In a unanimous decision giving itself jurisdiction, the Caribbean Court of Justice (CCJ) yesterday set aside the ruling of the Guyana Court of Appeal on valid votes and paved the way for GECOM to finally declare a result for the March 2nd general elections using the figures from the recount.

The court said it was also inconsistent with the constitution for the Chief Election Officer (CEO) or the Guyana Election Commission (GECOM) to disenfranchise thousands of electors in a seemingly non transparent and arbitrary manner, without the due processes established in Article 163 and the National Assembly Validity of Elections Act.

In fact, the apex court said that the local appellate court acted outside its ambit when it pronounced on the constitutional meaning of “votes cast” at the March 2nd polls.

The CCJ specifically noted that Eslyn David’s case did not fall within the scope of Article 177 (4) and therefore nullified the Court of Appeal’s majority ruling that the interpretation of the words “more votes are cast” catered for in Article 177 (2) (b) should mean “more valid votes are cast.”

In the circumstances the CCJ allowed the appeal taken before it by PPP General Secretary Bharrat Jagdeo and PPP/C presidential candidate Irfaan Ali.

In relation to a request made by counsel for the appellants, Justice Saunders said that the CCJ could not grant consequential orders, but specifically pronounced that the Court of Appeal’s decision be set aside for lack of jurisdiction noting that it was not final and therefore of no effect while also invalidating the June 23rd report issued by CEO Keith Lowenfield, discarding more than 115,000 votes which was based on that ruling. The invalidating of Lowenfield’s report is seen as a key opening for GECOM to proceed with the declaration of the recount result.

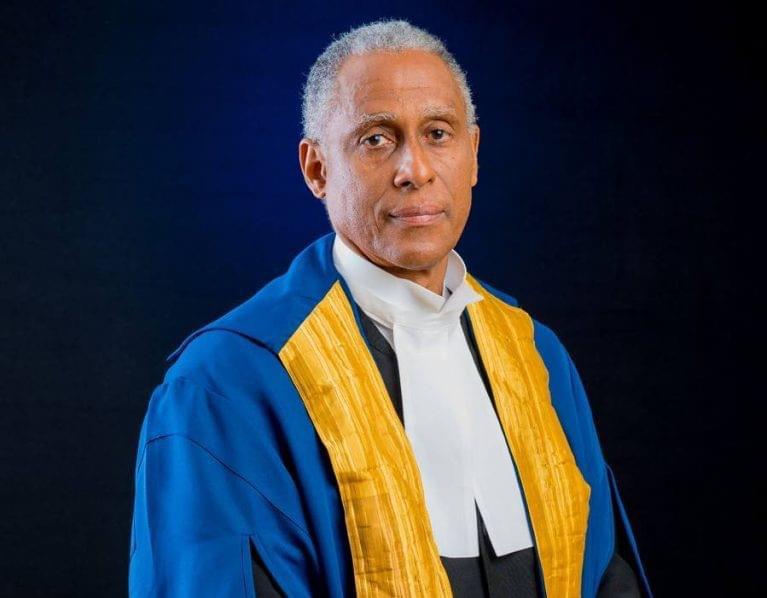

Ruling on the issue of its jurisdiction to hear the appeal, President of the CCJ Justice Adrian Saunders who read the judgment said that the court first recognized that Article 123 (4) of the constitution gives Parliament the power to make the CCJ the final court of appeal for Guyana.

Under that authority he said, the CCJ Act Cap 3:07 of the Laws of Guyana was enacted by which the CCJ was indeed made the final court of appeal for Guyana.

He noted that that CCJ Act has all the force of Guyana’s domestic law and it was that Act by which the question of the CCJ’s jurisdiction had to be guided.

The judge said the court determined that under the CCJ Act, its court has jurisdiction to entertain applications for special leave to appeal from any decision of the Court of Appeal in any civil matter.

Notwithstanding this power, however, he said that it had to be placed alongside Section 4 (3) of the CCJ Act which provides that the court has no jurisdiction to hear matters from the Court of Appeal which were declared to be final by any law.

Justice Saunders said the Court confirmed that Article 177 (4) is such a law but went on to state that the CCJ defined that Article as a “limited and circumscribed carve out” of the broad jurisdiction to grant a special leave application and to determine appeals from the Court of Appeal.

The judge said the court noted that Article 177 (4) is also “a carve out” of the exclusive jurisdiction over the validity of elections granted to the High Court by Article 163 of the constitution.

The CCJ held that Article 177 (4) should be strictly and narrowly construed.

The judge said there was no doubt that in instances where the Court of Appeal hears a question concerning the validity of an election of a president, where the question depends on that person’s qualifications or the interpretation of the constitution that such a decision would indeed be final and un-appealable to the CCJ.

The CCJ President reasoned that if no such question arose, however, or if the validity of the election did not depend on a question of the qualification of the person or, on the interpretation of the constitution, the Court of Appeal would not have jurisdiction under Article 177 (4).

He said that in such cases, any question about the validity of any elections must be referred to the High Court under Article 163 and that once the matter commenced in the High Court it was appealable (if necessary) right up to the CCJ as the final court of appeal.

It is this requirement which distinguished David’s challenge from what needed to be satisfied under Article 177 (4) and why her case was regarded to have fallen outside of this article.

The judge said that David’s attorney cited a number of authorities to suggest that the CCJ lacked jurisdiction to even entertain the appellants’ application for special leave to appeal, noting the court did not consider the authorities to be helpful.

Adherence to the constitution

On this point Justice Saunders said the CCJ recognised and re-affirmed its duty as Guyana’s final court of appeal to ensure adherence to the constitution. As such, in all the circumstances, and given the constitutional implications and public importance of the case, the judge said the Court granted special leave to Jagdeo and Ali.

Shifting attention next to the merits of the appeal, the CCJ President said that the Court looked at Guyana’s electoral system generally and also at Article 177 of the Constitution.

He said that Order 60 of the gazetted order which facilitated the recount of the ballots cast on March 2nd, “did not and could not affect the exclusive jurisdiction of the High Court under Article 163 to determine among other matters, any question in relation to whether an election had been lawfully conducted

He said that similarly affected was the National Validity of Elections Act which provides the method of questioning the validity of an election through the filing of an election petition which must be presented within 28 days of the publishing of the election results and that the High Court had the power even to order a fresh election in whole or in part.

The judge said that Article 163 provides a constitutionally mandated and evidence-based open justice process under the exclusive jurisdiction of the High Court, with the right of appeal, if necessary, to the Court of Appeal and ultimately to the CCJ.

Justice Saunders in the judgment said that the irregularities complained of by the incumbent APNU+AFC’s Joe Harmon which he (Harmon) contends were unearthed during the recount, and alluded to by Lowenfield are required to be addressed in an election petition.

On this point the judge said the Court held that Chairperson of GECOM, Justice Claudette Singh was right to state that GECOM lacked the legislative authority and the machinery to embark upon a determination of such irregularities.

In examining Article 177 which addressed the election of the president, Justice Saunders said that Article 177 (2) (b) provides that a person is deemed to be elected as President when “more votes are cast in favour of the list in which [that person] is designated as Presidential candidate than in favour of any other list.”

The court reasoned that the President is deemed to have been elected because, in the electoral process, an elector’s single ballot is really cast in favour of a list of candidates.

He clarified that there is now no separate election of a President as there used to be when Article 177 (4) was originally introduced as Article 30 (13) of the Constitution. He explained that in earlier times the President was elected by the votes of the members of the National Assembly, who had already been elected to that body but that that is no longer the case.

Article 177(4) he said, was always intended to operate after the President had been elected, originally by the National Assembly, or, as is now the case, when the President had been deemed and declared to be President after it was determined that more votes were cast in favour of the list in which he or she was designated as Presidential candidate than in favour of any other list.

Justice Saunders said that questions as to the validity of the President’s election were never intended specifically to impugn or relate to the validity of ballots cast by electors at the election of members of the National Assembly.

The CCJ was clear in pointing out that Article 177 (4) only affords jurisdiction to the Court of Appeal if the question raised as to the validity of an election of a President depends upon the qualification of any person for election or the interpretation of the Constitution.

Against this background the judge said it is evident from the nature of David’s complaints and the issues she placed before the Court of Appeal that the question(s) raised by her did not depend on the qualification of any person for election nor on the interpretation of the constitution.

David’s complaint, the court ruled, was really about the impact of Order 60 and the conduct of GECOM.

Justice Saunders said that what the Court of Appeal in its majority ruling did, was to embark upon an exercise of interpreting Order 60 and a consideration of the effect of that Order on the responsibilities of GECOM, while noting that in neither instance was there any need for an interpretation of any Article of the Constitution.

Article 177 (4) the CCJ ruled, “has always said what it meant and meant what it said.” The court then reasoned that there was therefore nothing in David’s application to trigger the Court of Appeal’s jurisdiction under Article 177 (4) while noting that the local appellate court therefore lacked jurisdiction to make the orders that were made.

Confined

The CCJ also made the observation that David’s attorneys suggested that the Court of Appeal had confined its jurisdiction to interpreting the words of Article 177(2) (b) “more votes are cast” in order to conclude that those words really meant “more valid votes are cast.”

It was argued that this brought their decision within the purview of Article 177(4). The Court said, however, that it did not accept that argument while declaring that the concept of “valid votes” is well known to the legislative framework governing the electoral process. The concept has a particular meaning in that context, the court said.

Justice Saunders pointed out that the phrase appears several times in the Representation of the People Act including at Section 96 which calls on the CEO to calculate the total number of valid votes of electors which have been cast for each list of candidates. “Validity in this context means, and could only mean, those votes that, ex facie, are valid,” the judge said.

He added that the determination of such validity is a transparent exercise that weeds out of the process, for example, spoilt or rejected ballots. The judge said that this is an exercise conducted in the presence of the duly appointed candidates and counting agents of contesting parties. It is after such invalid votes are weeded out that the remaining “valid” votes count towards a determination of not only the members of the National Assembly but, incidentally as well, the various listed Presidential candidates.

The court then went on to note that if the integrity of a ballot, or the manner in which a vote was procured, is questioned beyond this transparent validation exercise, say because of some fundamental irregularity such as those alleged by Harmon, then that would be a matter that must be pursued through Article 163 after the elections have been concluded.

The judge explained that at the point in the electoral process where Article 177(2)(b) is reached, there is no further need to reference “valid” votes because, subject to Article 163 (which is triggered by election petition after the election), the relevant validation process has already been completed. Unless and until an election court decides otherwise, the votes already counted by the recount process as valid votes are incapable of being declared invalid by any person or authority the CCJ ruling stated.

Justice Saunders said that by the unnecessary insertion of the word “valid”, the Court of Appeal impliedly invited Lowenfield to engage unilaterally in an unlawful validation exercise which trespassed on the exclusive jurisdiction of the High Court established by Article 163.

The judge noted on behalf of the Bench’s unanimous decision, that it was inconsistent with the constitutional framework for the CEO or GECOM “to disenfranchise thousands of electors in a seemingly non transparent and arbitrary manner, without the due processes established in Article 163 and the validation Act.”

The CCJ emphasised that the provisions of Article 177(4) were not triggered by David’s Application to the Court of Appeal and that the finality clause was inoperable.

Justice Saunders noted that it follows that, under the laws of Guyana, the CCJ did have jurisdiction to hear and determine Jagdeo and Ali’s appeal to set aside the decision of the Court of Appeal which he stressed had been made without jurisdiction. “It was therefore not final and is of no effect. This Court is entitled and required to declare it invalid and, likewise, the report issued by the Lowenfield which was based on it,” the apex court declared.

Raft

Justice Saunders said that while the Court was asked to make a raft of consequential orders relating to the Elections, it is important to bear in mind that the case before it was essentially about jurisdiction.

He then went on to say that once the Bench had decided that the Court of Appeal’s order was made without jurisdiction and should be set aside together with the CEO’s report that was based on it; there was nothing left upon which the CCJ would possess jurisdiction to make further orders.

The judge did say that as Guyana’s final court, “we cannot, however, pretend to be oblivious of events that have transpired since December 2018 (when the motion of no confidence was passed against the APNU+AFC government). Indeed, we have had to pronounce on some of those events.”

Noting that it has now been four months since the elections were held and the country without a Parliament for well over a year, the judge said that “no one in Guyana would regard this to be a satisfactory state of affairs. We express the fervent hope that there would quickly be a peaceable restoration of normalcy.”

The court noted that it is a matter of considerable concern for Guyanese that, although elections had been held as long ago as March 2nd the results had not been declared and the President and members of the National Assembly have not been appointed.

The CCJ observed that elections which are free and fair are the lifeblood of any true democracy and that all arms of state, whether legislative, judicial, or executive, are subject to the normative, enabling, and limiting jurisdictions, powers, and responsibilities that are constitutionally legitimate.

On this point Justice Saunders said that the Court is acutely conscious of the great importance of the proceedings and “our own ultimate responsibility to safeguard and uphold the provisions of the Constitution and the high constitutional values contained in the Preamble to that instrument.”

Justice Maureen Rajnauth-Lee Justice Denys Barrow Justice Peter Jamadar

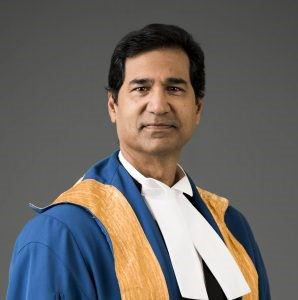

The case was presided over by Justice Saunders along with Justices Jacob Wit, Maureen Rajnauth-Lee, Denys Barrow and Peter Jamadar. The ruling was delivered virtually.

David had sought various orders against GECOM, including one restraining Lowenfield from submitting his final report, which the Chairperson of the Commission had instructed him to prepare in order to make a declaration of the final results of the March 2 polls.

The Court of Appeal on July 22 ruled that under Article 177 (4) the interpretation of the words “more votes are cast” catered for in Article 177 (2) (b) should mean “more valid votes are cast.” In that majority decision the Court of Appeal found that under Article 177 (4) of the Constitution, it had the jurisdiction to pronounce on David’s application, which sought to restrict the final declaration of the results to only votes deemed valid by Lowenfield.

The court found that the words “more votes cast” should be interpreted to mean “more valid votes are cast” in relation to the elections held on 2nd March 2020.

Since that ruling Lowenfield has submitted a report in which he controversially removed over 115,000 votes, using the Court of Appeal ruling as the basis for the exclusion.

Jagdeo and Ali were represented by a battery of attorneys led by Trinidadian Senior Counsel Douglas Mendes while David was represented also by a battery of lawyers which was led by Senior Counsel John Jeremie.