In early February, while attending the Commonwealth Writers’ Workshop at Moray House, I was introduced to Nalo Hopkinson’s work. Our workshop facilitator advised me to explore Hopkinson’s work because of my interest in writing Caribbean speculative fiction: a literary genre of writing that covers hard sci-fi to high fantasy and everything in-between, but which is based on Caribbean life and contexts. At the time, I had no idea what speculative fiction was, and I was most certainly woefully underinformed about the Caribbean’s rich contributions to the genre.

So, when the pandemic hit and I found myself trapped indoors and struggling to complete my degree while being creative, I did the only thing that would comfort me: I retreated into books, starting with Hopkinson’s work. Soon enough, I began to fall in love with her writing.

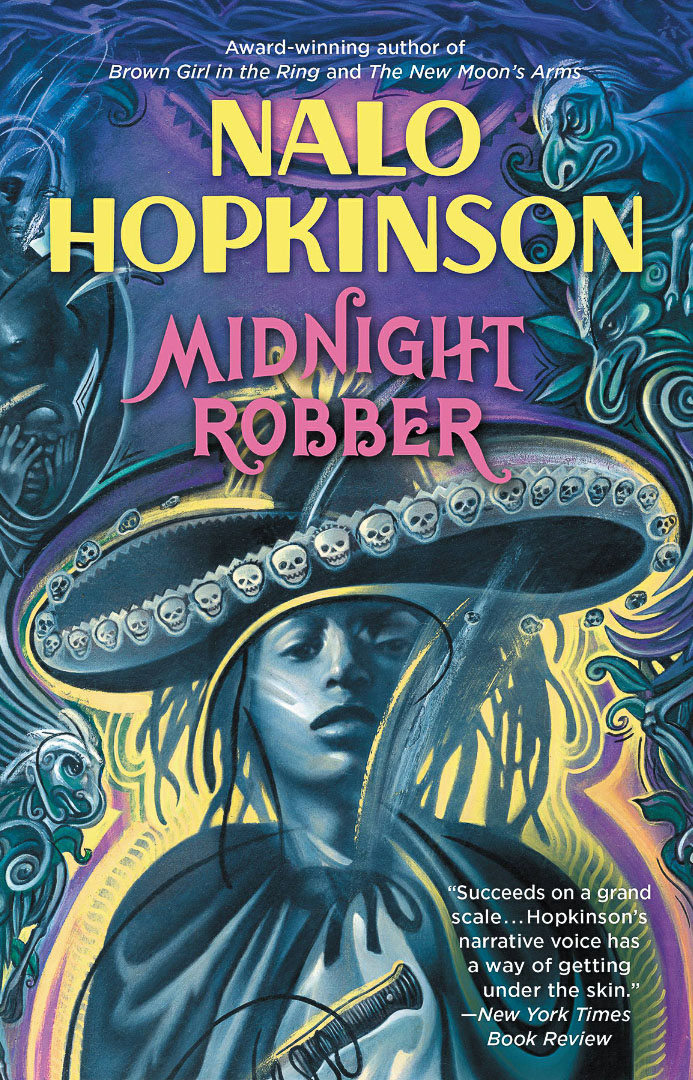

So far, I have read five of Hopkinson’s books. I started with her short story collections Skin Folk (2001) and Falling in Love with Hominids (2015), which acted as a teaser for Hopkinson’s novels, which were much heavier and complex. I read The Salt Roads (2003) on my own, and her debut Brown Girl in the Ring (1998) as a part of my yearly book club readings. My favourite book thus far, however, is her second novel: Midnight Robber (2000).

“But wait—you mean you never hear of New Half-Way Tree, the planet of the lost people? You never wonder where them all does go, the drifters, the ragamuffins-them, the ones who think the world must be have something better for them, if them could only find which part it is? … Well master, the Nation Worlds does ship them all to New Half-Way Tree, the mirror planet of Toussaint. Yes, man; on the next side of a dimension veil.” (p. 2).

Midnight Robber follows the misadventures of a young girl named Tan-Tan, who was born on Planet Toussaint, a Caribbean space colony. There, as the daughter of Mayor Antonio of Cockpit County, she lives a life of relative luxury as her personal nurse, the house eshu, and her robot minder take care of her and shield her as best as they can from her parents’ personal drama.

When her parents’ drama explodes into the public, and her father commits an unforgivable crime, she and he escape across a dimension veil to the prison planet called New Halfway Tree covered by an unforgiving forest called the diable (devil) bush. There, the monstrous creatures from Toussaint’s Carnival and folk stories are no longer playful masquerades, and the people are just as dangerous.

To survive in this brutal vagabonds’ land and endure her personal traumas, Tan-Tan must fully embrace the spirit of her favourite Carnival character, the Midnight Robber. Only by becoming the Robber Queen and forming unlikely friendships with strange creatures is she able to survive her traumas and go on a journey of self-discovery, acceptance and healing.

“Back-break not for people,” Tan-Tan quoted at her scornfully.

“We not people no more. We is exiles. Is work hard or dead.” (p. 135).

The thing that captivated me the most about Hopkinson’s work was her worldbuilding. Before reading Midnight Robber, I had never read a sci-fi novel by an author of Caribbean heritage. Hopkinson’s father, I later found out, was an actor and poet from New Amsterdam. She was born in Jamaica but grew up in Guyana and Trinidad as well before her family moved to Canada. This added a whole new layer of context and intimacy to her work.

These Caribbean elements are spread out through both Planet Toussaint and New Halfway Tree. The novel starts just before Jonkanoo Season on Toussaint, and the Carnival-like aspects of this season blend Jamaican, Guyanese and Trinidadian traditions and folklore. People wear jumbie leather sandals, and calypsonians sing about political scandals in hopes of becoming Road March King or Queen, and people just generally have fun in the street. Even the police of Toussaint don’t seem to want to be bothered with work during the season because, as they say, “we hear the jump-up sweet down in the city”.

New Half-Way Tree is how Toussaint planet did look before the Marryshow Corporation sink them Earth Engine Number 127 down into it like God entering he woman; plunging into the womb of soil to impregnate the planet with the seed of Granny Nanny. (p. 2)

The technology on Toussaint is also infused with Caribbean elements. There are house eshus (sassier versions of Alexa or Siri), robot servants with bodies coated in chicle – the gum that leaks from the sapodilla plant, and self-driving smart cars. The thing that controls all this tech, while still caring for the individual people of Toussaint, is a benevolent overarching AI: the Grande Nanotech Sentient Interface, which the locals called Granny Nanny after the Jamaican maroon leader.

Conversely, New Halfway Tree feels more like a grittier version of Pandora from James Cameron’s Avatar, though Midnight Robber predates it by nine years. On New Halfway Tree, there is a native sentient species who live in massive banyan-like trees called Daddy Trees or Papa Bois, which reminded me a lot of the Home Tree from Avatar. These people, the Douen, live, work and play in the bows of the Daddy Tree high above the dangers that lie below. One of them, Chichibud, becomes one of Tan-Tan’s closest allies.

I am amazed by the way Hopkinson uses folklore and folksongs from Guyana, Trinidad and Jamaica to build her world, make characters and add tension to scenes. The one example I hold dear is Nalo’s use of the Guyanese folksong Itanami at a critical point in the story. I remember having to put the book down and just stare off into space because I never saw a Guyanese folksong used in Sci-Fi before. This, I know, is the moment that I fell in love with Hopkinson’s work.

“Oho. Like it starting, oui? Don’t be frightened, sweetness; is for the best. I go be with you the whole time. Trust me and let me distract you little bit with one anansi story…” (p. 1).

While I may gush about Hopkinson’s worldbuilding and the way she includes folklore and folksongs into her work, I must admit that Midnight Robber was a very emotional read, especially in the middle of a pandemic. The book tackled serious issues, such as the way children cope with emotionally unavailable parents, child abuse, sexual abuse, ableism, the hypersexualization of girl children, loneliness and depression. We explore Tan-Tan’s traumas through the main stories, yes, but between each chapter is an Anansi story that delves deeper into Tan-Tan’s psyche with a story style that seems reminiscent of Caribbean oral storytelling tradition. There, Hopkinson presents truth wrapped in metaphor and coated in sweet words to indirectly ease us into the darkest parts of the story.

In this way, Hopkinson ensured that Midnight Robber was not trauma porn. She showed us the way individuals and society hurt Tan-Tan, yes, but she also showed the reader the people who tried to get her out of her bad situations, the ones who helped to show her the path to healing as she struggled to find peace.

But most importantly, she shows us Tan-Tan’s path to healing, getting help and forgiving herself after she comes to terms with what has happened to her, and understands that she was not responsible for her situation nor her pain. I admire Hopkinson for presenting Tan-Tan’s story with grace and empathy, while also immersing us into this bizarre futuristic fantasy world that seems like it was written last year rather than 20 years ago. In my opinion, Midnight Robber should get a lot more attention, especially since it stands the test of time.

Midnight Robber is one of the best books that I have read since I started social distancing in March. Even with its darker themes around pain and isolation, this book gave me so much joy and comfort. My only critique is that I genuinely wish that Hopkinson had done more with some of the plots that she set up on the Toussaint side of the story. A friend of mine, with whom I buddy read Midnight Robber, confessed that she wished she could get a series of short stories that were set in both Toussaint and New Halfway Tree because of how fascinating the worlds are, and how boundless they feel. I agree with her, and I hope that one day Hopkinson may revisit these worlds and let us have just a little more of Tan-Tan and the twin worlds she called her home.

Nevertheless, even without this expansion pack, Midnight Robber holds its own as one of the best stories I have read this year, and I will keep it as one of my favourite novels. If you’re looking to explore Caribbean Sci-Fi, Midnight Robber is a great starting point. It will amaze you, sadden you and anger you. But, at the end of it all, you will want to read more of her work and the Caribbean’s rich contributions to the sci-fi and fantasy genre.

Nikita Blair is a speculative fiction and creative non-fiction writer. Her work has been featured in Moray House’s Ku’wai magazine, The Guyana Annual, the Stabroek Weekend’s Writers’ Room and the Commonwealth Writer’s blog. A collection of her work is featured on her blog, blairviews, where she writes book reviews, essays, and articles on topics of interest. Currently, she is completing her degree in Communications Studies at the University of Guyana, Turkeyen.