During September, celebrated as the Indigenous Heritage month in Guyana, we are paying another visit to the unfathomable depths of Guyanese Amerindian literature. Last week we revisited the oral literature. This week we examine the drama and ask the question: why has there been so little? The output in theatre has not come anywhere near the inexhaustible volumes in oral literature, fiction, and poetry.

During September, celebrated as the Indigenous Heritage month in Guyana, we are paying another visit to the unfathomable depths of Guyanese Amerindian literature. Last week we revisited the oral literature. This week we examine the drama and ask the question: why has there been so little? The output in theatre has not come anywhere near the inexhaustible volumes in oral literature, fiction, and poetry.

As a branch of literature, drama has essential characteristics that set it off in its own category. It is written for performance on stage. It is theatre which demands performance and throughout history most of what may have been practiced has not survived. Right across the Caribbean there is little trace of pre-Colombian theatre, and records of performance in the early centuries of European colonisation have not done much better.

In Guyana we get a sense of ancient performance traditions which were mostly linked to the spiritual in a few traditional dances. What is performed by the Surama cultural group led by Glendon Allicock may provide a few examples. But if we are to try to go further back in time, perhaps the best picture is provided by Audrey Butt-Colson an anthropological researcher. Butt-Colson, formerly of University of Oxford, was also associated with the Amerindian Research Unit at the University of Guyana (UG) and as a modern anthropologist produces studies significantly different from most of her colonial predecessors in the field. In this respect, she is similar to historian Mary Noel Menezes, Professor Emerita of UG, who was able to distance herself critically from the colonial researchers.

While Walter Roth and William Hillhouse, for example, were, like most of their colleagues, highly skeptical, dismissive, and uncharitable towards some cultural traditions and characters in Amerindian beliefs, Butt-Colson was much more understanding. Through her accounts we can appreciate the theatrical performances of the shaman and piaiman in indigenous societies. Her analyses tell us quite a bit about what the ancient theatrical acts were like, tied as they were to the spiritual.

Moving closer to the contemporary, there are accounts of stage performances of material taken from Amerindian mythology and legend, particularly the heroic variety. Stanley Greaves, for example, in dialogue with Mark McWatt, writes about the legend of Amalivaca:

Greaves: “Dancer Helen Taitt once produced a dance theatre show by that name at Queen’s College. She was principal dancer as well. I did the stage design. The overture was a composition by one of the Pilgrim brothers from that musical family. The poetry of A J Seymour is not mentioned these days… as is Wilson Harris’ poems written in Guyana. Mahadai Das was also an exceptional poet hardly if ever quoted. All I can say is that poetry always had a very limited following.

McWatt: “I remember hearing about the show ‘Amalivaca’, but never saw it… Perhaps when Guyanese get over the racial/political turmoil and all the corruption and can think of poetry and the arts again Seymour and Mahadai Das and others will be read and treasured again…”

While they reference the poem “Amalivaca” by Seymour, the importance there is the dramatic performance. Helen Taitt, legendary dancer, did write drama and performed them with her dance group at the former Woodbine House or Taitt House (now the Cara Lodge Hotel). At least one, “Amalivaca”, was taken from the Amerindian heritage.

There was another that is much better remembered. “The Legend of Kaieteur” based on the poem by Seymour, was put to music by Phillip Pilgrim, one of the “brothers from that musical family” and performed on a number of grand theatrical occasions by the Woodside Choir or some other national ensemble. That has thus been a major contributor of the indigenous heritage to dramatic performance in the nation.

When it comes to the writing of major plays in a more direct way the examples are few. Taitt’s “Amalivaca” was more in that line than “The Legend of Kaieteur” since it was a musical with dance and drama. But since then in the post-independence period these plays amount to a mere handful.

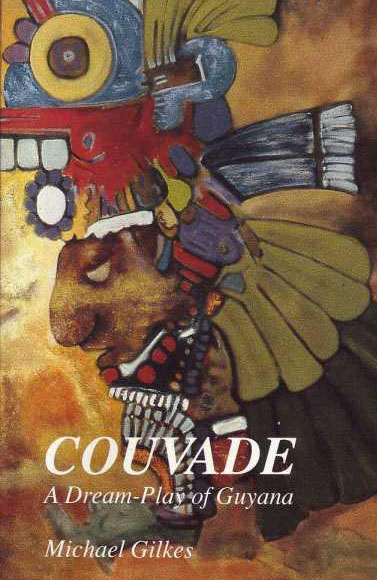

Yet, they number among them powerful pieces of theatre that are monuments in national drama. They are telling contributions. The foremost of these, most celebrated and revered is Couvade by Michael Gilkes, first performed in 1972, published in print form in 1974 with a reprint in 1991, then revised and published by Peepal Tree Press in 2014. Couvade, which has a sub-title A Dream Play of Guyana, remains one of the country’s foremost plays of any type by any playwright. It is based on an Amerindian tradition or belief known as couvade. This custom was first identified by an anthropologist in 1865 and has been associated with many different cultures around the world. But it is named as a custom of the Caribs and other nations in Guyana. Certainly, Gilkes’ play draws on Amerindian traditions in its use of couvade.

In this custom, normally healthy men undergo sympathetic symptoms and behaviours during the time when their wives or partners are pregnant, close to the time of delivery or during labour. The man will take to his bed as if he is suffering or ill and simulate the birth experiences of the woman. Among other things, it is said to be a way of diverting malignant spirits away from the woman and child.

Jeremy Poynting describes the drama in this way:

“On one realistic but symbolic level, Lionel’s wife Pat is in the latest stages of her pregnancy, whilst in her view her artist husband has become obsessed with the Amerindian-themed painting he is working on, to the detriment of his concern for her. At another ritual level in the drama, apparent only to Lionel in his dreams, a shaman enacts a collective ritual of offering and celebration of the gods. As Wilson Harris, who wrote the introduction to the second publication of the play (“a play I much admire”) observes, Lionel appears overwhelmed by forces from the past, a confrontation with a broken heritage that the play suggests the Caribbean artist must make.”

Gilkes employs the Amerindian heritage in this way in a play that treats healing and race. The artist has a responsibility here, very much as Edgar Mittelholzer gives him that responsibility, particularly in such a novel as My Bones and My Flute. The artist appears again in a not dissimilar role in a later play by Gilkes, A Pleasant Career, about the life of Mittelholzer. Gilkes writes about Guyana, which is a racially fractured society, and in the play the Amerindian shaman appears in a dream to Lionel to invoke the gods in achieving healing. Simultaneously, the artist protagonist is working on an Amerindian painting which, symbolically, will achieve the same spiritual outcome.

The other major play of note is very much contemporary Guyanese drama, although not nearly as widely known as Couvade and is by a new dramatist, yet to reach Gilkes’ level of establishment. Masque by Subraj Singh was first written and performed in 2016. It is highly decorated, having swept the prizes in the 2016 National Drama Festival and thereafter, was selected to represent Guyana as the signal drama piece in Carifesta XIII in Barbados. It was performed by the National Drama Company, of which Singh is a member, and stood out among the plays seen in Carifesta.

Singh has already accumulated an impressive collection of decorations. His entry into drama after graduating in English from the UG, saw him emerge with the prize as the Best Student in the Institute of Creative Arts in 2015. He earned the Diploma in Drama with a perfect GPA of 4.0. He repeated those feats in 2018 when he completed a Diploma in Creative Writing. Singh’s achievements were recorded at the highest national and regional levels. He was short-listed for the Award for Developing Writers among the OCM Bocas Literary Prizes in 2018 and won the Guyana Prize for Literature for the Best First Book of Fiction in 2014. He has won other prizes as well as fellowships and the benefits of international workshops in creative writing. He is a product of the National School of Theatre Arts and Drama where he now serves as a lecturer.

Masque is a play distinguished for its bold risk-taking excursions into post-modernism in techniques of writing and staging. It is a post-colonial play about the historical experiences of the ancient Guyana Amerindians and the effects those have had on the people’s prospects for the future. It contextualizes colonisation and the scars of genocide in a history of violence, conquest, and vengeance.

Masque is a Senecan Revenge tragedy in a form of post-colonialism. The spirit of Rhoda, the wife of an Amerindian Chief murdered by invading Europeans, returns as an agent provocateur, a force urging her people to pursue a fierce path of revenge against Europeans. It turns out to be a savage internal struggle between the Chief’s son and heir, who has learnt wisdom and compassion and his sister, who has inherited the hatred and single-minded hunt for vengeance from the spirit of her slaughtered mother. But the British invaders are unrepentant in the person of Lady Radcliff and the poisoned mind of her daughter. Lady Radcliff becomes the lover of the Chief’s son for the expressed purpose of leading the invaders into the village once again.

The play is characterised by excessive violence to highlight a theme and covenant in the history of relations between the ancient nations and the European conquerors. But it also expresses a concern for the environment and its destruction which has been both literal and symbolic. It links environmental destruction with human plunder and a wiping away of a people from the face of the land in the future.

This drama tackles racism, tradition, healing and has a feminist outlook, reading history from a post-colonial standpoint. It takes a very critical look at indigenous culture, the survival of traditions and their place in an independent Guyana. It is rare in its critical treatment – just as rare as the emergence of major plays that treat with Amerindian heritage in Guyana.