Guyana’s enduring maritime heritage encompasses many celebrated personages and noteworthy events. Among the more memorable are the contributions of highly-skilled craftsmen who have long plied their boat-building trade on the Pomeroon River.

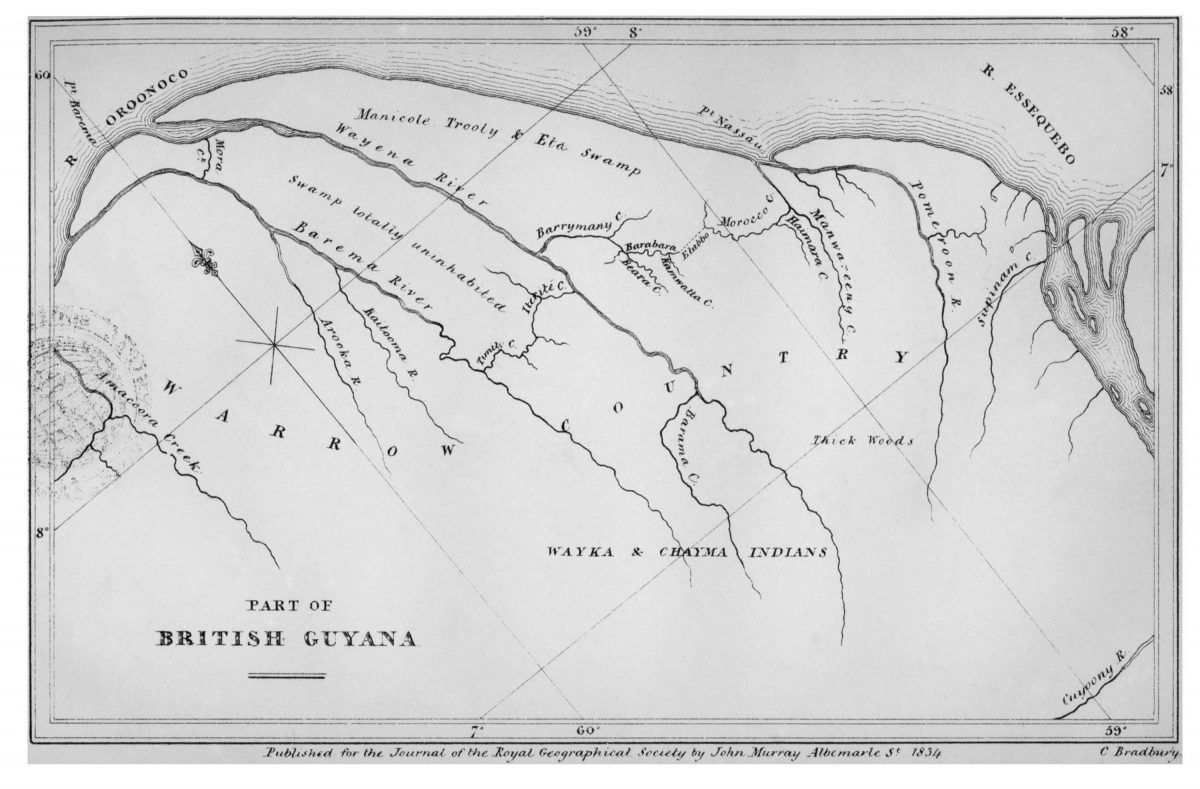

Boat-building began with the Warrau people of northwestern Guyana whose habitat once stretched from the Pomeroon coastlands across the Atlantic coast to the mouth of the Orinoco River.i At the arrival of Europeans in the 1580s, the Warrau comprised the largest tribal group in the area and historical documents describe “a nation of boat-builders” steeped in traditional knowledge of local timbers and construction techniques. In 1825, Land Surveyor and Quarter-Master General of Indians William Hilhouse, described Warrau boats as:

…constructed on the best model for speed, elegance, and safety, without line or compass, and without the least knowledge of hydrostatics; – they have neither joint nor seam, plug or nail and are an extraordinary specimen of untaught natural skill.ii

In 1841, Robert H. Schomburgk, Commissioner for Surveying and Marking out the Boundaries of British Guiana, attested:

The Warraus are famed for their skill in finishing canoes out of the single trunk of a tree. They formerly furnished the colonists, as well as the tribe of Indians inhabiting the coast regions, with canoes and corials which, for durability and speed, far surpassed any boats ever introduced from Europe. Of late years their industry has much relaxed, and they are loud in their complaints that the Spaniards of the Orinoko take away all their largest craft and destroy them, and that the smaller only escape by their being able to hide them. The famed Spanish launches, employed during the revolutionary war of Venezuela (1810-23) were made by the Warraus. Some of these were roomy enough for from 50 to 70 people. They refuse now to make any of so large a size, not for want of the trees fit for the purpose, but that, they say, if the Spaniards hear of their making any large craft, they send a party of men to take them away or cut them in pieces, in order to prevent them from being sold and used for smuggling by the people at the mouth of the Orinoco.iii

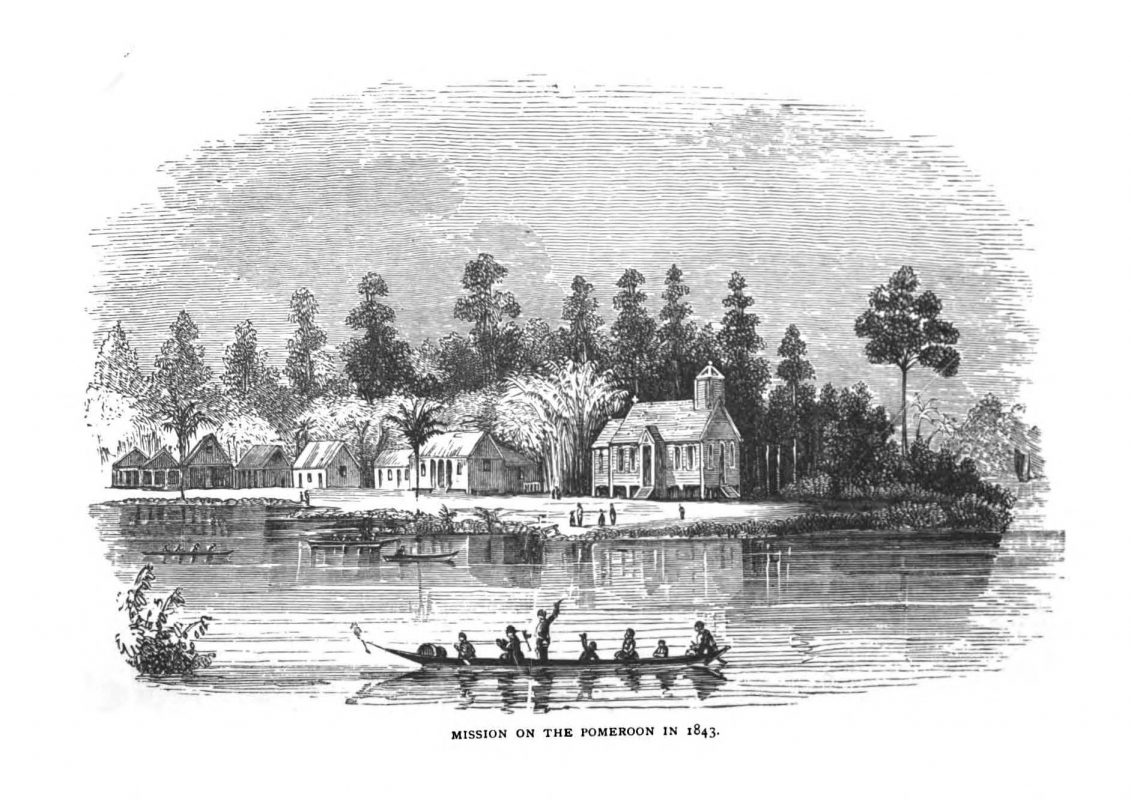

The suppression of Warrau boat-building by Spanish raiders early in the nineteenth century seems to have quashed the once-flourishing trade in the construction and sale of large boats in northwestern Guyana. The trade restarted after the arrival of formerly enslaved Africans and British, German, Madeiran-Portuguese, East Indian and Caribbean immigrants who settled and farmed the banks of the Pomeroon and nearby rivers from the 1830s. The resilient newcomers, called “grantholders”, likely contributed their knowledge of diverse construction techniques of former homelands, building on the legendary traditions of the indigenous Warrau who are, indisputably, the first ‘river-masters’ of northwestern Guyana.

Indigenous people in Guyana had harvested timber and troolie palm for their own use long before Europeans arrived. Boat-building timber – mainly Mora, Gale (Yellow), and Keriti (Keritee/Kretti) Siruaballi (Silverballi) and Greenheart – was sourced from the headwaters of the Pomeroon, felled by teams of woodcutters and floated downriver with the aid of bamboo rafts. Huge logs lay immersed in the River’s ‘water-sides’ (mudflats) for long periods of curing before being cut and dressed at nearby ‘saw-mills’.

Commercial woodcutting was underway and by 1833, Thomas Hubbard and Solomon Abrahams were partners in the firm George Garraway and Co., ‘Boat-builders and Carpenters in Pomeroon’. In 1834 George Frederick Pickersgill, ex-Justice of the Peace for North-West District, and James Chapman were operating a troolie and woodcutting business at the confluence of the Pomeroon and its tributary, the Arapiaco.v Another business, Alstein’s, was located upstream the Arapiaco and businesses owned by Holmes and Bunbury on the upper Pomeroon were also well-known.vi Up to the 1950s a large sawmill remained at Pickersgill, there was the Kamrudeen Sawmill on the Arapiaco, the Barakat

establishment at Jacklow and a mill at Charity co-owned by cousins Herman (‘Herbie’) Stoll and Alfred Van Sluytman.

Pomeroon boat-building ‘clans’ included the Brock menfolk: Charlie, Audley, Pelham, Sam, Sonny and Hubert; the Stoll brothers Alec, James, and Joseph with his son Fitzroy (‘Roy’) and nephew John Stanislaus; their cousin Milton Stoll and his sons Hector, Winston and ‘Binks’. The Adams boat-building family counted Joseph and his son Carl, as well as Joseph’s brother, John, and his sons Constantine (‘Connie’) and Patrick. Others specialists were Donald Younker, Victor Gamell Jr., Tony Gonsalves with sons Eric (‘Devil’) and Valentine (‘Pai’); Euclit and James Allen, Cecil and Emanuel De Agrella, Joshua (‘Joshi’) Fernandes, Tony Gouveia and Compton Correia-Cabose. The Pomeroon fraternity also included several skilled marine engineers who installed and serviced Kelvin and Petter inboard engines imported from the United Kingdom. Outstanding “engine-men” were Stanley (‘Piro’) Pires, Maloney Brown, Compton Gonsalves and Adrian Garraway.vii A few expatriates are remembered among the group. Barbadians, Captain Ira Sealy and an older brother journeyed to the Pomeroon around 1945 as sail-makers and consultants for the schooner Timothy A. H. Van Sluytman then under construction. A young St. Lucian, called “Ashe”, arrived on a local boat regularly transiting the Guyana-Caribbean shipping lanes during the 1960s and spent several months working at Joseph Stoll’s boatyard at Jacklow.viii

Joseph Charles Stoll (1901-1987) remains a legendary figure among Pomeroon’s illustrious brotherhood of master-builders. His German forebears had acquired land on the Pomeroon in the 1790s and had been slaveholders up to the early nineteenth century.ix Various Stolls had served as colonial government officials and interpreters for Warrau, Lokono/Arawak and Carib speakers in northwestern Guyana.x Significantly, colonial records list an Albertus Stoll, first as Postholder for Pomeroon then as a boat-builder in 1839 with several indigenous people in his household including John Simon “master boat-builder” and Daniel, a Warrau man.xi

Joseph – called ‘Skipper’, ‘Uncle Joe’ and ‘Kaiser’- ran a thriving boatyard at his Jacklow homestead employing as many as a dozen men at a time for large commissions. Between the 1930s and ‘70s, he and talented teams built and repaired hundreds of wooden schooners, sloops, fishing-boats, covered (tented) and open-air launches, and batteaux, ballahoos and small corials. By 1945, the carpenter turned master boat-builder had designed and delivered the largest wooden vessel ever built in Guyana up to that time. Commissioned by his cousins Basil and Ivy Stoll, the 76-ton, 120 foot-long Timothy A. H. Van Sluytman—named for Ivy’s father—was a stately two-masted schooner that relied on sails as well as inboard engines to power its regal hull across the Caribbean Sea. The Timothy Van entered merchant service transporting rice, timber, matches, diesel fuel, firewood and charcoal between Guyana, Barbados and Trinidad but its working life was curtailed following an initial engine-room fire during June 1952 while at berth in Georgetown. Chief Engineer Compton Gonsalves and Engineer, Adrian Garraway, suffered burns to their faces and hands and, after repairs, the historic vessel continued its inter-island service.xii Later that year, however, the schooner was destroyed while in port in Trinidad after a leaking oil drum triggered an explosion and fire onboard. Fortunately, the captain, crew and co-owner, Ivy Stoll – aboard for the voyage – all survived.xiii

Among Joseph Stoll’s many memorable commissions was the wooden cabin-cruiser Sarnia, built from a blueprint provided by Michael Adams, an Englishman employed with Sir William Halcrow & Partners, the British civil engineering firm rehabilitating the Tapacuma irrigation scheme in Essequibo during the 1960s. Stoll, who had been awarded a bursary in 1944 for Mold-Loft Work via ‘correspondence course’ from the Pennsylvania-based International Schools of Latin America, was reportedly the only builder able to follow the complex plans that Adams circulated among the boat-builders. Adams returned to England with his Pomeroon-built watercraft in tow.

Stoll and his able compères also built Verona, Perfection, Terrance S. and Anna Maria (for Basil and Ivy Stoll); Morn, Lady Vivian and Lady Frances (owned by Eric Stoll) and Melvern for Melba and Vernon Stoll. There was also Mañana built for Sydney Lawrie, Dwarka Ramcharran’s Malgretout and Reuben Stoby’s launches, Sir Reuben and Moruca Express. One of Stoby’s launches—likely Sir Reuben—is featured in Vincent Roth’s account of the British Guiana Legislative Council’s official tour of the North-West in March, 1952. Roth styled it “the largest sea-going launch in the district” by which Stoby trans-shipped merchandise brought from Georgetown on the Pomeroon ferryboat for his shop on the Moruka River adding:

It was a large roomy craft, roofed throughout its entire length with the forward portion converted into a comparatively comfortable cabin, behind which was the cargo-space and beyond that the powerful Kelvin engine.xiv

Roth’s account also highlights a perilous and costly but necessary manoeuver involving Stoby’s launch and the government-owned ferry service. Up to 1952, there was no public cargo vessel serving Moruka and communities nearby and, as the bi-weekly “Pomeroon steamer” did not make a scheduled stop until it was several miles upriver, Stoby was forced to rendezvous at the mouth of the river and hitch his sturdy launch to the ferryboat, unloading and transferring his cargo while being towed upstream.xv

Today, the distinctive river launches with their all-weather tents and accompanying ‘packa-packa’ engine sounds have all but disappeared as imported steel and fiberglass craft are preferred. Nevertheless, the Pomeroon’s boat-building heritage endures, albeit on a smaller scale, with the popular ‘speed-boat’ as the signature vessel.