BUENOS AIRES, (Thomson Reuters Foundation) – Argentina plans to put into orbit a satellite with new precision technology in the coming days, to monitor felling of its native forests round the clock and accurately measure forest carbon stocks in a bid to help curb climate change, scientists said.

The SAOCOM 1B satellite, manufactured in the South American country, is due to be launched between July 25 and 30 from Cape Canaveral in Florida, managed by experts from Argentina’s National Commission for Space Activities (CONAE).

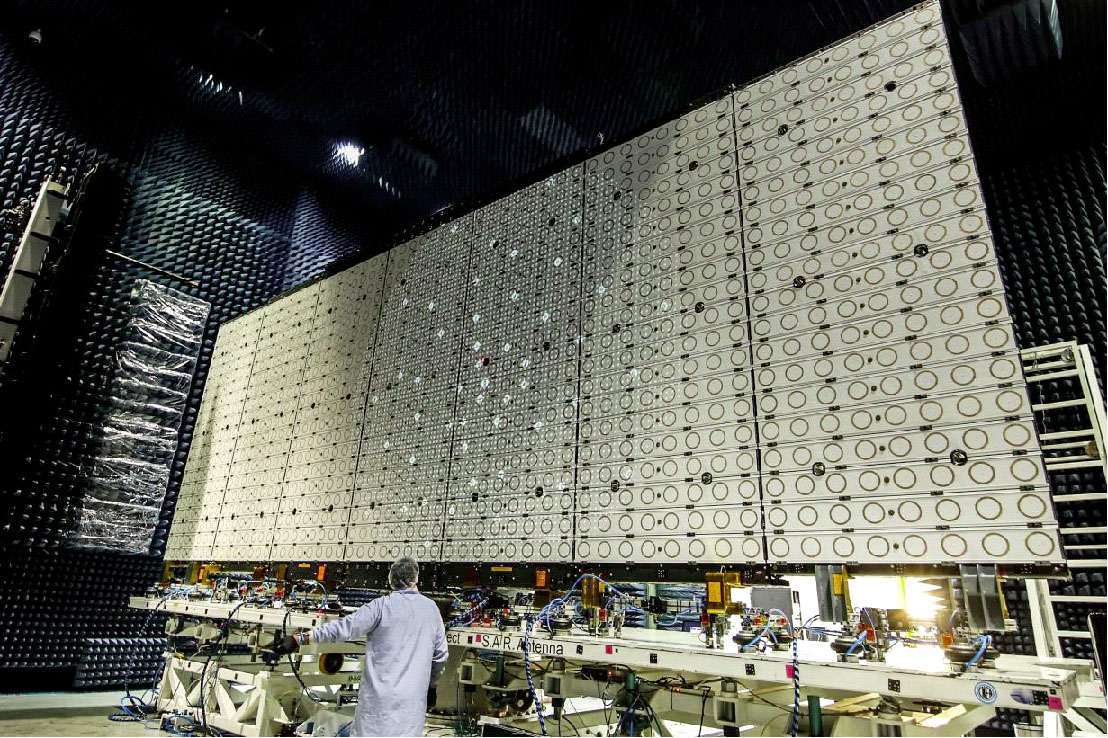

The satellite, equipped with the latest technology, represents a huge leap from those that use optical sensors.

SAOCOM 1B’s main Earth observation instrument is a radar that works with microwaves in the electromagnetic L-band space, providing information 24/7 about what it can see: soil moisture, crops, forest structure and changes in glaciers.

“There is only one similar satellite developed by the Japanese space agency,” Laura Frulla, head of research for the SAOCOM mission, told the Thomson Reuters Foundation.

“It’s a very important advance because optical sensors work with sunlight, but microwaves go through clouds, work in rain and don’t need light,” she added.

The new development comes at a key moment.

“Argentina is not only in a health emergency due to COVID-19 but also in a forestry and climate emergency,” warned Hernán Giardini, coordinator of Greenpeace’s forests campaign in Argentina.

A U.N. report published in 2015 identified Argentina as one of the 10 most deforested countries in the world. Between 1990 and 2015, it lost forests equivalent to the size of Scotland.

The decline in forest cover has since slowed but continues, the U.N. Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) said this year.

Official figures from the Argentinian government show 182,000 hectares were deforested in 2018 – about half in protected areas – down from 350,000 hectares in 2012.

But in the first half of 2020, with coronavirus restrictions since March making it harder to enforce protection, Argentina lost more forest than in the same period last year, according to Greenpeace, which tracks optical satellite images.

“Just during the quarantine, 21,000 hectares were deforested – an area equivalent to the city of Buenos Aires,” Giardini told the Congressional Natural Resources Commission this month.

The critical area is the Gran Chaco, a wide South American tropical and subtropical region which includes four northern provinces of Argentina: Formosa, Chaco, Salta and Santiago del Estero.

That area, which captures 50% of the carbon stored in the country’s forests, is also where 80% of clearance takes place.

The main causes of deforestation are expansion of soybean cultivation and intensive livestock breeding, as well as forest fires. The Chaco forests are cut down to plant pasture and raise livestock for meat exports to China and the European Union.

In Argentina, the greatest deforestation occurs in the tropical area of Gran Chaco, where dense clouds are common, said Pablo Mércuri of the National Agricultural Technology Institute.

“With more information from this region we will be able to track native forests much better,” he said.

“The optical satellites used today do not capture images on cloudy days or at night, but the new ones allow you to traverse the clouds and operate both day and night,” he explained.

SAOCOM 1B will be complemented by SAOCOM 1A, put into orbit in 2018, which provides some images but is still “in the process of calibration”, Mércuri said.

The two will form a constellation that will provide greater variety and frequency of data, in conjunction with satellites from other countries that use similar X-band microwave technology but cannot penetrate forest cover.

SAOCOM’s Frulla said the new system will be useful because it allows monitoring of changes in both planted and native forest that look different. Three hours after logging or a fire, the affected area can be measured and its recovery observed.

Unlike optical satellites which only provide estimates, the new system will accurately measure biomass, whether it is dry or wet, the tree type, undergrowth and humidity levels, she said.

The satellites can also be used to detect areas at risk of fires, floods and crop diseases, allowing for early warning.

The L-band radar technology, which penetrates the surface, is dominated by Argentina and Japan, and may be sold to other countries as the satellites observe the whole of the Earth, passing twice a day at the same point, she noted.

Mércuri said radar satellites can capture the density of a forest and different structures within it.

To raise awareness of the importance of using forests sustainably, more and better data like this needs to be produced, he noted.

“Native forests are not even – they are very thinned by deforestation and in some areas inaccessible,” he said.

The satellite information will make it possible to identify forest areas that should remain pristine, he added.

The system will also help quantify carbon stocks in the forest and soil, and certify them.

This process is important to verify carbon credits that can be purchased to offset greenhouse gas emissions elsewhere.

“This technology will allow us to make high-precision inventories at the sites of greatest interest,” Mércuri added.