LONDON, (Reuters) – An experimental vaccine being developed by AstraZeneca and Oxford University against the new coronavirus produced an immune response in early-stage clinical trials, data showed yesterday, preserving hopes it could be in use by the end of the year.

The vaccine, called AZD1222, has been described by the World Health Organization’s chief scientist as the leading candidate in a global race to halt a pandemic that has killed more than 600,000 people.

More than 150 possible vaccines are in various stages of development, and U.S. drugmaker Pfizer and China’s CanSino Biologics also reported positive responses for their candidates on Monday.

The vaccine from AstraZeneca and Britain’s University of Oxford prompted no serious side effects and elicited antibody and T-cell immune responses, according to trial results published in The Lancet medical journal, with the strongest response seen in people who received two doses.

British Prime Minister Boris Johnson, whose government has helped fund the project, hailed the results as “very positive news” though the researchers cautioned the project was still at an early stage.

“There is still much work to be done before we can confirm if our vaccine will help manage the COVID-19 pandemic,” vaccine developer Sarah Gilbert said. “We still do not know how strong an immune response we need to provoke to effectively protect against SARS-CoV-2 infection.”

AstraZeneca shares surged 10%, but then gave up most of those gains, to close up 1.45% on the day.

AstraZeneca has signed agreements with governments around the world to supply the vaccine should it prove effective and gain regulatory approval. It has said it will not seek to profit from the vaccine during the pandemic.

AZD1222 was developed by Oxford and licensed to AstraZeneca, which has put it into large-scale, late-stage trials to test its efficacy. It has signed deals to produce and supply over 2 billion doses of the shot, with 300 million doses earmarked for the United States.

Pascal Soriot, Chief Executive of AstraZeneca, said the company was on track to be producing doses by September, but that hopes that it will be available this year hinged on how quickly late-stage trials could be completed, given the dwindling prevalence of the virus in Britain.

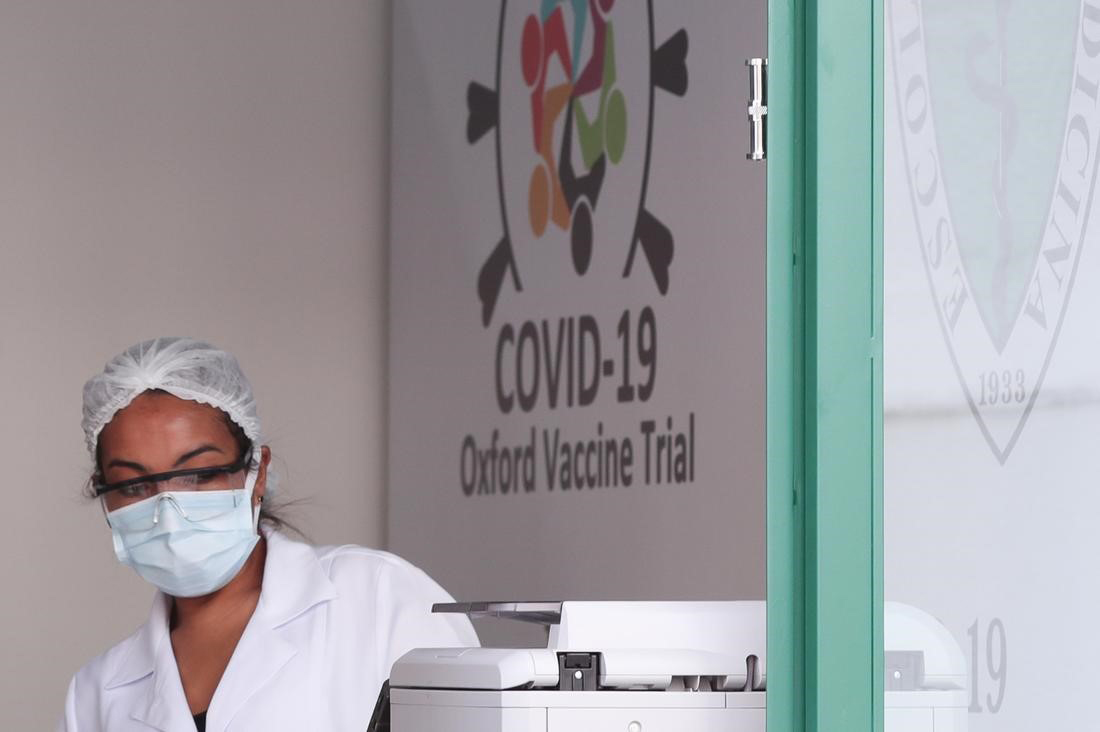

Late-stage trials are under way in Brazil and South Africa and are due to start in the United States, where prevalence is higher.

The trial results showed a stronger immune response in 10 people given an extra dose of the vaccine after 28 days, echoing a trial in pigs.

Oxford’s Gilbert said the early-stage trial could not determine whether one or two doses would be needed to provide immunity.

“It may be that we don’t need two doses, but we want to know what we can achieve,” she told reporters.

AstraZeneca’s biopharma chief, Mene Pangalos, said the firm was leaning towards a two-dose strategy for later-stage trials, and did not want to risk a single or lower dose that might not work. The antibody levels generated were “in the region” of those seen in convalescent patients, he said.

The trial included 1,077 healthy adults aged 18-55 years with no history of COVID-19. Researchers said the vaccine caused minor side effects more frequently than a control group, but some of these could be reduced by taking the painkiller paracetamol, which is also known as acetaminophen.