There were two very important items of interest to literature in the news over the last fortnight. On October 8, the Swedish Academy in Stockholm announced that the 2020 Nobel Prize for Literature was won by one of America’s foremost contemporary poets, Louise Gluck, “for her unmistakable poetic voice that with austere beauty makes individual existence universal.”

There were two very important items of interest to literature in the news over the last fortnight. On October 8, the Swedish Academy in Stockholm announced that the 2020 Nobel Prize for Literature was won by one of America’s foremost contemporary poets, Louise Gluck, “for her unmistakable poetic voice that with austere beauty makes individual existence universal.”

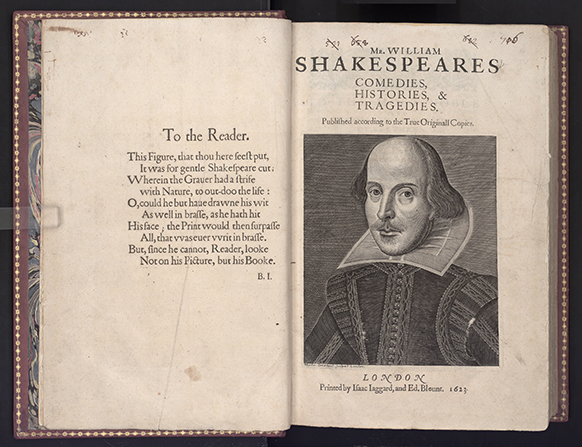

Then on October 14, the famous auction house, Christie’s, announced: “A rare 1623 book that brought together William Shakespeare’s plays for the first time sold for a record $9.97 million at auction on Wednesday” in New York. The selling price was a new world auction record for any printed work of literature, according to Christie’s.

While the Nobel winner is claiming the most prestigious literary award normally presented to the most outstanding works of literature for the year as selected by the Swedish Academy, the distinction achieved at Christie’s is of a different order. Both celebrate in different ways, the best of literature. The Nobel highlights the creative work of the moment, the triumph of 2020. What happened at the auction suggests recognition of the most valuable literature of all time – creative work that has triumphed over the passage of centuries.

Record prices at auctions tend to say something about how collectors and the world value the works and the artists, and the highest prices tend to be consistent with the canon of the best painters and writers throughout history. In fine arts, Italian painter Leonardo Da Vinci’s “Salvator Mundi” holds the world record for the highest auction price. (Paintings fetch much higher bids than books, and the highest prices tend, for the most part, to be consistent with critical notions of the canon). The Old Masters dominate, suggesting, as with the literature, works that triumph over time.

Shakespeare had made this extraordinary and prophetic claim about his own art:

“So long as men can breathe or eyes can see,

So long lives this and this gives life to thee.”

The auction at Christie’s bears this out, since it attests to the longevity, the immortality of his work. But there are more important reasons why this 1623 book is important, and the meaning of its value to modern readers, students, or collectors. This rare document was bought at the auction by a private American collector Stephan Loewentheil, owner of a rare books shop. Loewentheil significantly said: “It is an honour to purchase one of only a handful of complete copies of this epochal volume. It will ultimately serve as a centrepiece of a great collection of intellectual achievements of man.”

The book is titled Comedies, Histories and Tragedies, a collection of 36 plays by Shakespeare compiled by two actors John Heminge and Henry Condell, who were the playwright’s friends, and published in 1623. It is much better known as the First Folio of 1623 and is an extremely valuable document. It includes 18 plays not previously published and might have been lost otherwise. But apart from that the value of the First Folio lies in the fact that it is the most reliable, correct, and trusted edition of the Bard of Avon’s collected plays and is the first complete collection.

A publication titled William Shakespeare: The Complete Works, edited by Charles Jasper Sisson (1954), includes a 37th play, Sir Thomas More, which was only published in 1644. However, Sisson explains that this drama is acknowledged to be not entirely Shakespeare’s work, but was written by “diverse hands”. It was the collaborative effort of five writers, one of whom was the very popular playwright Thomas Dekker, along with Shakespeare whose handwriting is clearly recognised in parts of the manuscript. All of this requires explanation.

Much of the great value of the First Folio arises from the prevailing situation regarding drama, printing, and publishing in the Elizabethan period, the sixteenth and the seventeenth centuries during which Shakespeare worked. The very title in full of the volume can reveal some of these prevailing conditions. It is Mr William Shakespeares Comedies, Histories, & Tragedies, Published according to the true originall copies, London, printed by Isaac Laggard and Ed Blount, 1623.

This First Folio is accepted as an authentic edition and a full collection of the plays, as this title attests, and after its first publication it was reprinted several times over a very long period. There were many other publications of the plays, most of them by Shakespeare himself, but many of these contained errors or were not approved, legal copies. Other publications which are acknowledged as based on Shakespeare’s original manuscripts include the quarto editions of 1598 and 1600. There were five other quartos published at different times, which demonstrates the popularity of the plays, which were quite in demand, but are not all trusted copies.

The difference between folio and quarto has to do with printing conventions where a sheet of printing paper was folded before printing – the folio was arrived at by folding the sheet once and was the largest leaf size in printing. For the quarto, the sheet was folded twice. But the difference was also informative to editors since most of the bad, pirated editions and publications were quartos.

All of this came about because in Shakespeare’s time there were no copyright laws and writers had little protection. Plagiarism was fairly common and pirated copies of a playwright’s work were prevalent. Anyone who first printed a play could claim it as theirs. Sometimes actors who performed in a play would later steal the work, using their scripts and memory of the lines to go to a printer and have the play published. One safeguard against this was for the writer to be the first to take his manuscript to a publisher, but even that did not work because pirated copies still appeared.

The best protection was the Stationer’s Register. A playwright could go and register his manuscript so that it was legally documented in his name. Shakespeare was a bit careful in this regard because he made frequent use of the Stationer’s Register, in addition to publishing his plays himself. Editors and researchers have been much assisted by checking the Register for the records and dates of plays.

Another relevant issue was the method of printing. Plays were printed from the handwritten manuscripts of playwrights and often there were ideographic problems. The typesetters had to decipher bad handwriting. To make things worse Elizabethan English was not completely standardised so that not only grammar and syntax but spelling of words and the way letters of the alphabet were written contained variations. These were enough to introduce errors in a printed text.

That is why editing is a large and important part of Shakespeare scholarship. Editors and researchers often find themselves having to choose between two variations of the same sentence or words in a text and decide which is the correct one. They have to try to decipher the correct meanings out of the use of a word or sentence when two different versions of the same text appear before them.

For example, in Hamlet, the Prince of Denmark strongly disapproves of the state of affairs in the country. He disapproves of his uncle the king, is disappointed in his mother, he feels tainted and is depressed. He wishes that he could just fade away and die but cannot kill himself because suicide is forbidden by God. There are two variations of his speech. In one version he says, “O that this too too solid flesh would melt /Thaw and resolve itself into a dew /Or that the Everlasting had not fixed /His canon ‘gainst self slaughter”.

In the other he says, “O that this too too sullied flesh would melt, . . .”. One of them is an error, either “solid” or “sullied”. Was Hamlet saying his flesh was too solid and robust and could not just melt away? Or was he saying his flesh was tainted by the sordid situation and he wished it would melt away?

This error is one of the many that resulted from the conditions described above in the handwriting and the printing. One therefore would have to try to determine what Shakespeare meant to say. It has to be interpreted. On the other hand, one can depend on the more reliable text. The version that appears in the good folio is likely to be correct as against what appears in a pirated version. In several of these cases editors relied on the Folio and on a text that was printed from Shakespeare’s original manuscript.

Therein lies one of the values of the First Folio as an authentic document. Besides, Shakespeare first went into the theatre as an actor. He learnt his drama from actually working on the ground. Also, he directed his plays and had firsthand knowledge of the stage. His manuscripts would have stage directions and notes to his actors written into the text. Editors relied on those to determine whether a text was reliable or authentic.

That is the case with the First Folio of 1623. There is no claim that it was error free because there were cases where plays in that collection had problems. So the First Folio fetched its record price because it is a rare document, but also because it sets out and acknowledges Shakespeare’s different types – “comedies, histories, and tragedies”, and can claim not to be pirated scripts, but was “Published according to the true originall copies”.