Gaiutra Bahadur’s book Coolie Woman was shortlisted in 2014 for the Orwell Prize in Great Britain. An assistant professor at Rutgers University in Newark, New Jersey, she writes for The New York Times Book Review, The New York Review of Books, The New Republic, The Nation, and Dissent, among other publications. The recipient of literary residencies at The Bellagio Center in Italy and the MacDowell Colony in Vermont, she is a two-time winner of the New Jersey State Council on the Arts Award for Prose and a winner of the Barbara Deming Memorial Award for American feminist writers. She has also been a fellow in residence at the W.E.B. Du Bois Institute at Harvard, the Nieman Foundation for Journalism at Harvard, the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture at the New York Public Library and the Eccles Center for American Studies at the British Library. Born in Canje, Berbice, she earned her B.A. in English Literature, with honors, at Yale University and her M.S. in Journalism at Columbia University. This article first appeared in Tides, the online magazine of the South Asian American Digital Archive (SAADA), where Bahadur currently holds a fellowship supported by the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation to create an online archive of Guyanese immigrants in the United States.

British Guiana’s first elected leader, the son of plantation workers who had arrived in that colony as infants on the same ship from India in 1901, almost became an immigrant in the United States.

In 1936, Cheddi Jagan arrived here on a visa to study at Howard University. In his memoir The West on Trial, he wrote: “The first thing I became very conscious of was the question of colour. Somehow, in the U.S., a non-white is always reminded of the colour of his skin. This was for me an entirely new experience.” He recounted that his classmates, with an exoticizing flourish, nicknamed him Rajah because he was the only student of Indian origin at the historically Black college. In his seven years in Washington, D.C., New York and Chicago, he repeatedly found himself an outlander in the borders between Black and white, an appalled witness to segregation. He also found that the color of his skin, less dark than other Indian-looking students forced in the South to sit in the rear of streetcars and buses, gave him the ability to choose which side of the American binary to ally himself with.

Told that, as an “East Indian,” he could go to cinemas in white sections of Washington, D.C., he chose the “Jim Crow cinemas.” In theatres with partitions down the middle, he chose to sit in the Black section. On a streetcar in Virginia with a Howard classmate who was ordered to the rear by the conductor, while Jagan was not, he joined his friend in the back. In Miami, he refused to take a hotel room because a Black fellow traveler’s reservation was canceled as soon as the front desk set eyes on her. If segregation aroused Jagan’s conscience, he also benefited from his in-between status. As a dental student at Northwestern, for instance, he could take a room close to the university while his friend, a fellow Guianese who was Black and more well-off than he, couldn’t get lodgings in that part of town.

Jagan spent his summer breaks from Howard, in 1937 and 1938, in Harlem, playing cricket with fellow West Indians and working multiple jobs. Among other things, he sold patent medicine, ascending flight after flight in overcrowded tenements touting Epsom salts as a cure-all, regretting later that he “had helped in the exploitation of poor people by purveying junk.” He might well have sold it to a family from British Guiana, living at West 111th Street, in a neighborhood with immigrants from the Bahamas, Bermuda and the Soviet Union: an elevator operator named Henry Sivenandan, his wife Agnes and her widowed sister Rose Persaud, who both worked in a dress factory, and the couple’s baby Saundra. The 1940 census counted them there, their races all noted as “Negro.” Jagan might have guiltily pitched them his Epsom salts, just as it’s possible that, playing cricket, he might have encountered another Guianese with an Indian last name, John S. Bahadur. An infantryman with the Harlem Hellfighters, described as “colored” on his enlistment card in 1936, Bahadur lived across the street from St. Nicholas Park. James Khan and David Dinally (likely an alternation of “Deen Ali”) might have turned up at cricket games too, a respite from jobs as, respectively, an elevator operator and hotel worker. The two men, also Guiana-born, also with Indian last names, also identified by census takers as “Negro,” were lodgers in a female-run, African-American household headed by a divorced seamstress from Kentucky, at West 116th Street, a few blocks east of Morningside Park.

These cross-ethnic lives tucked quietly into official records suggest that Jagan may not have been the only East Indian from the West Indies choosing where to sit in a society built on the binaries of Black and white. Indeed, these Harlem neighbors appear to have taken more radical steps than he ever did. Details in the archives from a century ago hint either at kinship or calculation, mistaken identity or willful passing by those who crossed or resisted the lines of race, when lawmakers and scientists were busy denying its fiction and its fluidity. They provide tiny glimpses of people who slipped through crevices in the walls meant to keep them out, pointing to an untold prehistory of Indo-Caribbean migration.

For immigrants of color, or our descendants, our origin stories in the United States of America often begin in or after 1965, with the law that overturned half a century of immigration quotas intended to keep America white – specifically of northwestern European “stock,” to use the language of early 20th century scientific racism. A series of laws in the late 19th and early 20th centuries excluded or drastically restricted newcomers from the Asian and African continents. For West Indians, however, the story is more complicated. There have been three periods of significant West Indian immigration to the United States, and the second wave, from 1900 to 1930, bringing more than 150,000 people, coincided with that infamous and virulent period of nativist sentiment and legislation.

The Western Hemisphere wasn’t subject to the caps that governed how many people could come from, say, Greece versus Germany or Italy versus Norway. Under the provisions of the law, anyone from independent countries in the Americas – including Cuba, the Dominican Republic and Haiti – could enter the United States as immigrants without being subject to quotas. And people from the islands and territories of the British West Indies, British subjects not yet politically free, fell under the quota for Great Britain, which had the second largest number of immigrants reserved for it, after Germany. It’s accepted as a truism that very few West Indians of Asian origin took advantage of these openings in the barricades erected against people of color––that they did not begin to immigrate to the United States in significant numbers until the 1970s.

But, the contours of this premise may be softer than presumed. It hasn’t yet been fully examined to reveal any blurring at the edges. Nor have the reasons behind it been articulated by scholars of migration. It’s true that South Asians in the Caribbean were not as equipped, socioeconomically, to emigrate in this period. With indenture, the system of bonded labor that brought them to the Americas, ending in the early 1920s, most Indians in Guyana, Trinidad, Jamaica and elsewhere in the Caribbean were still plantation laborers or not far removed from that exploited existence. But there was another, fundamental explanation for why they did not come to America in large numbers in the early- to mid-twentieth century: at the same time that the last indenture contracts were expiring in the West Indies, the U.S. Congress was passing legislation that banned Asians from entering as immigrants. In 1917, it made all of Asia a zone of exclusion. And in 1924, it barred any immigrants who were not racially eligible to become U.S. citizens. Asians, even those generations severed from Asia and living in the Western Hemisphere, couldn’t enter the U.S. legally because only white and Black people could naturalize here.

And that, rather than the bitter realities of anti-Black racism, was why Jagan did not become an immigrant in America. He might easily have become one. Although he had come to the United States as a student—students were exceptions to the 1924 ban and are not officially immigrants—he had married a Jewish-American woman, Janet Rosenberg, in Chicago and was working there as a dental technician. Although trained as a dentist, he couldn’t practice as one, because only citizens were allowed to take the state board examinations to do so. Ironically, he could serve in the army without citizenship. As he wrote in his memoir, “… the United States authorities, unwilling to let me become a citizen, were quite willing to draft me as a private!” With the U.S. Army knocking, in December of 1943, Cheddi Jagan returned to British Guiana, where his new bride soon joined him and where, together, they co-founded the multiracial, socialist party that fought for independence.

It begs asking: How did other Guianese of Indian origin, if they didn’t quit the United States, respond and adapt to the bars against citizenship and immigration? Vivek Bald, in Bengali Harlem, documents the lives of other working-class South Asian men, Muslim peddlers and seamen from Bengal, who married African-American women as they navigated a country hostile to “Hindoos,” a racialized term that included both Hindus and Muslims. In the years after World War I, some of them lived in Central Harlem alongside a few Indians from British Guiana, Trinidad and St. Vincent. Bald names eight. Searching historical records in an admittedly ad hoc, quick-and-dirty way—using the common Indo-Caribbean surnames Persaud, Khan, Singh and Baksh and focusing on people with British Guiana as a birthplace and New York as place of residence—I found more than twenty others. The records identified most as “Negro.” Is the implication, then, that they were passing? At least on paper? Bald tells us about African-Americans at the time who donned turbans and robes to pass as “Hindoo” fakirs “to outwit the racial apartheid of Jim Crow.” Is it possible that passing also took place in the other direction, to outmaneuver anti-Asian immigration and naturalization laws?

The records cannot capture motivations, agency or lived realities, the texture of everyday intimacies and interactions. But they do suggest that West Indian immigrants in the first half of the twentieth century were a more complex mix than we have assumed and that black lives and brown lives intersected in ways we might not have imagined. The archives gift us these lives worth noting, worth pondering, especially as we consider the past and plot the future of black-brown solidarity.

Just two months before the 1924 ban took effect, a 23-year old widow named Rose Su Persaud arrived at Ellis Island and declared her intention to go live with her sister Agnes Premdas at the Phyllis Wheatley Hotel in Harlem, founded and run by Marcus Garvey’s Pan-Africanist United Negro Improvement Association.

In 1923, a 22-year old man born in the Guianese capital of Georgetown sailed to the United States, intending to study for six years, having previously been a student in Boston for four years. Immigration officials described Mohabeer Singh as “East Indian.” By 1927, he was married to a Virginia-born woman named Bertha, working as an elevator operator, and applying for citizenship. The 1930 census places the couple on a block full of transplants from the American South and Puerto Rico in Harlem and identifies them both as “Negro.” It describes Singh, then a fruit vendor, as a naturalized American citizen.

That same year, the New York State Reformatory, a juvenile detention center upstate in Elmira, listed a 24-year old Guiana-born man, Mohamed Khan, as a resident. Before committing his unknown crime, he had been a student at an electrical school. He arrived in the United States in 1928. Most residents at the detention center that year were white and native-born, between the ages of 17-28. Khan is described as “Negro,” with a father born in Asia and a mother born in British Guiana.

Then there’s the thwarted love story implied in the entry records of Ajudhia Persaud, a student at McGill University in Montreal and a repeat visitor to New York to see his wife Laika. The couple was separated when he was deported in 1935, after his father’s naturalization was revoked, “due to error.” It’s unclear what this error was, whether it was a case of passing uncovered or whether it was part of the wave of citizenship rescinded after the Supreme Court ruled, in 1923, in the case of Bhagat Singh Thind, that Indians could not claim whiteness and therefore could not become citizens.

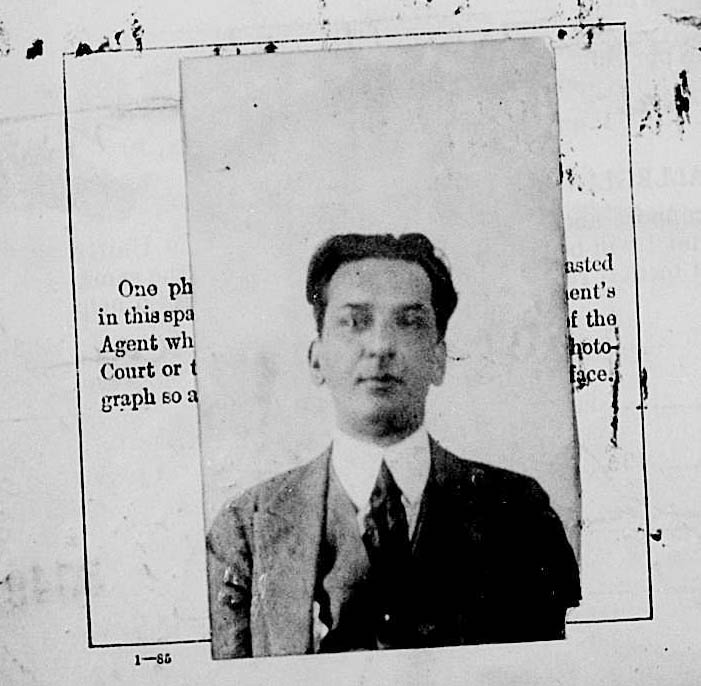

The archives suggest many Indians from Guiana and the West Indies more broadly may have been claiming Blackness; but at least one extraordinary one, who circumnavigated the globe, claimed whiteness, as Thind and other South Asians had in bids for citizenship. The U.S. Census, passport applications and naturalization petitions unfold the story of Mohaiyuddin Khan, a commercial trader who married, then divorced, a German-American woman. At 5’11’’, he was tall and striking, with an aquiline nose, a pointed chin and an oval face. His passport photos show a man who could have passed for Greek or Italian. Indeed, when he landed in New York in 1913, in his mid-twenties, he declared his intention to naturalize and gave his “color” as “white” and his birthplace as London.

He was, however, actually born in Guiana, the son of Gool Mohamed Khan, the prominent businessman and imam who built the first mosque in Georgetown after sailing there from a village north of Peshawar in 1869 and who ultimately returned to South Asia, settling in Calcutta. The younger Khan apparently left Guiana at the age of ten and traced out a seaman’s or trader’s trajectory over the course of his life, traveling across the Malay States, India, South America, Africa, Japan, China, Switzerland, Ceylon and Italy. In 1920, he was living in Brooklyn with his wife Gertrude and her German immigrant family. Khan had become a naturalized U.S. citizen the year before. For six months in 1921-1922, he traveled to London to buy skins and hides as an agent for an A.M. Khan in Asbury Park, New Jersey. His passport applications suggest that he was often away from his wife Gertrude’s home in Bedford-Stuyvesant. The 1930 and 1940 censuses record her shorn of the surname Khan, using her maiden name again and working for an insurance company, with Mohaiyuddin no longer living with her.

The last sight of him in the records is in 1952, at the age of 63, landing in New York after a voyage from England and heading to an address in Greenwich Village.