Not wanting to deny, I

believed it. Not wanting

to believe it. I denied

our Bastille Day. This,

is nothing to storm. This

fourteenth of July. With

my own eyes I saw the fierce

criminal passing for citizen

with a weapon, a piece of wood

and five for one. We laugh

Bastille laughter. These are

not men of death. A pot

of rice is their foul reward.

I have at last started

to understand the origin

of our vileness, and being

unable to deny it, I suggest

its nativity.

In the shame of knowledge

of our vileness, we shall fight.

Martin Carter

After One Year

[. . .]

But in your secret gables real bats fly

mocking great dreams that give the soul no peace,

and everywhere wrong deeds are being done.

Rude citizen! Think you I do not know

that love is stammered, hate is shouted out

in every human city of this world?

Men murder men, as men must murder men

To build their shining governments of the damned.

Martin Carter

July 14 is Bastille Day, celebrated with much pageantry and ceremony in France and known throughout the world. It has a particular place in history because of its significance to political dictatorship, tyrannical rule as well as revolution and liberation. For the French, it is the anniversary of the overthrow of a long period of absolute monarchy.

It is also a significant day in Guyana as it is the anniversary of the murder in broad daylight of Roman Catholic priest Fr Bernard Darke in 1979, against a background of struggle in the face of oppressive politics and rigged elections. It is the anniversary of massive public demonstrations on the streets of Georgetown against a government who kept a stranglehold on power through fraudulent elections and a reign of terror against political opponents.

Bastille Day in Paris is the anniversary of “the storming of the Bastille” on July 14, 1789, which helped usher in the French Revolution. This history may be dated back to the reign of an absolute monarch, Louis XIV known as “Le Roi Soleil” (the Sun King). Louis XIV set off a long period of absolute monarchy in France and is (in)famous for his arrogant statement “L’etat c’est moi” (I am the state) which characterised the French government right up to Louis XVI who was on the throne when the French Revolution broke out.

The Bastille was a prison in Paris kept by these kings for the holding of political prisoners. The revolutionary fever had been heating up, led by the Jacobins, and driven by the slogan “liberte, egalite, fraternite”. On July 14, 1789 it erupted when a large mob of people “stormed the Bastille” – they marched to the prison, charged the barricades, and set all the victims free. A reign of terror followed.

In 2010 Fr Malcolm Rodrigues SJ, wrote an account of Guyana’s Bastille Day. Fr Rodrigues summarised the history of that period in Guyana and the consistent position taken by the Roman Catholic church in support of democracy, human rights, and freedom of expression. The church incurred the wrath of the governing party, which stayed in power through rigged elections and stifling of dissent.

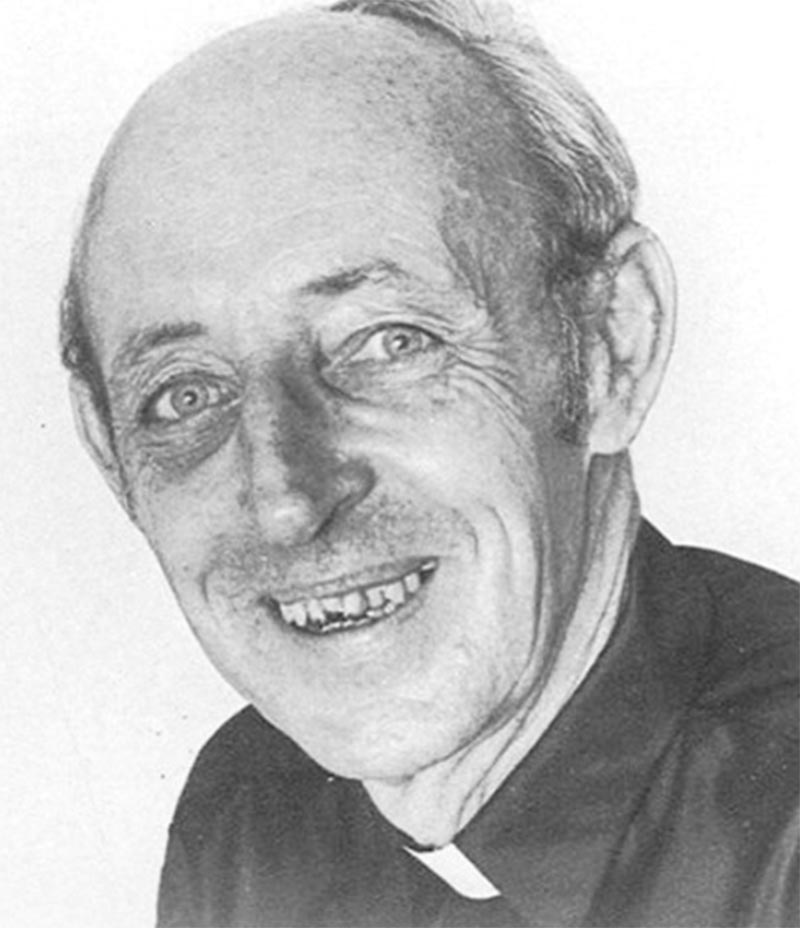

Jesuit priest Fr Bernard Darke arrived in Guyana in 1960 and was serving as a teacher at St Stanislaus College in the 1970s. He was also well known for his work as a photographer and served in that capacity with the Catholic Standard newspaper. Popular sentiment against the PNC government was growing and was seriously escalating after the fraudulent Referendum in 1978. Protest was building up led by Walter Rodney and his WPA, and the PPP. In July 1979, there was a massive street demonstration and Fr Darke was at work on the premises of St Stanislaus when he decided to get some pictures of the protest for the Catholic Standard. He became an immediate target for armed thugs hostile to the demonstration. He was pounced upon and in a struggle to secure his camera and in defence of democracy, knifed to death.

Poet Martin Carter, who himself had joined the protest, expressed his profound shock in the poem “Bastille Day – Georgetown”. He compares the incident to the French Revolution but told the story of how he came to affix that title to the poem about Fr Darke’s murder. As was his wont, he was engaged with a small group in a discussion on politics and poetics in a rum shop in South Georgetown. A well-known associate of his, Ivan Forrester, popularly known as Farro, stopped in, and heard members of the company weighing in on the sins of the government. Farro threw out the question, “then when shall we storm the Bastille?”

It was easy, if not natural, for Carter’s poetic mind to get to work on the significant links between the French Revolution and the rising situation in Guyana. The cruel coincidence of the popular protest taking place on, of all days, the anniversary of the storming of the Bastille.

Fr Rodrigues’s analysis of the killing of the priest took into consideration the hostility of the government to the Jesuits, which filtered down to their supporters and to the thugs who were in the habit of attacking members of the political opposition. Carter refers to them in the poem, and Fr Rodrigues analyses the deep-rooted political pollution within the society just as the poet sees the murder by minions as a stunning revelation of “the origin of our vileness”, the unbelievable depths into which the society has collapsed.

That vile origin lingered. This much is expressed by Carter in the second poem “After One Year”. The poet owns the “vileness”, the murderous malevolence settled in the nature of man, the nature of human society. He refers to it as a cycle and a force that has damned the Guyanese society.

On Bastille Day the French overthrew their tyrannical forces. Today they celebrate July 14 as a day of liberation. Guyana remembers the day as the date of a popular rising against similar forces. But more than that, it is a reminder that liberation did not take place in 1979. Guyana’s tyrannical force never really went away and has returned like a cycle of history with the persistent threats against democracy in Guyana in 2020.