The 2016 Production Sharing Agreement (PSA) with ExxonMobil’s subsidiary, Esso Exploration and Production Guyana Limited (EEPGL), gave the company generous terms of relinquishment for the massive Stabroek Block that would see it holding on to key acreages until 2023 and costing the country billions of dollars, according to attorney-at-law and civil society activist Christopher Ram.

As he blasted de facto Minister of Natural Resources (MoNR) Raphael Trotman, whose ministry led negotiations and who signed the 2016 agreement, Ram says this country would have been better off keeping the old 1999 PSA as it provides for the most beneficial relinquishment terms when compared to both a 2012 contract template created by the Guyana Geology and Mines Commission (GGMC) and the agreement signed by the APNU+AFC government in 2016.

“Had Trotman not been so reckless, irresponsible or just plain ignorant of the petroleum laws and practices, by the time the fourth anniversary came around on June 27, 2020, Guyana would have been able to recover thousands of square miles of de-risked oil blocks worth billions of US dollars, at recent international auction prices,” Ram, credited for first making public that government had received a secret US$18 million signing bonus on the new PSA, told the Sunday Stabroek.

“But Trotman did not even bother with anniversary dates, opting instead for the uncertain concept known as effective date, and defined as the date on which the Petroleum Prospecting Licence came `into full force and effect’. Trotman seemed to `negotiate’ blind to the fact that Esso/Exxon had been in Guyana for sixteen years plus when the 2016 Agreement was signed. It was it seems that Exxon got what Exxon wanted, and more,” he added.

However, the company argues that the 2016 agreement has allowed it to maximize the potential of the area by allowing for state-of-the-art exploration and thus creating value for this country.

“ExxonMobil Guyana is committed to exploring and developing Guyana’s oil and gas resources in a responsible and mutually beneficial way. The 2016 petroleum agreement has allowed us to create tremendous value for Guyana through continued exploration and appraisal, including evaluation of the largest 3D seismic campaign undertaken by ExxonMobil at that time, which successfully led to development of the Liza projects on the Stabroek Block,” Public and Government Affairs official Deedra Moe told this newspaper.

“We have complied with all relinquishment requirements on the Stabroek Block and are scheduled to relinquish additional acreage in 2023 after completion of the first renewal period, as outlined in the 2016 petroleum agreement,” she added.

The Sunday Stabroek reached out to Trotman for comment and he said, “All matters relating to petroleum should be referred to the Department of Energy of the Ministry of the Presidency.”

A Cabinet-sanctioned review of the circumstances leading to the signing of a new PSA with the company in 2016 concluded that while the agreement was negotiated and executed in accordance with the law, a lot of pressure was placed on government for a speedy signing prior to the scale of the “world class” Liza-2 discovery becoming fully known and understood.

“Overall, the 2016 Agreement contained some improvements in comparison with the 1999 Agree-ment. The Contractor Con-sortium was not receptive to any changes and fought hard to retain the same terms as in the 1999 Agreement. There were also changes that were of benefit to the Contractor Consortium,” the review, undertaken by the United Kingdom-based law firm Clyde and Company and paid for by the Govern-ment of Guyana, stated. The Contractor Consor-tium refers to EEGPL, Hess Guyana Exploration Ltd and CNOOC Nexen Petroleum Guyana Limited, the partners in the 26,800 square kilometres Stabroek Block.

“The Contractor Con-sortium appears to have put a lot of pressure on the Government and the MoNR to secure the 2016 Agreement in a short time scale,” said the report, dated 30 January 2020.

‘Generosity’

But comparing relinquishment terms of the 1999 contract with EEPGL and Government, the 2012 template created by the GGMC and the 2016 Agreement, Ram contends that but for the very generous clause in the Petroleum Agreement signed by Trotman, Guyana would have seen the return of some of the millions of hectares (thousands of square miles) from ExxonMobil on the anniversary date of the Agreement this year.

He said that ever since Guyana introduced petroleum legislation in 1987, the law has set out a regime for the allocation of petroleum blocks to oil companies and their periodic, incremental relinquishments by those companies. The Petroleum Exploration and Produc-tion Act contemplates two types of licences – an Exploration Licence and a Production Licence.

An Exploration Licence lasts for ten years beginning with an initial period of four years with an additional six months as a preparation period. Thereafter, at the option of the licencee there are two renewal periods of three years each.

“When Trotman entered into the 2016 Petroleum Agreement with Esso and the two other oil companies Hess and CNOOC/ Nexen, he could have drawn on three models: the law itself, the Agreement signed by then President Janet Jagan with Esso as a single entity in 1999 and a Model Agreement published by the GGMC in 2012. Janet Jagan came in for severe criticism for the significant acreage granted under the 1999 Agreement but those defending the generosity pointed out that an oil discovery was a long shot with little prospect of success. Despite that situation, the Agreement had the most aggressive relinquishment provision, more than the law itself, the 2012 Model and worst of all, Trotman’s post-discovery Agreement,” Ram said.

He pointed to criticisms of the massive acreage accorded to Esso in the 1999 agreement when the law provided for a maximum sixty blocks.

That norm can be exceeded under special circumstances. So that instead of the area being 2,300 square miles, the actual area granted was 10,350 square miles, or one-twelfth the size of Guyana.

But sources both in the Janet Janet administration and others familiar with the agreement said that when she awarded 600 offshore blocks to EEPGL in 1999, a key factor was the then government’s interest in attracting big name American investors who would help fend off Venezuela’s decades-old claim to the Essequibo region.

Moves in this regard date back to the late 1990’s, when Guyana had hoped to attract Beal Aerospace to launch satellites from the Waini area in the North West but the biggest breakthrough, however, came in 1999, when Jagan inked a PSA with ExxonMobil’s subsidiary EEPGL.

The deal with Exxon coincided with having United States-based Beal Aerospace also anchor in the Essequibo region since this country was seeking economic and strategic alliances.

Government had invited Beal here the same year and on the day of the EEPGL signing, a team from Beal flew into Guyana for a promotional campaign and to start negotiations on setting up of a launch site in Region One.

Venezuela would later object to the site of the proposed satellite operation, contending that the Waini was part of its “reclamation zone.”

The negotiations with Esso and Beal ran simultaneously and while the Esso agreement was signed on June 14th, 1999, Caracas would one week later object to the proposed aerospace site.

“We have an objection to the intention of mounting the aerospace base in the territory of reclamation,” Jose Vicente Rangel, then Venezuelan Foreign Minister, was reported as saying by the Venezuela Newspaper El Nacional. Beal eventually gave up its quest.

According to a statement from the Guyana Geology and Mines Commission (GGMC), following the signing of the 2016 Esso PSA, “the agreement is similar to other current agreements” and was based on a proposal to the GGMC for a PSA in respect of petroleum acreage offshore.

The statement made no mention of the number of blocks but said that the contract was for 60,000 square kilometers of deep-water space, commencing 120 kilometers from the coast line. It added that it was based on the provisions of the mining policy that the government adopted in January of 1997. That policy provided for compliance with the provisions of the Petroleum Act and Environmental Protection Act of Guyana.

It also said that available acreage from adjacent areas near shore were studied but only pioneering work would reveal whether there are favourable prospects for commercial reserves of natural gas or petroleum.

On May 15th, 2015, ExxonMobil and subsidiaries announced what would be the first of several oil finds in the Stabroek Block offshore Guyana.

In 2016, when government renegotiated the contract with ExxonMobil, it did not address the issue of the 600 blocks and in this respect left the PSA as it was in 1999. Government has defended its actions in not reclaiming the areas, saying that it was strategic then and remains the same.

‘Clouded’

Ram said that the 2015 oil discovery by ExxonMobil was evidence to government that it should leave the relinquishment terms of the contract alone or even use it as leverage to secure overall better terms of the agreement.

“Despite having at his disposal the benefit of seventeen years and direct information of a world class discovery in the area, Trotman not only allowed the same area in a new Agreement, but treated Exxon as if it was new to Guyana and allowed the company to recover all expenditure it claimed to have incurred under the 1999 Agreement! It keeps getting worse for Guyana. The entirety of that Agreement seems clouded in illegality since an oil company is only entitled to a single Agreement and ExxonMobil had fully run out its first Agreement, including a period of force majeure,” Ram said.

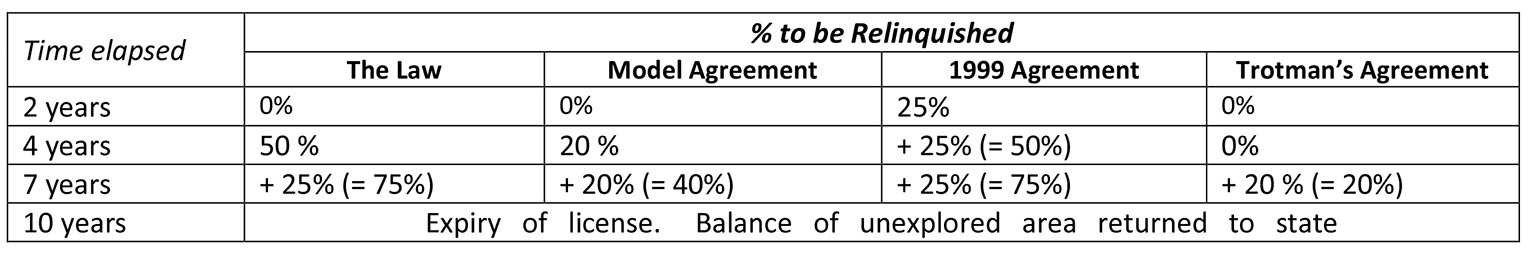

“Very importantly and costly for Guyana, Trotman stripped the 1999 Agreement of its robust relinquishment provision. Under the 1999 Agreement, Esso was required to give up, cumulatively, 25% after two years, 50% after four years and 75% after seven years. Similarly, Ratio Guyana Limited with which then President Donald Ramotar signed an Agreement shortly before the May 2015 elections had almost identically robust relinquishment provision except that after seven years the area to be relinquished is 65%. By comparison, while the Act has no two-year relinquishment requirement, 75% of the contract area would still have to be given up after seven years into an exploration licence. Finally for purposes of benchmarking, the 2012 Model Agreement requires the cumulative relinquishment of 20% after four years and 40% after seven years,” he said.

“Compare these with Trotman’s post-discovery Esso agreement which allows the licencees to hold on to 100% of the oil blocks for a full seven years and to 80% for the entirety of the ten years duration of the Prospecting Licence. Having carried out exploration activities for a full seven years on their Block, it is unlikely that the 20% to be relinquished will have any real or potential value to any other oil company, especially if these do not constitute contiguous blocks. By contrast, had the 1999 provision been retained, after two years the State would have seen the return of 2,600 square miles and a similar amount after a further two years. In the eighth year all Esso would have had control of would have been 2,600 square miles plus those retained under a Production Licence. Under Trotman’s 2016 Agreement, in the eighth year, Esso would still be controlling over 8,200 square miles plus all areas retained under Production Licence,” he added.

Using the table below, he stressed that if government had not changed the terms of relinquishment, it would have still been able to regain valued acreage and could have auctioned those off for large sums, since the basin is a global oil investment magnet.

10 years Expiry of license. Balance of unexplored area returned to state“There is no act in the history of this country, including by the French or the Dutch in the pre-British Guyana or the Bookers era that equals the blind cession of the resources and wealth of this country to match what Trotman has done. The consequence is immeasurable, irreparable and practically infinite,” Ram said.

10 years Expiry of license. Balance of unexplored area returned to state“There is no act in the history of this country, including by the French or the Dutch in the pre-British Guyana or the Bookers era that equals the blind cession of the resources and wealth of this country to match what Trotman has done. The consequence is immeasurable, irreparable and practically infinite,” Ram said.