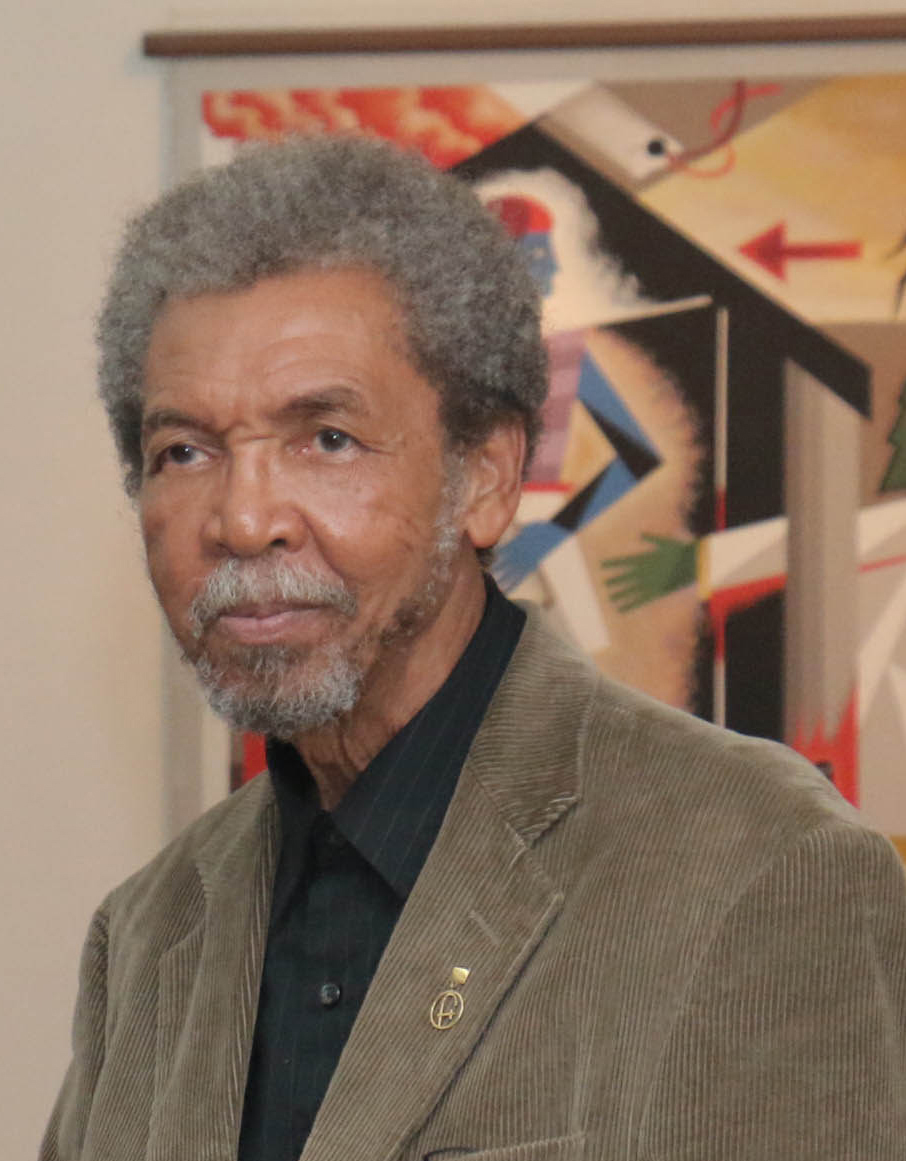

By Stanley Greaves

The Compact Oxford dictionary states that art is “The expression of creative skill in a visual form such as painting and sculpture”. The philosopher and critic Susanne Langer writes, “Art is the creation of perceptible forms expressive of human feelings,” which expressions, I would add, can be found in any culture. The combined statements best suit what is about to be expressed. One also has to bear in mind that a culture encompasses everything that takes place in any community great or small. What must be considered are existing conditions that not only allow such expressions to exist but to support the activity as well.

My first meeting with George Simon took place in the late 1970s, when he visited my home. He introduced himself as studying printmaking in the UK. I was surprised to see a young person of Indigenous origin studying art in the UK. I knew of artist Marjorie Broodhagen and ceramist Stephanie Correia having a similar Indigenous background, but only Broodhagen had studied abroad. George explained that he was in his final year and was having problems about the kind of themes he wanted to explore, with the biggest problem being how such expressions would be received. I had faced the similar problem myself in the UK—thinking of themes to paint. This was resolved when Murray McCheyne, the tutor, suggested sculpture.

My exploration in forms were understood. I told George that he would have to find a way around the problem of cultural gaps. I mentioned my experiences in the hinterland and efforts to establish a spiritual connection with Guyana as a means of removing foreign influences. For me, the obvious thing was to investigate Indigenous symbols. After three paintings in 1954, realising they held no significance for anyone, I stopped. Such investigations, I felt, were the province of an Indigenous artist and George’s symbolic paintings later proved the point.

I first met Osaze, a name he gave himself, when he was in a group of young artists I was asked to tutor in the art of book illustration. The request came from Agnes Jones, of the Ministry of Education, who at the time was in charge of the publication of readers for Primary Schools, a pioneering venture not attempted anywhere else in the Anglo Caribbean. Being the Art Master at Queen’s College and having access to the Art Room, I conducted classes there on Saturday afternoons. Osaze turned out to be a talented draughtsman and of a very humorous disposition. During classes he would make remarks based on his perceptions before convulsing into laughter. This disposition was well reflected in his commendable drawings. There was no doubt that he had a firm connection with his interior self, something which remained to the end of his life. He became a student at the Burrowes School of Art at the same time George returned to begin teaching printmaking. Osaze, unfortunately, did not graduate because he had no financial support and had to find work.

Being from a working class background, he found existence difficult. Osaze once described to me a rice and meat lunch where meat was fried ochroes, but could have been eddoe leaves from nearby. Freddie Kissoon relates having “coffee” at Osaze that was made from parched rice-grains. I discovered Osaze was trying to understand and establish the foundation of his spirituality based on studying the Bible. He also connected to his African heritage, becoming expert at African forms of drumming practised in Guyana. At this point, it is important to note that while George’s culture existed in Guyana and could provide a firm foundation, Osaze felt his was in West Africa and he had to be content with racial memory. He eventually worked for the WPA and for a while did not find time to practise for any form of artwork. George, on the other hand, because of his occupation, did find the time to do so.

George began to establish himself as an artist after his first encounter with the Wai-Wai community in the South Rupununi. He did a series of large drawings which, at my suggestion, were first exhibited by the Dorothy Taitt foundation at what is now Cara Lodge. It was interesting to witness from this encounter the speed at which George reconnected with his culture that involved both natural and spiritual environments. His work gravitated from realism to powerful depictions of symbolic and mythical aspects of Indigenous Culture. Living in the city did allow him to exhibit work and to be recognised as an artist. Having studied European art forms, George was able to make use of his training in a remarkably effective way. In making prints by etching, the ink is wiped off the plate leaving a residue in etched lines to produce the print. George began to put paint on the canvas and then wipe off parts in a particular manner leaving thin films remaining. It was a form of glazing but he used his hand in a way that allowed variations of thickness of paint to remain.

Unlike George, Osaze had no direct contact with European values in the practice of art that conditioned his approach to his work and in any case he was not interested in following the dictates of style but did proceed to paint his visions in any style he thought would best accommodate his ideas. George was disciplined in his approach and one could follow the stylistic lines of development in contrast to Osaze, who employed whatever approach as the spirit moved him. There was a time when artists’ paints were not available in the country and Osaze used whatever he could find to continue working, for example, coconut shells, bits of mirror, buttons, seeds, cloth to construct a remarkable series of masklike forms. The individuality and power of each piece was unquestionable. You felt a soul was in residence and according to the configuration of the work you had to decide whether you could live with it or not. Some pieces could well have been used in the practice of obeah. I personally felt the masks were evidence of his spiritual connection to Africa.

Speaking about the spirit, there were a couple of times in Barbados I was present at an exhibition of George’s work (and those of his brother Ossie the sculptor) when dressed in white he introduced himself to viewers as a shaman. Perhaps the point being made was that there was something mystical about his work in which case it should be revealed by the work itself, as did happen in later years.

While George exhibited work in the Caribbean and internationally, Osaze was disinclined to take part in exhibitions. From conversation with him it seemed he was contented to give form to his vision using whatever means available. In later years, he began constructing what can loosely be referred to as paintings. Living away from the City and having no access to paints, he collected plastic bottles of different colours and on melting them would add different materials such as string, bits of glass, mirrors or bottle tops in different configurations. At my first sight of these works, I immediately thought of Frank Bowling’s work in the tradition of the school of “Found Materials” initiated by Picasso and others during WWII when art materials were scarce. Osaze, being out of touch with art history and the international Art Scene, would not have seen Bowling’s work. One can say, however, that both artists unknown to each other had the same motivation, which made me think of the philosophical expression “all things are connected”. I remembered Carl Jung’s concept of the ‘Collective Unconscious,’ which suggests that similar thoughts helped create comparable mythological symbols in cultures unaware of each other’s existence.

Of particular relevance to Guyana is the enduring problem of recognizing the value of the contribution of the Creative Arts to the development of a country, the word development being used daily in reference mainly to the economy. It has been said in one quarter that the production of literature does not add anything to the economy. The same could apply equally to the Creative Arts as a whole. It means that anyone motivated to create art has to contend with being isolated, existing on his spiritual energy and technical skills to give expression to work that may have only a limited or no meaning at all to the community. This is especially the case where little attention is paid to land as a spiritual and material entity as recognised in the animistic practices of so called “primitive societies”. It therefore becomes difficult to create a national ethos. Another serious matter to consider is the use of a private visual language by the artist which is unfamiliar to the rest of the society. This was Philip Moore’s living experience, which still affects artists. Because of the use, to some extent, of recognisable symbols in George’s work, understanding his presentations was possible. Osaze’s work, by contrast, was less readable because the visual language was less familiar. Were this not the case, it is quite possible that word of Osaze’s creations could have resulted in individuals and institutions offering him valuable support.

A solution would be found in an educational policy that pays attention to visual education (as is the case in Cuba) which embraces anything containing information in a visual format from artwork to the infographics now used the world over. Regrettably, now in Guyana the presence of artists is only recognised and their services only required when national events, festive and other occasions require the use of “visuals”.

Serious artists have to endure isolation, and hopefully not accompanied by poverty as in Osaze’s case. Available options include producing work to suit the “something nice to look at on the wall” market; having work collected by expatriates who recognise its value; finding a job that allows them to pursue their vision, as I did early on; departing for foreign shores, where they instantly become marginalised; and being fortunate enough in the UK to find some support as did Aubrey Williams, Frank Bowling and Denis Williams, who eventually rejected that scene to return to Guyana. We now reaffirm the need for visual education to be part of our education policy.

In George and Osaze, we have two spirits, who, fuelled by their inner visions, found a way, however difficult, to continue to give expression to them. There are lessons for all of us to be found in the lives of both artists: George the recognised and Osaze the unrecognised. May their spirits continue to prevail in whatever domain they have come to rest.