Throughout history, tales of the Indies were often as romantic and sensationally exotic in appeal as they were superficial, but today playwrights produce work of more depth. The contrast is vividly displayed in the dramas referred to below.

Throughout history, tales of the Indies were often as romantic and sensationally exotic in appeal as they were superficial, but today playwrights produce work of more depth. The contrast is vividly displayed in the dramas referred to below.

Walter Ralegh, who, incidentally, was a poet as well as a courtier, set the stage in 1597 with the thirst for El Dorado. Although practically nothing of the theatrical traditions that went before him, and before Columbus, has survived, his very dramatic intervention left a histrionic platform for the imagination which has had infinite rehearsals in literature ever since. The obsession with gold and the legend of a gilded prince possessed not only Ralegh, but Caribbean literature up to the present time.

Yet the possession was not always charged with the richness often seen today, but experienced along the line, an obsession with fantasy and exoticism. For instance, Errol Hill cites plays in or about Jamaica in the early period of the 20th century which read as though the writers “had never set foot in Jamaica”. One example is San Gloria, which like some others exploits fantastic tales about the Arawaks and about Columbus’s arrival. There are other yarns spun by writers with indeed little knowledge of their subjects.

Several decades later, in more modern times the annual Jamaica Pantomime musical was Hail Columbus; this was in the 1970s. It was much better informed than its precursors of half a century earlier. By the time Hail Columbus was performed, drama was much more effectively influenced by knowledge of history, even though it was still based on lore. Pantomimes thrive on humour and on folklore as much as they do on satire. Hail Columbus was as worthy a work as you could get from its type about Amerindians, once that country’s first people, who no longer live on the island and are only known to Jamaicans through history and myth. At that time, too, despite the comedy, the post-colonial treatment of such a subject as the arrival of Columbus made it a drama of a vastly different nature.

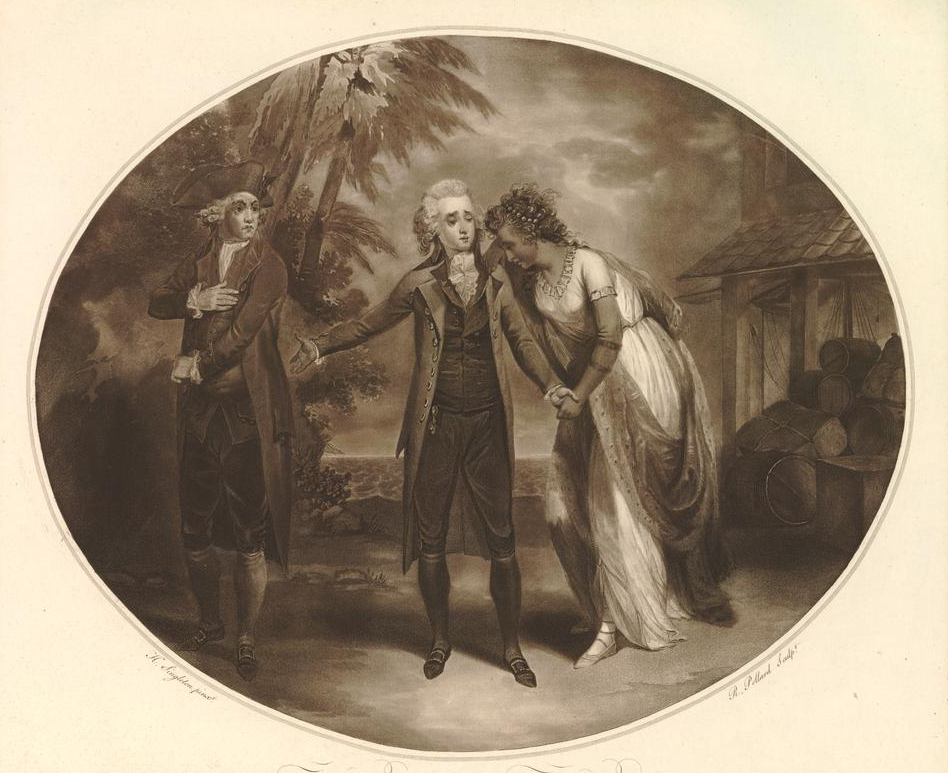

One of the more famous plays in the history of West Indian drama is Inkle and Yarico, an opera first performed with untold success in London in 1787. It was drawn from a story that originated in Barbados and first published by Richard Ligon in 1673. It was then made more famous by Richard Steele who heard it from another source and published it in The Spectator in London in 1711. It was said to be the true story of a young English trader, Thomas Inkle, who was shipwrecked on a West Indian island. While his companions were captured and some killed by the native inhabitants, Inkle was rescued by an Amerindian girl who hid him from her countrymen and restored him to full health. They fell in love and lived secretly together until rescued by an English ship. Upon arrival in Barbados Inkle promptly sold Yarico into slavery. The story is also told in a novel, Inkle and Yarico by Guyanese novelist Beryl Gilroy.

While this sounds like a tragic tale as Steele told it, the London performance was an opera. In those days that was a comic drama with music, often with a romantic core. Of course, in the hands of superior playwrights like John Gay, plays of great depth were created out of that genre. But this was never one of those; the interest in that tale soon became one of popular appeal. The comic opera’s success inspired many others and several versions of the play were translated, published, and performed in countries across Europe. But it was not a subject taken seriously by dramatists or audiences, not even as a sensational romantic drama. For them, a story about a wronged, exploited Amerindian woman was not tragic material, but good as a superficial comedy.

In contemporary Guyanese drama, the plays are quite different in type and orientation. Among the few of these that exist is one that has made a significant mark, A Fair Maid’s Tale, (2004) by Paloma Mohamed. Not only is it distinguished by being among the few existing Amerindian plays, but by being very much in demand.

Mohamed herself is highly celebrated with a number of significant distinctions. As the new Head of the University of Guyana (UG), she is among a very few Vice-Chancellors in the Caribbean who have been artists of note. That puts her in very noble company. The University of the West Indies has had two. The first was Sir Philip Sherlock who was a prominent Jamaican poet as well as historian and folklorist, who opened the Creative Arts Centre on the Mona Campus which was later named after him. The second was the most distinguished Rex Nettleford, dancer extraordinaire, founder and director of the famous National Dance Theatre Company and a legend in culture, the arts, and scholarship.

UG’s first was Dennis Craig, a prominent Guyanese poet who won Best First Book of Poetry in the Guyana Prize and one whose work has been extensively anthologised. Mohamed is the second. She is a foremost Guyanese playwright and multiple winner of the Guyana Prize for Drama with a record of several successful award winning productions on the Guyanese stage as writer and director. She has been able to claim a place in popular theatre with best-selling comedies as well as plays of formal, social, and thematic seriousness. At the national level, she has claimed prizes as an actress and singer, and is Chairman of the Theatre Guild of Guyana.

Another of Mohamed’s crowning achievements is the Anthony N Sabga Caribbean Award for Excellence for her work in Arts and Letters. She has published collections of poetry and of plays, including what is perhaps her most accomplished play, Duenne, published by the Caribbean Press and often performed. Her Amerindian-themed play, A Fair Maid’s Tale, was published by the Majority Press in the collection Caribbean Mythology and The Modern Life (2004).

That play, like others in the collection, has a number of distinguishing features. It treats with mythology, but also questions tradition and places everything in the context of modern life in the Caribbean. Such plays can move among popular culture, appeal to the youth, and relate to contemporary living, using folklore to teach relevant, vital principles of existence. These qualities are particularly exhibited in Anancy’s Way and A Fair Maid’s Tale.

The latter is a one-act play that explores a number of planes in the traditional life of the Amerindian peoples. What makes it different from plays such as Inkle and Yarico and those of the ilk of San Gloria is the serious treatment it affords its subjects. It avoids any sensationalism, using its Amerindian content to make major statements. It is set in a Guyanese interior village in the midst of the rainforest and an ancient traditional life in which a number of beliefs and practices can be dramatised.

At the centre of the play is a version of the Bush Dai Dai, who is a benevolent spirit, unlike other versions elsewhere, who protects in the forest. A main beneficiary of this protection is the heroine Green Fern, a teenager who is a different, adventurous, and courageous individual, unlike the conservative girls who are her friends and peers. The villain of the piece is the sinister figure of the kanaima, a resident of the village secretly trained as a highly skilled assassin. While terribly afraid of him, the villagers do not know his identity, but Green Fern’s grandfather, the village Piaiman, knows of his presence. These are some of the deep spiritual beliefs that inform the plot and take the audience into the Amerindian community.

Yet in the middle of all that lore and traditional spiritualism, Mohamed manages to make statements about society and human concerns. The village suffers a food shortage and the unconventional, adventurous Green Fern sneaks away with the piaiman’s staff, which she takes to the river. She manages to use its power to achieve what her brother and none of the men could, reaping a huge harvest of fish from the river. She excitedly shows her brother the harvest and sets out to surprise and feed her people. But her brother, feeling envious and emasculated, seizes the fish, pushes his sister into the river, and takes the catch home to feed the village, claiming the glory as his.

The play’s feminist concerns expose the highly patriarchal nature of traditional society, which is challenged by Green Fern but accepted by all else. The very title is ironic. After being pushed in the river to drown, Green Fern is rescued by Makonaima and transformed into a ‘fairmaid’, a folklore figure of the waterways who plays a protective and corrective role. But according to the title, she is also a fair maid – referencing her beauty, honesty, and good intentions – who proves that women can achieve and lead.

The play Anancy’s Way similarly uses myth in the figure of Anansi, the trickster with the superior brain power, to teach lessons to youths in school. That becomes important to both that play and the story of Green Fern because the collection of plays was written to be performed by schools. Such plays are rare in Guyana partly because of an absence of suitable published material and they are in great demand among secondary schools. Through this drama, the students can also learn about the indigenous culture and heritage.

One needs to search to find the drama that treats this heritage. Another place that can reward such a search is the National School of Theatre Arts and Drama (NSTAD). Among the coursework, there is the creation of short plays using avant-garde techniques such as the ritualistic play. A number of these creations delve into Amerindian mythology and legend, such as Skilpaata (turtle), The Legend of Kako and myths of origin such as how the monkey came into being, and how water came to flow through the village in the form of a stream.

In this way the NSTAD has added to the collection of drama that treats, explores, and reflects the environment of the Amerindian culture in Guyana. What these plays show, such as some of those in NSTAD, the work by Michael Gilkes, Subraj Singh and by Paloma Mohamed is that the explorations are not limited to interior traditional life, but dramatise deep elements of it in order to analyse, discuss and teach about many things in the wider social context of the modern world.