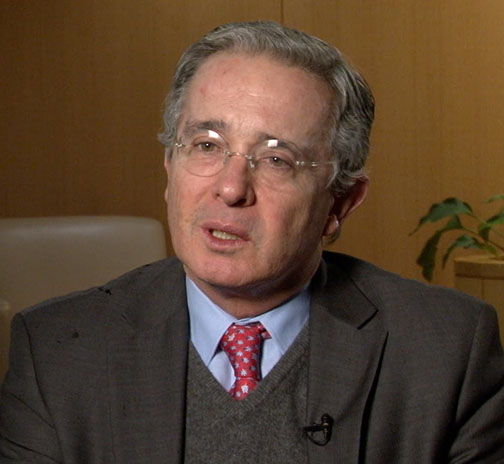

BOGOTA, (Reuters) – The house arrest of former Colombian President Alvaro Uribe in a witness tampering case is unlikely to dim his influence, but has focused his party on justice reform proposals they say will bring more consistency to the judicial process, according to politicians and analysts.

Uribe, perhaps the country’s most divisive politician, was placed under detention by the Supreme Court in a unanimous Tuesday decision that cited potential for obstruction of justice.

The ex-president, who now serves as a senator, has repeatedly declared his innocence amid accusations his allies undertook witness tampering in an attempt to discredit allegations that Uribe had ties to right-wing paramilitaries.

It is the first time ever a Colombian court has detained a former president. Uribe supporters say the case is a set-up and that the high courts are biased against him.

Kingmaker Uribe has shepherded two successors to power since the end of his second term in 2010, including current President Ivan Duque. Uribe also founded his own political party, the Democratic Center, which now holds more than 50 seats out of 280 in Colombia’s bicameral legislature.

The court has so far not barred Uribe from his congressional seat and he is still his party’s guiding light, said Democratic Center senator Santiago Valencia.

“He remains our leader,” Valencia told Reuters in a video interview. “Of course it’s a hard hit for the party.”

Uribe’s detention will laser focus the party on a judicial reform already under initial discussion in Congress, said political analyst Sergio Guzman of Colombia Risk Analysis. The proposal seeks to consolidate the high courts into one and give courts budgetary autonomy, among other things.

That could be to the detriment of other government plans – from labor to tax reform, Guzman said.

Duque and other Uribe allies have said his house arrest is unfair, comparing it to former rebel leaders who have been allowed to remain free by another court while their war crimes proceedings move ahead. The guerrillas received special terms under a peace deal reviled by Uribe.

The party argues the courts’ approach is inconsistent, and believes the proposed reform would reduce such inconsistencies.

The Democratic Center is using Uribe’s detention as a “pretext” to push the judicial reform and to begin campaigning for the 2022 elections even amid the COVID-19 pandemic and economic fallout, said leftist senator Jorge Robledo.

“It is the completely wrong moment (for a justice reform),” Robledo said. “What will citizens who are dying of hunger, who are sick, whose children don’t have education, who don’t have anything with which to pay rent think when they see the Democratic Center looking to win elections?”

Senator Valencia said the justice reform push had been inspired not only by the ex-president’s case but by corruption allegations and long case delays. The bulk of the government’s reform agenda should not change, he added.

Duque has been grappling with low approval ratings and congressional resistance for much of his term, which ends in 2022. He has vociferously defended Uribe, saying he is a man of honor who should be allowed to defend himself while free.

“We were seeing that COVID and COVID recovery were going to greatly determine President Duque’s legacy, and how he would be seen by Colombians and by history,” Guzman said. “I think now President Duque’s legacy is much more tied to how Uribe fares judicially than any other thing.”

The president’s defense of Uribe “is yet another stain on the legacy of Ivan Duque,” Robledo said.

Uribe faces a prison term of up to 12 years. A conviction would put him in the ranks of other former Latin American presidents who have served time, including Brazil’s Lula da Silva and Peru’s Alberto Fujimori.

Uribe is best known for mounting an aggressive offensive against Marxist guerrillas during his tenure. He and his family have long been accused of links to right-wing paramilitaries, and his brother Santiago is facing a paramilitary-related murder charge, which he denies.

Uribe’s opponents hailed the court’s decision as a long-awaited victory for judicial independence and celebrated with gatherings and on social media. But they many not want to count their chickens just yet.

The case does not mark the beginning of the end of Uribe as a towering political figure, Guzman said.

“Uribe has many lives.”