By Alim Hosein

The loss of four artists in short succession has been a great blow to Guyana, an axe to the root of its art, given this country’s tiny population, and the small number of persons engaged in art. The countrywide Guyana Visual Arts Competition has attracted over 200 persons each time since 2012, but the number of persons who pursue art as a full occupation or as a major part of their life is exceedingly small.

Further, when the artists we lose are those who have been doing the kind of work which helps to give character and direction to our art and national life, then the loss is more deeply felt. The four artists remembered here each made a valuable contribution to the creation and existence of Guyanese art.

Osaze

He was well-known in the Art Room at UG. He was unconventional and often controversial, but in a good, not offensive, way. Osaze is the only name he was known by when I was a new student in the 1980s at the university. Osaze was close to the WPA in those interesting days, and an example of its grassroots pull; he was one of the many ordinary people who gravitated naturally to the party.

The WPA did not have a distinct cultural arm, but Osaze was part of such a component within the party through his art which was sculpture, and his talent as a drummer. The WPA was very cultural in its politics and its contact with people. The fact was that the WPA had a great following among ordinary people and the arts that were close to the people played a big part in their political movement.

Osaze’s sculpture and drumming are intricately linked to the African heritage of Guyana. In terms of politics, these fit in well with Walter Rodney’s practice of groundings with the people. Osaze’s style of sculpture also fits into what Denis Williams had dubbed “the village movement” – the free-form, expressive style of sculpture using Guyanese hardwoods that was created by artists who largely lived in the rural areas of Guyana. It was not an organised movement but a natural production which grew out of the artists’ intuitive feel for form and their skill in working wood, and it was linked to the art of the motherland, Africa.

One of the works that Osaze is remembered for, I think, is an iconic sculptural bust of Rodney at the microphone with his jutting Afro hair and his beard – based on a silhouette picture published in Dayclean, the party’s newspaper. He made a clay sculpture based on the picture and painted it black, and it became a popular sculptural image after Rodney died.

Francis Ferreira

Nature was Francis Ferreira’s life-long theme. In his social and economic life, as in his artistic life, he stayed close to nature because of his abiding love for it. He followed this passion from a young age, long before he knew about environmentalism and green economies, and long before these were important concepts in global life. He was able to continue authentically pursing nature as a theme even after the global economy woke up to the importance of the environment because, to him, nature was a meaningful reality. To him, nature and the environment never became excuses to just jump on a bandwagon. This was because he lived close to nature, being a farmer whose father was also a farmer.

Ferreira was also a part of the village movement tradition. As the years went by, members of this movement, mainly sculptors, eventually began to display their work on the Main Street Avenue, close to the Bank of Guyana. These artists ultimately became known as “the Main Street Artists” or, “the Pavement Artists”. Ferreira was part of this group. He identified with them and exhibited with them, and he also had a role as an executive member and a spokesperson for the group.

He was always engaged in discussions about the state of art and the condition of artists in Guyana. He contributed to public discussions on art, including the formulation of the National Cultural Policy, representing the arts and interest of small artists.

Within the pavement artists group, Ferreira’s work was slightly different because of his overwhelming preoccupation with nature. He was not so much Africanist or African-oriented as naturist, but this integrated well with the work of the pavement artists. He also held individual exhibitions of his work. In 1993 he mounted a major exhibition of his work fittingly entitled “In Unity with Nature”. His sculptural expression of nature took the form of masses and lines of wood, contrasted by empty space and free-flowing shapes in which natural forms, especially vegetables and humans in family groups, abounded. Some of his works were “Sun God and the Nature Children”, “Fruit of Life” and “Climbing the Tree of Life”.

Two of Ferreira’s proudest moments came in 1979, when he won a prize for sculpture at the National Exhibition of Visual Arts and very recently in 2018, when he won second prize in Sculpture at the Guyana Visual Arts Competition and Exhibition (GVACE) in a field that included such names as Desmond Ali, Josefa Tamayo, Oswald Hussein and Ras Iyah. He was an avid gardener and was always transforming his farm into a nature resort.

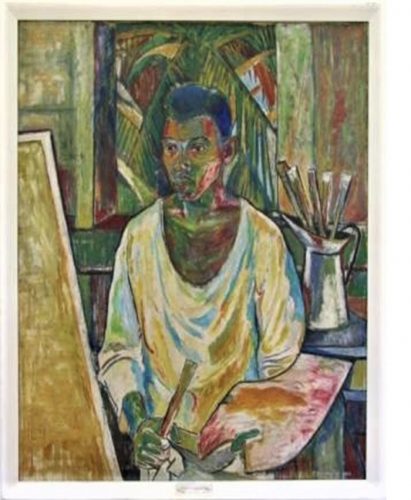

Patrick Barrington

Patrick Barrington was part of the loose group of young people who took Guyanese art from its pioneer beginnings into one of its greatest stages. After the early work of the artists such as Hubert Moshett, Vivian Antrobus, Reginald Phang, Basil Hinds and R G Sharples, who had learned from the classes held by expatriate artists, a new set of Guyanese including Stanley Greaves, Donald Locke, Ron Savory, Emerson Samuels and others began breaking new ground. They continued the focus on local things as did the previous artists, but they also moved away from the British school influence and found more inspiration in the modernist trends of European art.

Barrington was part of this development. Indeed, one of his most famous works which remains in Guyana in the National Collection is his “Self Portrait,” done in 1957. This arresting work shows obvious influence from Picasso, but the curious blend of readiness and hesitancy in the face of the artist is a good statement of the Guyanese artist setting out to create art in this country. This painting is one of the great portraits in Guyanese art, and it was featured in the book Faces of Guyana (2015).

One of his friends, Sue Balding, who wrote his obituary in the Guardian newspaper, reported that Barrington was born in Georgetown to working-class parents, and that he travelled to London on a scholarship from Bookers. He enrolled in art school, but later earned his living as an electrical engineer, although he continued painting, exhibiting his work at the Royal Academy, and doing commissioned artwork.

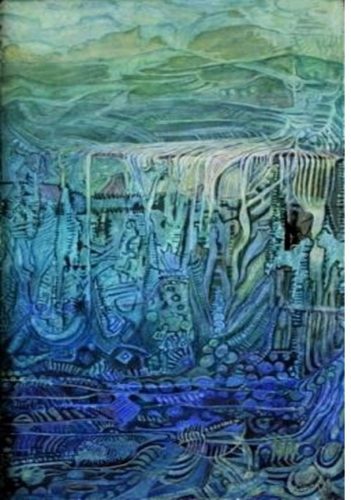

George Simon

Although George Simon enjoyed far greater global acclaim and national recognition than Ferreira, Osaze or Barrington, he is one of their company as far as the roots nature of their work is concerned. His passing is a tremendous loss to Guyanese art, not only because of the important artwork which he produced, but also because he created a whole new movement in Guyanese art. As an artist, he contributed a unique and lasting chapter to the building of Guyanese art for over 40 years. But Simon also opened, through his own creativity and through his own seeking, a new flood of creativity in Guyanese art and culture, which will be forever part of the Guyanese identity and will help to sustain and nurture it.

Others have written correctly about Simon’s greatness as an artist. But there was a driving force that made him such. He was a seeker. His early career as an artist was marked by exploratory work in which he tried to find himself as a person and as an artist. Adopted by a Christian priest after his father died, he travelled as a young man to England and while there, studied art. His training was in Printmak-ing at the University of Portsmouth. The clean, geometric nature of this kind of art with its solid colours was reflected in the paintings in Simon’s first exhibition at the then JFK Library after he returned to Guyana in 1978. He was trying to find a way to paint. He was also looking for subject matter to move away from the academic type of paintings he exhibited. His subsequent paintings saw the beginning of an Amerindian theme, where he began painting indigenous people and images such as bows and basketwork. But the painting style was still descriptive of the people, indigenous artefacts, and the landscape. In discussing the artwork in the JFK exhibition with me in an interview in 2005, he volunteered that he was “uneasy about that because I was copying all these images and I didn’t know what I was doing”.

The path of seeking that he was on was an artistic one, and a personal one. As he confessed in an interview in 2006, for much of his life he struggled with a negative perception of himself as an indigenous person, and a shallow understanding of what it meant to be an Amerindian. At that time, in the 1980s, he was working as a lecturer in the fledgling UG Art programme, and he was also a lecturer at the Burrowes School of Art. He was reading and thinking about the spiritual aspect of the world and the universal reflections of this spirit.

From around 1973, he had moved away from his Christian upbringing and began exploring other ideas about spiritual life such as Taoism. These explorations led him to the realisation of the spiritual power of his own people. He began to understand the power of Shamanism and the Shaman as one of the kinds of persons who had “clear sight and knowledge of the mystical pathways” (George Mentore, 1993), and moreover, the power to access the mysteries of the universe. One of his key breakthrough paintings coming out of this understanding is “The Shaman’s Journey Along the Milky Way,” which is a fantastic image of the Shaman journeying through time and space. In 2006, he held an exhibition of paintings and drawings, “Shamanic Signs”, at Castellani House. Another discovery he made was that of the similarities among different cultures in different parts of the world, the presence of a global connection among peoples.

Simon also began working as a field assistant to Williams through the Walter Roth Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology in 1985. His work took him into interior locations. This was a fortunate turn of circumstances. As he said in an interview with Anne Walmsley in 1994-5, archaeology helped him to turn his attention inwards, to be more confident about his private vision, and to understand that his people had a long and rich history which was worth revealing. He was still actively painting. The exhibition he had in 1991 – a retrospective of his work between 1981 and 1991 – showed his early painting style applied to indigenous themes such as “Indian Shooting Fish and Wai Wai Body Adornments”.

But among these was the “Toka” series of five paintings, named after a village in the north Rupununi where he did archaeological work. This series showed a drastic change in his painting technique, and in his vision and understanding. Where the previous paintings were about surfaces, the almost totally monochromatic “Toka” paintings were about hidden depth, about history and life beneath the surface. They were an expression of, and a counterpart to, his archaeological understanding. These paintings were about the discovery of a whole life and purpose. His art never looked back since then, and he himself moved forward with a new and powerful sense of himself and his roots. One of the powerful paintings of this period is “Oriyu-Shikaw Kaieteur, Home of the River Spirit” which is a painting of Kaieteur Falls as it was never imagined before or since, with layers of water, spirits, history, land and myth.

Here is where the true art and mission of Simon’s life lay. He had gained an insight into himself, but he knew that this was an insight into the indigenous people too. From around 1988, he had started encouraging persons in his home village of Pakuri (formerly St Cuthbert’s Mission) to start producing artwork. This was a revolutionary move, since there had been no thought that the indigenous people could produce the kind of work which could be exhibited in a fine art museum. Art from Amerindians was thought to be restricted to straw, shell, bead, and other such work which had become a feature in craft stores after Guyana gained independence. Individual artists like Eddie Fredericks (painter) and Stephanie Correia (ceramist and painter) had emerged in the 1960s but only Correia had gained national recognition. The young men with whom Simon worked did not just produce art. They displayed astonishing and totally new forms in sculpture. This was the dramatic unveiling of a hitherto unknown imagination, one that no one knew existed right here in Guyana.

One of the Pakuri villagers, Oswald Hussein, Simon’s brother, began entering national competitions and won the National Exhibition of the Visual Arts in 1989 and 1993 with his powerful sculptures. In 1991, the new artists began exhibiting as a group with a first exhibition at the Hadfield Gallery. In 1998, they declared themselves “the Lokono Artists”, thereby claiming their ancestry. Other exhibitions followed regularly in the ensuing years. The group gradually became larger, and their exhibitions even came to include the work of other artists of indigenous heritage such as Winslow Craig. This indigenous sculpture carried Guyana’s art in the 1990s and into the new century. From 2002, they used the concept of a moving circle to name the group’s constant evolution. Indeed, the Lokono artists had become such a strong force that they even held an exhibition abroad – in Barbados in 2003.

Simon nurtured the group, and developed his own art, which was painting. He developed a multi-layered painting technique along with highly articulated surface markings creating rich canvases that echoed depth, history, time, and spirit. He also allowed his intuition more freedom to guide his work. In successive series, he explored significant imagery such as bones, serpents, sperm, knives, leopards, and other images. Much of this was fuelled by his research into cross-culture and his travels in places such as Chad, France, and Haiti where he connected with local artists who shared his vision. Typical of him, he also founded and nurtured groups of artists in the different countries he lived in. These travels and research confirmed his understanding of a universal spiritual connection among humans, which is often reflected in the same or similar motifs, symbols, or images appearing in the religion and art of many different cultures. One good example of this is his focus on the serpent, an interest which began with his discovery of an Amerindian burial urn with a serpent motif in early 1994 in Paramakatoi. He picked up the serpent theme again when he was in France, and again in Haiti in 2002. Further research led him to the great serpents of South American cultures, Indic snake worship and Kudalini energy.

In later years, Simon’s paintings became more spacious and open, with wide vistas but they still showed his interest in plumbing the different, often hidden, levels of being. The realisation of these depths, the release of the energies that they contain, the “discovery of companion” (Martin Carter) which they promote, and the freedom of being that they allow us to adopt in time and space, are among Simon’s contributions to his people, to Guyana, and to all of the world.

Alim Hosein, an artist, critic, and linguist, is Head of Language and Cultural Studies at the University of Guyana.