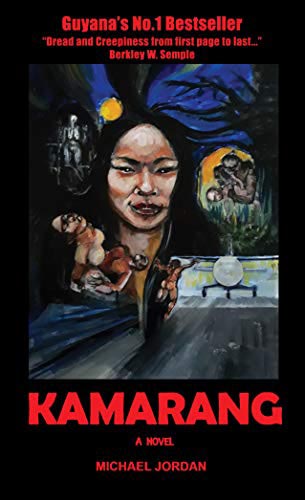

(Michael Jordan, Kamarang, Georgetown, published by Michael Jordan, 2017; with illustrations by Harold Bascom; 500pp.)

(Michael Jordan, Kamarang, Georgetown, published by Michael Jordan, 2017; with illustrations by Harold Bascom; 500pp.)

The name Kamarang carries with it a significant resonance for Guyanese. It is the name of a place in the interior of the country associated with mining, porkknockers and an indigenous heritage. Ron Savory’s painting Kamarang, evokes it all in one excellent piece of art – the rainforest, the prospector’s camp, the seaminess, the lore and the supernatural.

In contrast to the brevity of Savory’s small canvas, the name with all its invocations commanded attention with the publication of a much more voluminous work, a novel with the same title, written by Michael Jordan, with illustrations by Harold A Bascom and published in 2017.

As a novel, it is extremely intriguing and suspenseful and fits comfortably into a number of different genres. It is at first glance a popular novel, but it goes much deeper and is fortified by attributes that transcend works that are typical of that form. Apart from being Amerindian literature, it is detective fiction, a mystery novel whose protagonists investigate its elusive mysteries clue by clue. But it also has the popular characteristics of a horror tale, while its literary strengths also classify it as belonging to a not very common type of Guyanese novel – fiction of the supernatural.

The novel’s hero, Michael Jones, an educated, under-employed youth, is drawn to pay a visit to a brothel one fateful night, which deepens his experience, but shocks, and changes his life and outlook thereafter. He is casually introduced as physically fit, but it turns out that his robust physical condition is very significant to the plot. His visit to the red light district around Lombard Street in a seamy quarter of Georgetown gets Jones entangled with an exotic, mysterious Amerindian beauty named Lucille. She proves to be the gateway to a world he never expected or imagined. The novel propels its readers through the Guyana interior, realms of the porkknockers and prostitutes in an environment of sex, and the worst nightmares of what is known colloquially as ‘the bush’.

As an experienced “bushman” named Vibert Sealy takes over the skillfully managed narrative, the adventure plunges into the nightmarish encounters with the dreaded bush dai dai, the visitations of a succubus whose haunting presence accompanies the protagonists as they return to Georgetown. Jones becomes a victim of this experience, both demonstrated in the tale and symbolised by his physical decline and dangerously deteriorating health. All are dragged into a whirlpool of ancient myth, a revenge ritual, tragedy, and death. Through his grandmother, a spiritualist, Jones discovers his distant Amerindian ancestry which explains his link to an ancient curse being pursued up to the present time in a web of vengeance, blood, the supernatural and spirituality.

Michael Jordan, is a journalist by profession, and it is interesting to peruse Kamarang as fiction through such lens. A few such Guyanese novels exist. Tomorrow Is Another Day (1994) by Narmala Shewcharan is among the more prominent and accomplished, distinguished by its fictionalising of the notorious political regime of the PNC in the 1970s and 1980s in Guyana. Another is Godfrey Wray’s Beyond Revenge, which is a less proficient, fantastic tale out of the Guyana Defence Force that is not easy to take seriously.

Jordan’s novel is adroit and may be regarded as more; not just fiction by a journalist, but as a kind of journalistic fiction. If there are relevant connections at all with his profession, they are factors towards the quality of the craft of fiction. It well surpasses journalese, drawing instead, on the most fortifying journalistic elements. For instance, it is very strong on research, both primary and secondary. Documentation is careful and capable as it benefitted from such colonial documentalists as the Rev William H Brett and Walter Roth, as well as the archives of the Guyana Chronicle newspaper. It is also informed by field work in the Georgetown red light districts as well as in Amerindian communities, particularly among the Akawaio, and in mining camps at Kamarang itself. These have lent the novel meticulous detail of fact and description.

These elements of the journalistic are cleverly employed by Jordan as form and genre. They create the kind of fiction that sets out to convince its reader that it is history – a journalist’s record of factual events. There are news reports, records of dates, actual clippings from newspapers with real names of people now deceased, such as reporter Albert Alstrom and famous pathologist Dr Leslie Mootoo. Many scenes are set in the well-known Ritz Hotel in Lombard Street, which was, in fact, destroyed by fire, and Jordan builds that burning in as part of his plot.

There are even suspicions of autobiography. The hero is named Michael, which is more than coincidence and makes use of personal experience among the strategies. On the whole, the tale is a very informed but a very dispassionate narrative.

Yet, Kamarang’s most enduring feature is its treatment of oral literature. It exhibits a valuable demonstration of Amerindian folklore, including a range of mythology. The author sets out to preserve this powerful reserve of knowledge and indigenous patrimony now under threat of becoming moribund. He contends that the art and practice of storytelling are effective ways of helping to achieve this, and the popularity of his novel will contribute in this regard. The possibilities of exploiting this great store of wealth are many and treatment in published literature is one of these. This novel can invite and generate interest and keep folklore alive.

There is a very small corpus of literature of this nature, including another popular novel The Return of the Half-Caste by Lewiz Alyan. Alyan’s tale stretches credibility, but hardly anything else exhibits more of the hidden, spiritual beliefs of the deep interior. It is a work of the Amerindian occult, the supernatural and the magic with myth and lore. A dark, gothic novel, it is sensational in its treatment of sexuality and its commanding knowledge of diving and mining for diamonds.

Kamarang includes a bit of social realism as it intertwines the ‘bush’ experience with the dim corners of the red light quarters among hotels frequented by visitors from the interior and prostitutes. It recreates a quality of this life in an older Georgetown once popular around the Lombard Street area. As if to assist in the creation of that atmosphere, the writing is sensual and sensuous with a perpetual appeal to the senses even in the vivid capturing of the interior locations. It is intoxicatingly uninhibited as it crosses the threshold of both geographical and social boundaries as if they were one.

Yet what stands out more than the surprising avoidance of sensationalism is the informed research as well as the detailed and equally vivid environment of the dai dai. Unlike the benevolent version of the bush dai dai used in other works, this mythical tribe with feet turned backwards has a propensity to violence and cannibalism. They appear at the centre of the mystery and the horror in the plot of this novel, described by Akawaio informants like the piaiman Perez.

The works of Roth and William Brett document a range of this material from which Jordan has drawn. In the novel, Jones finds a poem amid a revealing expose of an ancient curse – background to the mystery he is at pains to unravel and about which his grandmother advises him. Jordan makes use of a poem found in Brett. It is an intriguing legend from the archives of ancient Amerindian mythology. This novel retains popular elements enriched by the other reinforcements that lend it some weight.

Several excerpts of the novel were serialised in the Kaieteur News, which Jordan has been affiliated with for some time. This is a strategy employed in the popularisation of novels through history. Some of the classics were first published chapter by chapter, serialised in magazines. The great Charles Dickens was known for this. Similarly, West Indian novels that helped to establish social realism in literature went through that process. H G de Lisser, who was editor of The Gleaner newspaper in Jamaica, started publishing his novels in serials in the newspaper around 1913, before they appeared in the regular printing of novels.

Jordan’s Kamarang is a thriller; entertaining and easy to read. It appeals to readers looking for a suspenseful, gripping story. But it is at the same time deep with powerful themes thoroughly informed by Guyanese Amerindian mythology and oral literature. All told, it is a flamboyant work of the imagination.