(SciDev.Net) – Developing countries that have been pushing for stronger ecosystems protections have been armed with a cache of evidence, released in a series of biodiversity report cards that warn the world teeters at a crossroads.

Urgent action is needed to protect food systems and health and mitigate climate change, says the United Nation’s latest Global Biodiversity Outlook, published today. Assessing the progress against the 20 global biodiversity targets agreed in 2010, the report reveals just six targets were achieved — and only partially — by their 2020 deadline.

Biodiversity — the variety of plants, animals and all living things on earth — is being degraded by pollution, overfishing, and increased use of forest land for agriculture, says the report, published every five years by the UN Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD).

While up to US$90 billion for biodiversity protection was available in the past decade via national governments and development assistance, biodiversity finance needs are “conservatively estimated in the hundreds of billions of dollars”, says the outlook.

“Moreover, these resources are swamped by support for activities harmful to biodiversity,” the report says. This includes $500 billion in fossil fuel and other subsidies, $100 billion of which related to agriculture.

In Brazil and Indonesia alone, subsidies for the production of commodities linked to forest destruction were estimated in 2015 to be 100 times larger than the amount spent combatting deforestation, the report found.

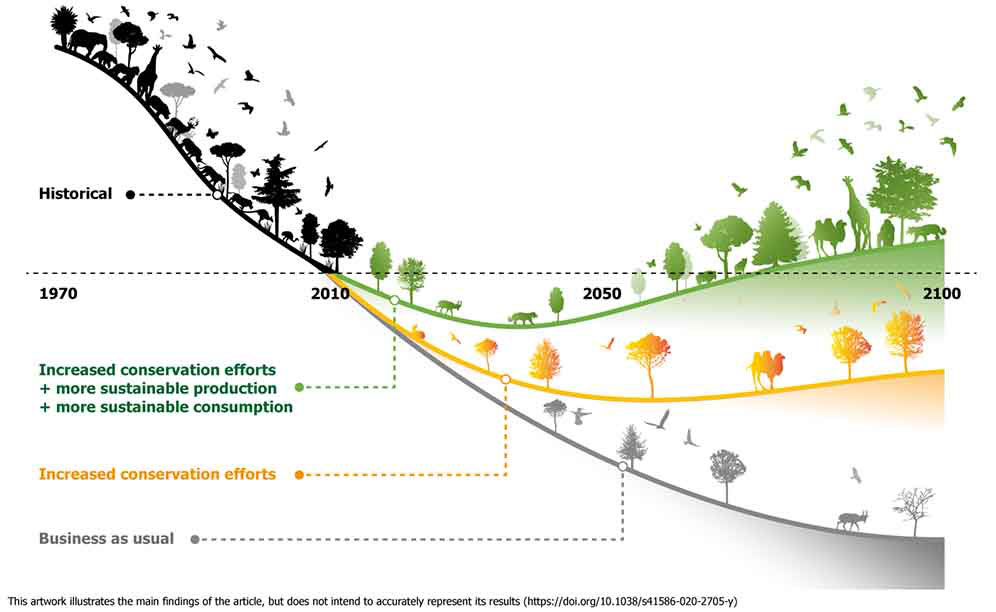

The WWF’s Living Planet Report 2020, released last week ahead of the UN’s biodiversity report card, reveals that the size of the world’s wildlife populations shrank by an average 68 per cent between 1970 and 2016.

Christopher Trisos, senior research fellow at the African Climate and Development Initiative at the University of Cape Town, tells SciDev.Net that such analyses can help arm policymakers and governments in the global South with the evidence needed to protect their local ecosystems.

“In the context of climate negotiations, global South countries have been some of, if not the strongest, advocates for lowering global emissions,” he says. “Reports like this give them the information and reasoning to negotiate their positions.”

National governments are currently negotiating a new 10-year global framework for biodiversity policy-making.

The new goals must recognise the contributions of indigenous peoples and local communities in protecting ecosystems, say the CBD’s Local Biodiversity Outlooks, which will launch tomorrow. The world’s failure to recognise traditional and local knowledge is directly linked to the global failure to meet the 2020 biodiversity targets, the local outlook argues.

Reversing the trend

Changes to food systems and stronger environmental protections could stabilise losses, says new research published in the journal Nature, which formed part of the WWF report.

“Pioneering” modelling produced a ‘proof of concept’ that the world can halt, and reverse, biodiversity loss from land-use change, say researchers.

“Through further sustainable intensification and trade, reduced food waste and more plant-based human diets, more than two thirds of future biodiversity losses are avoided and the biodiversity trends from habitat conversion are reversed by 2050 for almost all of the models,” says the team of researchers, led by David Leclère from the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

“[A]mbitious conservation efforts and food system transformation are central to an effective post-2020 biodiversity strategy.”

This is in line with the shift from ‘business as usual’ described in the UN outlook, which gives eight urgent transitions for reducing the negative impacts of human activity. Pointing to the unprecedented global response to COVID-19, the UN report says efforts to address land and forest degradation are achievable.

“The response of governments and people around the world has demonstrated society’s capacity to take previously unimaginable steps, involving huge transformations, solidarity and multilateral effort in the face of an urgent common threat,” it says.

Trisos says the UN outlook comes at a critical moment. “Now is the time for governments to invest in tech policies and social actions that are positive for people and nature as part of the COVID-19 recovery trajectory,” he says.

Responses to biodiversity loss should be based on data, which is scarce in Africa and parts of the global South, says Beth Kaplin, acting director of the Centre of Excellence in Biodiversity and Natural Resource Management at the University of Rwanda.

“[W]e need data to know what is working, what isn’t and where to adapt,” she tells SciDev.Net. “This emphasises the importance of building research capacity and the capacity to link science to policy.”

The UN Summit on Biodiversity will convene at the General Assembly on 30 September to discuss urgent action on biodiversity for sustainable development.