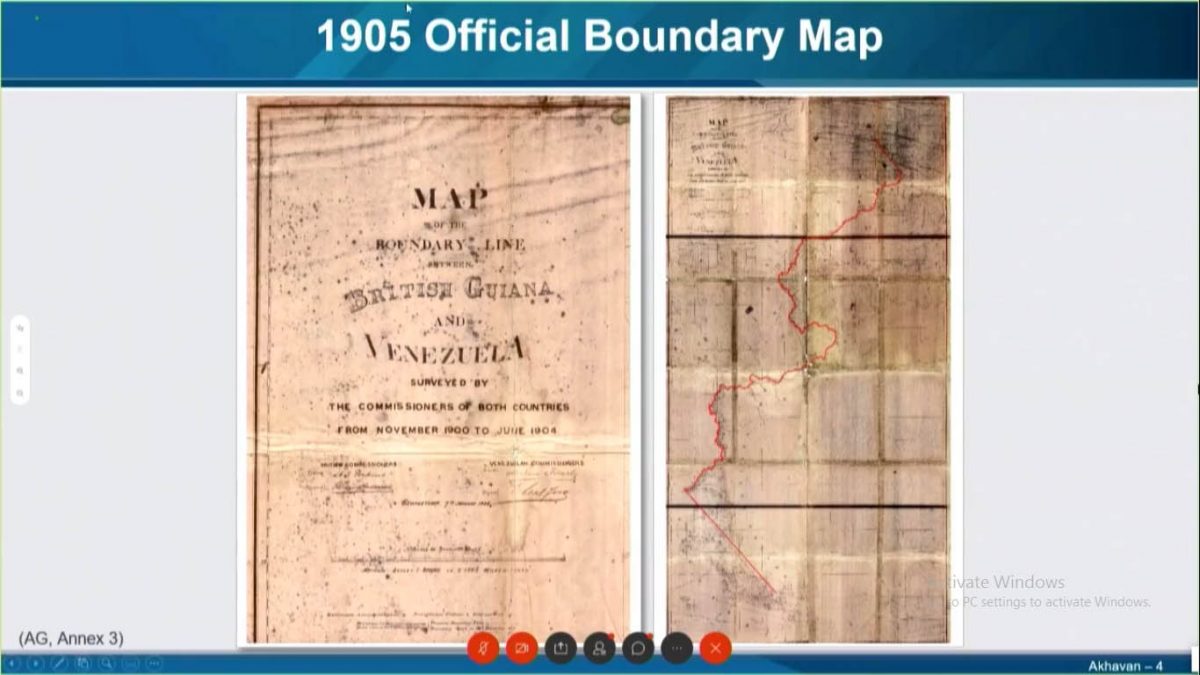

Following this award the two affected states in 1900 established a tribunal to mark the physical boundary with pillars and geographical features. This was completed in 1905 and a detailed map was published and endorsed by both Britain and Venezuela.

It was not until 1962, when the intention to grant Guyana independence received support from Communist nations at the United Nations, that Venezuela repudiated the agreement.

Since then, Venezuela has used a series of measures to try to intimidate Guyana and to prevent it from developing Essequibo and the waters offshore. Decades of the Good Offices facility under the UN Secretary General have also not yielded results.