Ambition is a tricky thing. On its face, the word, which means “a strong desire to do or achieve something,” is innocuous. But its connotation is more complex; it is mired in something that’s not always perceived as good. It invokes ideas of doing too much. Being discontent. Going beyond what is needed. Or required. And it’s a word, in its denotative and connotative meanings, that feels central to thinking of Beyoncé Knowles-Carter, her legacy as a performer and creator, and her newly released visual album, “Black Is King”.

Last month Disney+ announced that Beyoncé was orchestrating a visual album. The album would be her third such, after her self-titled “Beyoncé” in 2013 and “Lemonade” in 2016. Rather than a self-contained collection of music, though, this new film sprung from Beyoncé’s work on the photorealistic adaptation of “The Lion King” last year. Beyoncé’s role as Nala was the inspiration for, “The Gift”, a collection of original music with artists from the African continent celebrating blackness. Rather than a traditional soundtrack, the album reimagined the story with new songs using R&B, hip hop and afro-beats to present new ideas of blackness.

“Black Is King” is the filmic accompaniment to “The Gift”, a year after that album’s premiere. The brief trailer that launched last month precipitated some alarm from black critics concerned that the film, positioned as a celebration of blackness, would instead deify myopic tropes of blackness that were rooted in cultural syncretism, homogenising and essentialising black culture for capitalistic purposes rather than celebrating the multitudes that come with blackness in and out of Africa. “Black Is King” is intentionally cognisant of the multitudes it depends on, though.

Beyoncé, as mogul and as icon, is rooted in capitalism like any contemporary celebrity. And even her charity work, and her recent focus on supporting black business in the midst of a global reckoning on antiblack racism, has not put her beyond reproach. The argument that Beyoncé’s harnessing of blackness functioning only as a mercenary engagement with race and blackness is a facile one, though. To write-off “Black Is King” and its engagement with blackness is to wilfully miss the value of the ambition at work here.

On film, the fourteen songs of the album are tied together by spoken interludes from the 2019 “Lion King” film as well as additional interludes narrated by Beyoncé and other black figures. In an early interlude, she presents the ethos of the piece, “Let black be synonymous with glory.” Even as “Black Is King” functions as film, it is more semiotic and symbolic than specific and narrative focused. A recurring narrative strand recalls the Bible’s Moses as a young baby is put into a basket for his safe-keeping. The barebones of any semblance of a narrative is the story of “The Lion King”, reimagined with humans. It covers, very loosely, the story of a young boy’s journey to manhood and his realisation of his own self in a hostile world that he must tame. But narrative and story is less significant than the central motifs and images that the film communicates that move beyond a single clear narrative.

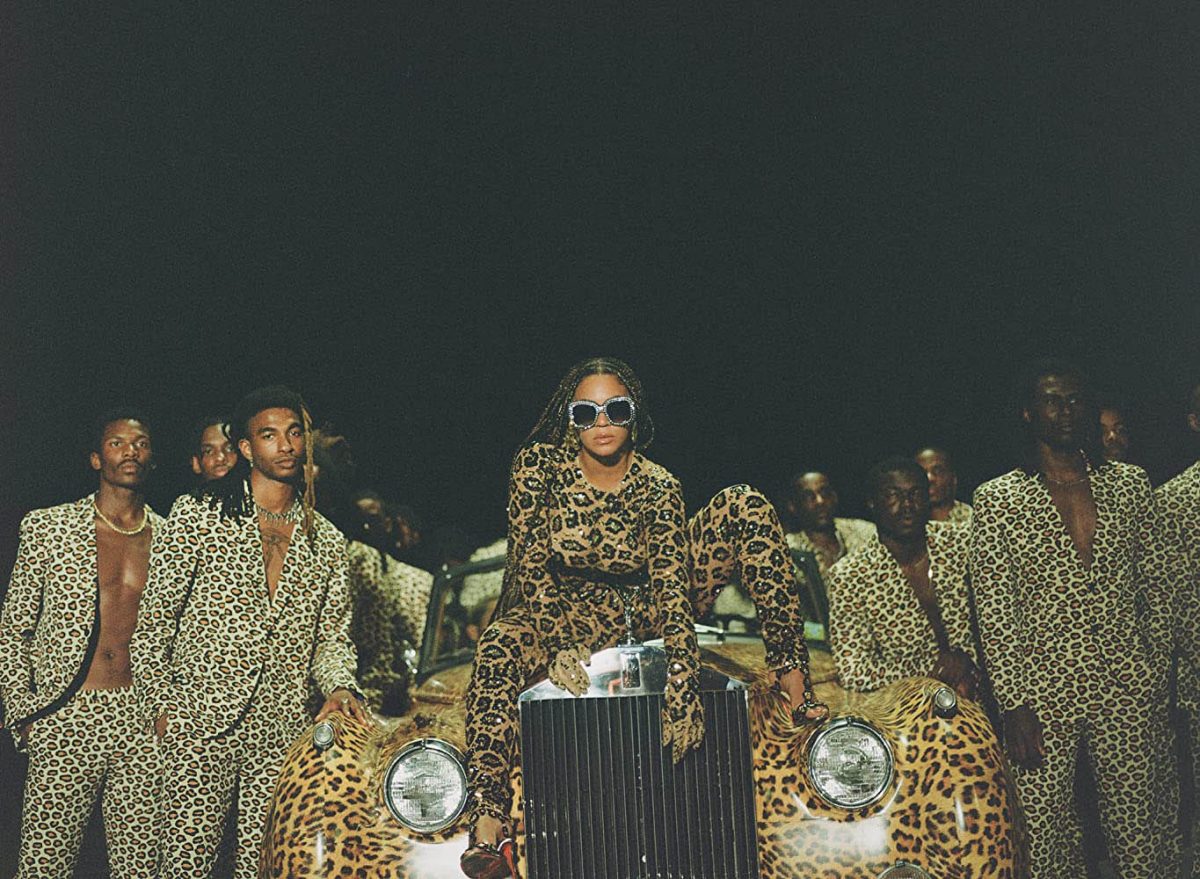

Midway through when Beyoncé and husband Jay-Z feature in a lavish video that reimagines the ideology of Timon and Pumba’s “Hakuna Matata” lifestyle as a lavish postmodern life of excess, the idea of the word “mood” as an aspirational, spiritual state of being is made manifest. Because “Black Is King” at its best is working towards being that whole mood. The whole mood. And that is a cemented facet of its ambitiousness. Blackness, as a concept, as an ideology, as a race, as a culture, cannot be filtered down to 85 minutes of vibrant colour. It is why signs and symbols work better than coherent narrative, and it’s why even as the cultural syncretism points can be examined, remaining there feels inexact. To do so would be to miss the value and purpose of what Beyoncé is doing here. This is ambition writ large, ornate and sumptuous but also challenging and thoughtful. “Black Is King” does not demur, but is intentional about its desire to represent and re-present the multitudes.

It is significant, then, that the ‘Mood 4 Eva’ sequence does not represent the gamut of the film. The film subverts notions of flossing and arrogance. Instead, it recognises that blackness contains multitudes and so “Black Is King” moves from explicit biblical references to secular allusions about finding god within oneself. It directly references cultures of African countries – Jozi, Zulu, Yoruba and more. It invokes the African diaspora with a celebration under the Pan-African flag designed by Marcus Garvey. It moves from images that evoke pre-colonial Africa to images that are distinctly contemporary on an off the continent. At surface level, one might call the plethora of references and styles hectic. But, to consider it deeper is to recognise that Beyoncé invites us to become suffused in the sensations. It’s a feast. It wants to overwhelm us. The camera moves with dizzying precision changing from locale to locale. Like the many bodies of water that emphasise Beyoncé’s interest in water imagery, there is much to wade through here.

When Beyoncé narrates early on, “to live without reflection for so long might make you wonder if you even truly exist,” the film presents itself as a reflection as each section seems to be working in different ideas. The opening, ‘Bigger,’ uses water-imagery to good effect, ‘Don’t Jealous Me’ is a haunting, and titillating flirtation with danger, ‘My Power’ is a celebration of feminine ferocity (with some of the film’s best choreography). There is so much to take from here. The potential problem in this is that the film becomes easy to dissect, its parts lending themselves to judgments of their superiority, but this doesn’t feel like a bug. Instead, the discrete parts making up the whole feel inherent to the film’s own complications.

Even as it espouses that Black is king, “Black is King” is at its eclectic best when it recognises and acknowledges that Black is also Queen. And this notion comes together in the strongest sequence in the film – the ‘Brown Skin Girl’ entry where Beyoncé is accompanied by Nigerians singer Wizkid and Guyanese singer Saint Jhn. Musically, the sound is self-assured and smooth as it confidentially rejects notions of colourism that have plagued black women. As a piece of visual-media the song moves from excellent to unimpeachable. It is the number least bound to the strains of “Lion King” significance, and instead features a brief story of black womanhood made mortal but also immortal. The central motifs are a debutante of teenage girls, an adolescent girl observing and images of women around her as Beyoncé, her family and celebrities celebrate black womanhood.

But the number takes on greater resonance when the camera moves from the celebrities to images of regular black women and families around the world. Unadorned. Simple. Normal. It is the moment that the project justifies itself as film, as the images matched with the lyrics become profounder. It speaks to the accidental symmetry of the film’s release. In a way, “Black Is King” may seem late. “The Lion King” was one year ago, and the visual album features no new music within the centre of the film. Why now? And yet the film also seems preternaturally on-time. Who could know that America, and the world, would be seeing a reckoning on blackness in the world? Who could predict that in 2020 “Black is King” would seem, not just prescient, but terrifyingly necessary?

Last week Guyanese activists painted Black Lives Matter on the square before the 1763 monument – a symbol of black activism and rebellion as a sign of hope. The act, inexplicably, spurred mixed reviews. It was a reminder that emphasising and celebrating blackness always becomes more controversial than it need be. Last year a student in my niece’s class told her, unprompted, “Black girls aren’t pretty.” My niece is five years old. It is a reminder that race, and racism, is suffused even into the fabrics of those you won’t imagine. These are just two incidents that made “Black Is King” feel even more vital. It’s that ambition that is so central and invaluable here. Beyoncé dares to do much. I’m tempted to say too much, except that would be play into the narrative that one can be too ambitious. That there is a limit to the experiments and risk that a black woman ought to take. So the images where Beyoncé’s daughter Blue Ivy replicates her mother’s actions and swagger in ‘My Power’ feel like an essential challenge.

It speaks to why ambition is complicated and argues for why “Black Is King” for those complications. Because it challenges notions of being satisfied, of being comfortable. Blue, like Beyoncé, dares to move beyond our ideas of black girlhood and womanhood. And it’s a microcosm of the film’s larger interest. It is why “Black Is King” feels fulsome even when its semiotics become occasionally more muddled than distinct. In a way it feels baked into the ambition here. So much is at work here. By definition the muchness that is baked into this piece — too schematic for a traditional film and too intentionally part of a whole to be individual pieces — is its excellence. “Black Is King” becomes supreme by the way it seems to debate and argue with its multiple identities. The film retains a sense of identity as something fluid and malleable rather than concrete and implacable.

As the film comes to its close, a male voice intones, “As kings, we have to take the responsibility of stepping outside the barriers they’ve put us in for the next generation.” “Black Is King” is stepping out of boxes. And to do so requires ambition. It requires risk. And it requires something that moves beyond the ways we recognise music, film and the limits of their differences. “Black Is King” becomes essential for its raw ambition and tenacity. When a guest narrator reminds us that true kings and queens recognise that sharing spaces, ideas and values strengthens – rather than weakens – communities, the film nods to the competing multitudes it contains. It is this complexity, and the film’s disinterest in being palatable, that announce “Black Is King” as a gift.