Dear Editor,

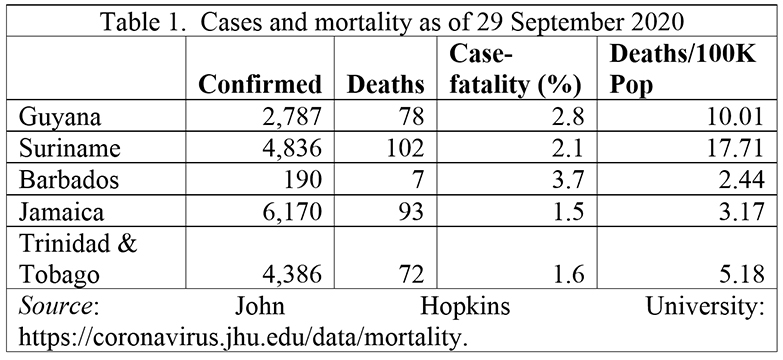

On 27 September, Stabroek News informed the Guyanese public that the government had commenced “the distribution of the promised $25,000 cash grant for COVID-19 relief.” This is an interesting initiative at a critical time, a time of a pandemic that is becoming more alarming in Guyana on a daily basis. As 29 September, Guyana’s case fatality rate (deaths as percentage of confirmed cases) was 2.8 percent compared to 2.1 percent for Suriname, 3.7 percent for Barbados, 1.5 percent for Jamaica and 1.6 percent for Trinidad (see Table 1). That is, only the more densely populated Barbados has a higher case fatality rate than Guyana. This is probably not unusual but still troubling given the poor and disorganized state of Guyana’s health care system and its incapacity to generate useful data. For example, the Ministry of Health has not produced COVID-19 deaths by ethnicity, gender and age group within a given region and one must remain suspicious of the quality of other COVID-19 data it releases (see the letter by Dr. Somdat Mahabir, SN, 27 September).

While timely, the relief is a pittance: $25,000 cannot feed the typical household in Guyana for even one month. I do not know how many households there are in the country today, but there were 210,124 households in 2012, according to the census of that year. That figure was 27,515, or 15.1 percent, more than the number of households in 2002. On the other hand, the average number of persons in a typical household declined from 4.11 in 2002 to 3.46 in 2012. In fact, mean household size has been falling since at least 1980, when it was 5.07 but it is unlikely to be less than 3.0 today. It is reasonable to expect the continuation of this trend, which would suggest that the number of households today would exceed 210,124.

Because of the unavailability of the requisite data, assume, unreasonably, that the number of households in 2020 is the same as that of 2012. Then the COVID-19 relief programme will cost G$5.3 billion, which is about US$25.1 million. In my view, this is a chicken feed relief programme, which seems more like a political show than a humanitarian endeavour. The dire health predicament has apparently created the opportunity for cheap political points, which the government has grabbed. The government could have upped the cash grant to at least $70,000, which is the minimum monthly wage of a public servant. Unlike the current timid COVID-19 relief programme, the larger one would have been a bold effort to provide increased relief at a time when poverty and inequality are both on the upswing. It would have also enhanced the public perception of the Government’s commitment to the people of Guyana. Unfortunately, the PPP seems unable to distinguish tokenism from real, substantive efforts directed at making peoples’ lives less miserable.

Aside from its size, the relief programme raises other issues. First, the logistics and administrative hurdles of the “meet-fill-form-and-distribute” method is only one-half of relief equation. The other half is darkness: what are the monitoring and accountability mechanism of the programme? How does the Government know that funds have been distributed to each household and that a portion has not been siphoned off? What is the administrative cost of the programme, in absolute amounts and as a percentage of the amounts distributed?

Second, how long will it take to ensure that each of the at least 210,000 households gets its $25,000? Months? What is the size of the team that is doing the distribution? Does the recipient get cash or a cheque? If cash, then the distribution teams must be ferrying around millions of dollars, which raises the issue of security but also of corruption, which leads to the next “dark” issue.

Third, given the persistence and pervasiveness of

corruption in Guyana, how does the government ensure that funds intended for Guyanese are not diverted into the pockets of unethical public officials? According to the same article in Stabroek News, Vice President Bharrat Jagdeo offers an answer: “He added that an extensive form has been developed that has the name of the recipient and their identification information and the monies will be given in the form of vouchers with security features that will make them hard to duplicate. He explained that where there might be more than one family living in one home, representation will have to be made outside of the normal distribution.” The last clause of the last sentence, “… representation will have to be made outside of the normal distribution,” is troubling. It seems to offer yet another route to corruption, to illegal and unethical sucking activities of public officials that could drain a portion of the pittance relief from poor people and into the pockets of public officials. The fact of the matter is that the government does not have a relatively safe way of distributing the $25,000 cash grant.

Fourth, the relief programme could offer insights and lessons that would be useful to any future effort to share the coming oil wealth (oil prices will not remain low indefinitely). To ensure that the COVID-19 relief effort does not go waste, the entire process must be documented and an evaluation must be done after the exercise is completed. The evaluation report must be made public and the government must have some way of listening to the voices of the people.

Fifth, and building on the fourth, it is time that the government develops an electronic method to distribute relief to Guyanese (households or citizens). Most adult Guyanese now have a bank account. There were 505,677 deposits accounts at commercial banks in 2018, up from 406,468 in 2005. Assuming one account per person, them there were more than one deposit account at commercial banks for Guyanese 20 years and over; that figure would drop to 97 percent if the age is lowered to 15 years. These figures are no more than indicative as upper-class people have several accounts per person, while access to banks and ATMs are far better on the coastal than hinterland regions. But the point is this: apparently most Guyanese adults have bank accounts, which is a prerequisite for an electronic transfer system. Such a transfer system is faster, incomparably less costly, less time consuming and less prone to corruption. Systems to electronically transfer funds to citizens exist in many countries, rich and poor, including the US and India and Sri Lanka.

In sum, the COVID-19 relief programme is a welcome and timely initiative. But I fear it is too small, costly, time-consuming, open to corruption, poorly conceived, planned and executed, and with no follow-up effort to gauge its effectiveness.

Yours faithfully,

Ramesh Gampat