By Stanley Greaves

Al Creighton’s admirable and very informative recent article on the late George Simon served as a further reminder to me of the absence of publications on the lives of Guyanese who over the ages have made significant contributions to Guyana in many fields of endeavour that add to the cultural development of the land. The term cultural is sometimes taken to mean presentations in the field of the creative arts, but it is in effect an all-inclusive term relating to all possible activities, ranging from the use of language to funerals.

In the 1970s Arthur Seymour, a director within the Department of Culture, began to prepare biographies of eminent Guyanese. I made a suggestion to him that it was a great opportunity to establish a collection of portraits of the same individuals as the beginning of a National Portrait Gallery because at the same time Emerson Samuels, a very fine portrait painter, was producing graphics for government departments. My suggestion was dismissed with a smile that spoke more loudly than words.

There is biographical information online about Guyanese individuals of merit but many more remain undocumented. In any event, the information should be in books to be studied in educational institutions. Art is my area of interest and it would have been great to have biographies published on the lives of the pioneers in art of the 1930s and those who followed and are now no longer with us, including Edward R. Burrowes, Hubert Moshett, Marjorie Broodhagen, Stephanie Correia, Cletus Henriques, Donald Locke, and Ronald Savory. Special mention must be made of Hubert Basil Hinds, who reported diligently on the Arts, with emphasis on the Visual Arts, in weekly Sunday papers and other publications, like literary magazine Kyk-Over-Al. He was the first and last to write on a consistent basis. No other person has stepped forward to continue this work. A while ago, Akima McPherson and I attempted to create interest by writing on artists and their works in the National Collection for about a year. The challenge to others is to extend the commentary and include present practices and achievements. The absence of publications on artists of the Caribbean was a significant hindrance to my own development. I had to look elsewhere and trust my intuition to guide me as to what to accept conditionally and what to reject.

In Guyana, there seems to be reluctance to research and publish biographies.

I am sure information can be found in the National Archives, and in the National and University of Guyana libraries. Also available would be institutional records, local, regional and international, private book collections, personal papers and finally what has already been documented online. I am painfully aware that a wide range of memories of personal, familial, professional and national events retained by individuals die with them. The Linguistics Department of the University of Guyana in the 1970s investigated African retentions in our use of Creolese and even Standard English. Unlike traditional societies in West Africa, we did not have griots – the memory banks of tribes who in the absence of written records were trained to memorise the detailed history of the clan and or tribe.

At one time in Guyana, the now defunct Argosy newspapers did publish works by local writers and researchers on various themes. The demise of the recent Caribbean Press and its publications on Guyana is totally regrettable. Among the Anglo-Caribbean nations, it was without precedent and unquestionably should be resuscitated for circulation at all levels, from the individual to the institutional.

At one time in Guyana, the now defunct Argosy newspapers did publish works by local writers and researchers on various themes. The demise of the recent Caribbean Press and its publications on Guyana is totally regrettable. Among the Anglo-Caribbean nations, it was without precedent and unquestionably should be resuscitated for circulation at all levels, from the individual to the institutional.

Our society is perhaps too small to support professional biographers and this is where the University of Guyana comes in. A publication unit has recently been formed with links to Jamaican publishers Ian Randle. Around 1977, Professor Bill Carr, then Dean of the Faculty of Arts, and I did make an attempt to establish such a unit and failed because of the financial crisis that was facing the nation and which inhibited development in all quarters. Is it too much now to ask faculty members and graduate students to engage in research on an individual or collaborative basis to produce biographies for publication? I go further to suggest that such publications should form part of required reading in all educational institutions. There is no doubt about the incentive this would create by encouraging others to identify with our own creative nationals in all fields and to develop their own potential and, by extension, that of the Nation as well.

To diverge somewhat, there was a time in the 1970s when the Ministry of Education had set up a publishing unit under the direction Agnes Jones, a most dedicated educationalist, to produce reading books for Primary Schools. The texts were written locally and illustrated by graphic artists. I was even in charge of training a team of four in graphic techniques. Each text that was published could be considered a pseudo biography because the themes were about the lives of children from different regions in Guyana. It was a production that did not exist anywhere else in the Anglo-Caribbean. The impact created was instantaneous because children easily identified with what related to their own experiences and also learned about the parallel experiences of others. The production was, however, discontinued.

Exemplars

A final observation along these lines is about the life and work of a local civil engineer, who made use of an incredible natural gift. I only knew him as Mr Poole. I once asked one of his employees what contributed to his reputation. I was told that on a work site he was never to be found in his office but was always at the different points of an operation, more often than not in a pit in order to calculate the ratio of cement mixtures needed for a particular location by actually tasting a sample of the soil and testing the texture using his fingers — no formulas from books, no special machine for analysis. He was a living exemplar of the unity of intuition and intellect. What a gift his knowledge would be to soil scientists. His understanding of the Guyana environment was the foundation of his work as an engineer. A foreign company was once commissioned to build a riverside construction somewhere around the estuary of the Berbice River. He stated that the location of the construction was wrong and it would be destroyed by the tides. It happened as he predicted and he was then given the contract, which was completed satisfactorily. It is most regrettable that after retirement he was murdered in his East Coast home by an intruder.

I would see him sometimes in Georgetown, always in Camp Street near Middle. The shop at that location belonged to the family. He would be dressed in a khaki suit, wearing an out of shape felt hat and wire rimmed spectacles, riding an old bicycle with his trousers clipped at the bottom, a most unprepossessing figure. Imagine what his biography would mean to an aspiring civil engineer. The official title of ‘Living National Treasure’ would have certainly been his had he lived in Japan and he would have been expected to pass on his experiences and expertise to others. There are a number of such individuals in the past in Guyana who would have been deserving of the same title, and no doubt some do exist now as well. I leave it to the imagination to consider what the publication of biographies would do to young ambitious minds.

Over a shared fence

Finally, Creighton did mention my name as engaging with the works of writers Martin Carter, Wilson Harris and Edgar Mittelholzer. This took place primarily as a felt need to respond to works of others in the Creative Arts. I know that in Guyana there was little or no significant dialogue taking place between writers and artists. In 1985, the Vice-Rector of the Cuban Superior Institute of Art visited Guyana to do research on Guyanese Art. Among the first questions asked was,

‘Where do Guyanese artists and writers meet?’

‘They do not’.

‘I have seen references in catalogues.’

‘That’s only on the occasion of an exhibition.’

I was well aware from reading that meetings and exchanges between the two groups were common occurrences in Latin American and European countries. In Guyana, no such meetings took place. It is as if we were oblivious of each other’s existence. Our two major novelists in the UK, Mittelholzer and Harris, did include artists in their works, hence the attention I paid to their novels. In any event, more attention was given to the written word, as evidenced by Seymour’s publication of Kyk-Over-Al, than to the Visual Arts. At Christmas. Basil Hinds would review exhibitions in the Chronicle Christmas Annual. It did not improve attendance at exhibitions. Art was not an important area of study in schools that would have created a discerning public. The situation still exists.

Unfortunately, I was the only artist who took time to engage with Carter; not only with his writing but in conversations as well for several years. I responded to the metaphysical implications of his later poems, which eventually related directly to what I was doing in the 1990s series of small 9.5 inch x 10 inch paintings, the Mini Series numbering 155 and continuing. I also illustrated his poems in two publications. One was a small collection published by Raman Mandal at the University of Guyana and the other was the revised edition of Carter’s Selected Poems, published by Red Thread Women’s Press.

I have also read and illustrated poems by Ian McDonald, which in my estimation are more metaphysical than lyrically descriptive.

In Mittleholzer’s case, I was quite impressed by his inclusion of artists in his novels and even gave a talk at UG on this topic. Of particular interest was the novel Shadows Move Among Them, which involved an Indigenous artist whose work presaged that of George Simon. I was therefore most impressed when Simon arrived on the scene and eventually created a body of work relating to Indigenous culture that went beyond marginal works by Marjorie Broodhagen and also supplemented the mythological themes in Stephanie Correia’s works.

I did not illustrate any of Mittleholzers’ novels but Shadows Move Among Them did reflect a particular interest of mine — the existence of shadows. It led to the appropriation of the title for three series of paintings where shadows revealed the pursuits of individuals who were not present. The shadow was the presence.

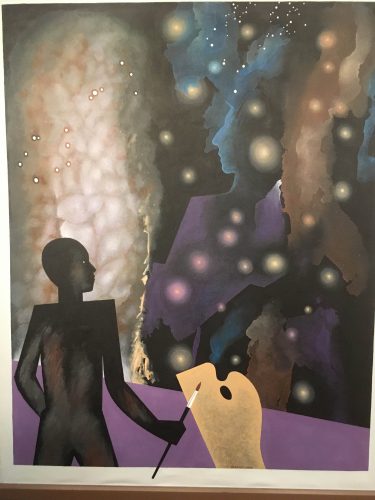

In Harris’s case, I tried to relate his experiences in the hinterland with some of mine. The title of the series, Dialogue With Wilson Harris, reflects this intention. Anyone reading Harris would know that it is impossible to attempt to illustrate his works. In discussing my project with him, he remarked, “I wish you well,” and was most supportive later after seeing what I did – 24 paintings from reading too many novels from 2011 to 2014. I did make an early attempt in 1966 and gave up after two paintings, but the project was so important it remained simmering for decades in my mind.

The appearance of artist characters in so many novels remains a signal achievement for both Mittelholzer and Harris in the absence today of any such body of work by Anglo-Caribbean writers. I leave with questions: where today are the writers following the footsteps of that inimitable duo? And how many artists are attempting to relate to the works of writers? Therese Hadchity, of the now defunct Zemicon Gallery in Barbados, did make an attempt to have artists produce paintings based on the works of writers. It did not create a sustained interest. At individual and collective levels, the groups as neighbours still view each other over a shared fence—the Arts.