Thomas Harding is writing a book about the 1823 Demerara rebellion. To find out more about him or his previous books go to his website www.thomasharding.com or you can email him at 1823@thomasharding.com

I am writing a book about the Demerara Insurrection of 1823. The uprising led by Jack Gladstone and his father Quamina. And I would love your help because, for now, I can’t get to Guyana …

Why, you may ask, am I, an Englishman, interested in the 1823 insurrection? Let me try and explain.

In 2015, I wrote THE HOUSE BY THE LAKE, which told the story of my father’s family who were Jewish and had to flee Nazi Germany in the 1930s. Since then, I have worked with the residents of the local village to transform my family’s house it into a centre for education and reconciliation. I have personally received reparations from the German government. It has been a remarkable journey.

The next book I wrote, LEGACY, was about my mother’s family, the Salmons and the Glucksteins. During my research, I learned that they had started their tobacco business in England in 1843 and by the end of the century it had become the biggest tobacco retailer in the country. My family bought most of their tobacco from Virginia, which means that it was almost certainly cultivated by enslaved people.

In other words, the shoe was now on the other foot. If I was willing to identify as a victim in my father’s family, to receive reparations from the German government, to talk about inter-generational trauma and the need for reconciliation, then surely I had to take some responsibility for the actions of my mother’s family and how they had built their first fortune through slavery.

Which is why I am writing a book about Britain’s role in slavery (via the 1823 Demerara Insurrection) and the impact it has today. Part of this will be an attempt to answer the following three questions: What was my family’s connection to slavery? Should I do something about it? And if so what?

When I was taught about slavery as a child, I was told that ‘Britain freed all the slaves’. That was our role, we were the heroes of history. I learned about William Wilberforce and the Abolition of Slavery Act of 1833. We were never taught that British captains commanding British boats manned by British sailors transported more than 3 million men, women and children who had been kidnapped from Africa. Nor was it ever explained to us that British people owned the plantations in the West Indies where hundreds of thousands of enslaved people were forced to work, and die. Nor that thousands of British businesses— the bankers, insurance brokers, the commodity traders and the sellers of sugar, cotton, coffee and tobacco (including my mother’s family) — built their profits from the system of slavery.

It is like a national amnesia. If white British people speak about slavery, which is rare, it’s about the plantations of the American South. And we tut-tut-tut about how evil they are, those slavers, those plantation owners. As for the West Indies, it is treated as ‘over there’, not ‘our responsibility’. Even though, in another breath, we proudly talk about the British Empire and all that we accomplished.

It should be said, that something seems to have shifted since the killing of George Floyd in the US, and the dramatic growth of the Black Lives Matter movement. A few journalists are now writing about Britain’s role in history, more people are asking questions about their families, and there is even talk about reparations.

But why am I interested in the 1823 Demerara Insurrection? Because during this uprising the enslaved people displayed remarkable courage, fortitude and grace as they fought for freedom. To organise a rebellion that spanned more than 60 estates and included over 12,000 people — four or five times larger than Cuffy’s Rebellion of 1763 — must have taken extraordinary planning, preparation and strategy. More than this, the leaders of the insurrection were committed to the avoidance of violence, except in self-defense, which in itself is remarkable compared to other uprisings in the region.

In addition, the Demerara Insurrection had a dramatic impact on how slavery and enslaved people were perceived in the British Empire, leading to an astonishing increase in support for the Anti-Slavery Society in the UK, which in turn played a role in the enactment of the Abolition of Slavery Act in 1833 — though so-called ‘emancipation’ didn’t take place until years later.

Which is why I am so keen to visit Guyana.

So, today I tried to book a flight from London to Georgetown, but the website said ‘international travelers are not allowed to visit Guyana’. Of course, this is because of the Covid pandemic which has disrupted every country around the world. And so I have to rely on the kindness of others.

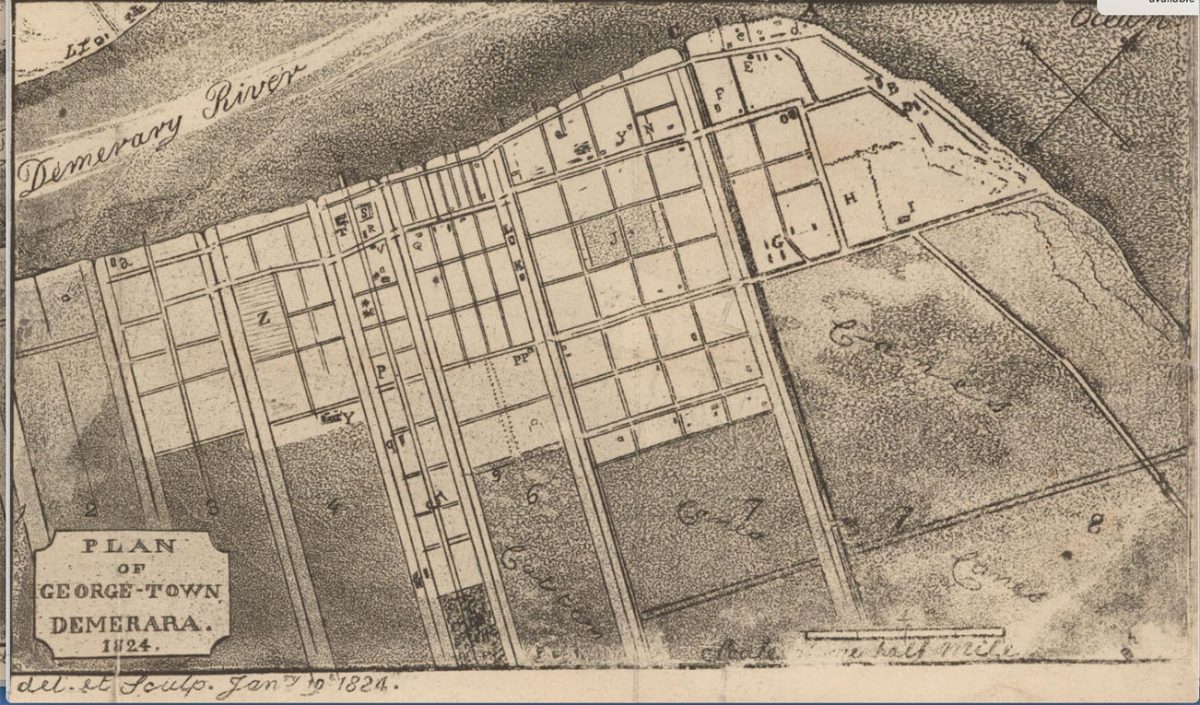

I live in a small village in Hampshire, England, not far from Portsmouth, close to the South Coast. On the wall next to my desk hangs a red pin board with maps of Georgetown from the nineteenth century. The roads have names like ‘Murray Street’ (now Quamina Street) and ‘Back Dam’ (now Cummings Street). There’s the ‘Camp-House’, ‘Store Keeper’s Ordinance’ and the ‘Old Parade Grounds’. On the same board is a list of plantations, number 1 through 65 with names like Chateau Margot, Plaisance and Bachelors Adventure. I want to visit these places as well. To see how they fit in the landscape. To feel their size, to hear the sound of the wind coming off the ocean, to experience how things have changed since 1823. But I can’t. Yet.

In the books that I have on my shelf, I read the names of the foods that could be purchased at the Stabroek Market at the start of the 19th Century. Saltfish and bangamary. Dragonfruit and plantains. Pepperpot, Foo Foo and cassava. I have eaten plantains and cassava before, but not the rest. How do they smell? How do they taste? I wonder about this as I go downstairs and make myself a cup of tea and nibble on a ginger bread biscuit I purchased this morning at my local post office.

I want to hear the birds in the trees and the bushes in the Botanical Gardens on Vlissingen Road. From Tripadvisor I see there are Macaws and Toco Toucans, Orange Winged Parrots and Yellow Crowned Amazons. Do they squawk or whistle, trill or twitter? Instead, I hear the screech of the red kites that glide the warm air currents outside my office window.

I want to smell the fragrance from the flowers of the Georgetown gardens — what is in bloom at this time of year? The same season that the uprising started back in August 1823. I want to cross the bridges over the canals that run through the town. I want to walk up the steps of the old red-and-white striped lighthouse, and take in the expansive panorama from the top. Is it really possible to see into the fort where some of the rebels were so viciously flogged? I want to feel the dirt of the muddy river bank between my toes. Is it cold? Is it sticky? Is it slimy? I want to begin to understand the geography of the land, how the shore meets the bush and the savannahs and the mountains.

I want to know how you get from the airport to the city centre. What do the billboards read? When is the traffic busiest? From pictures online, I see that the streets are now filled with busses and bikes and trucks, but how does it sound? And how many of the old buildings are still in place?

I want to see the sunset – if you stand outside St Andrews Church where would the brightest colours be and what colours would you see? And I want to know how quickly the darkness falls after the gloaming. Instead, I am sitting at my desk, looking at the grey sky, imagining and almost certainly getting it all wrong.

I want to visit the monument for the 1823 rebellion by the sea wall. I want to see the Bethel Chapel where John Smith gave his sermons and stand for a moment near the entrance to Success at the main road where the body of Quamina was so cruelly hung. I want to visit Colony House — does it still exist? — where the trials took place after the insurrection. But, for now, I can’t.

For now, all I can do is read the historical documents that I find online, look for the answers against the official grain.

So I take another ginger biscuit and dream of the things I cannot for the moment do.

I want to meet people who study the history of Guyana, their history, our connected histories. I have questions which are probably basic to others, but with which I struggle. This is all new to me, and I come with great humility. What I know is how little I know.

In the 1820s, for instance, what did the inmates at New Gaol wear? What did they eat? How many people were crammed into the cells? What did the prison look like?

Here’s another one. Where did Jack Gladstone — one of the leaders of the insurrection — go the following year? The governor at the time said he was to be deported to Bermuda, but that’s a long way to go. A Brazilian historian wrote that Jack Gladstone was actually sent to St Lucia, but nobody there can find a trace of him. Where does the truth reside? How did this Guyana hero spend his last days and where?

There are more questions! What role did women have in the 1823 insurrection? There is little mention of them in the official records, but perhaps their stories have been passed down the generations.

Most of all, I want to meet and chat with people in Guyana. And ask what does the 1823 Insurrection mean to you, to the country, today? I wonder, for instance, are there any Gladstones still living in Guyana and would it be possible to meet them?

Which is why I so want to visit, but I can’t. I have to wait. So I go downstairs again and finish the last biscuit. Did I really eat them all?

When I was growing up, my two grandfathers gave me contradictory advice. My mother’s father said ‘If you don’t ask you don’t get.’ My dad’s father, who thought I was too fidgety and energetic, said ‘Sit on your hands’. So I will try and be patient, I tell myself, but I will also ask for help.

All that to say, if you have anything you wish to share with me, please get in touch at 1823@thomasharding.com. Thank you. Hoping to see you all soon.