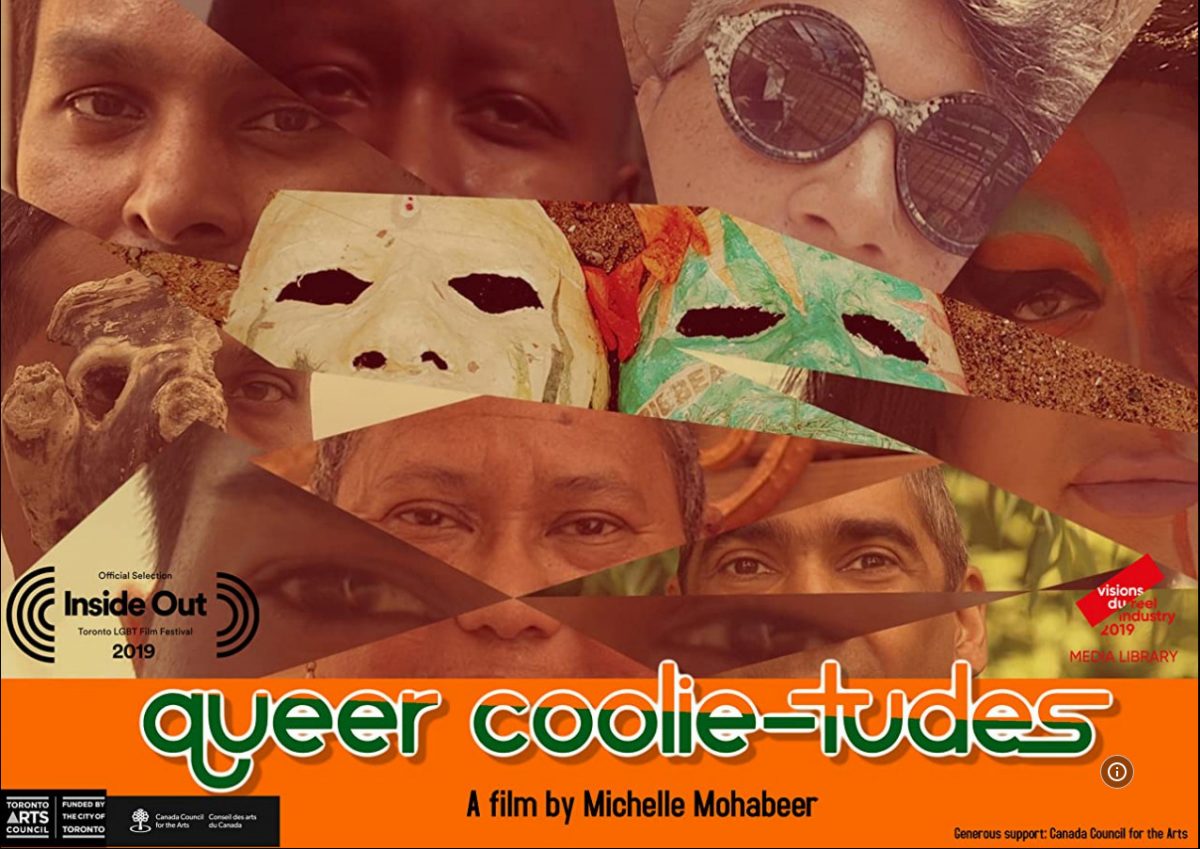

The Society Against Sexual Orientation Discrimination’s Spectrum Film Festival, which celebrates films by and about queer identities, is running virtually for the month of October. One of the features of this year’s festival is “Queer Coolie-tudes,” a work by Guyanese-Canadian documentarian Michelle Mohabeer, who offers a distinct perspective on queer identity that seeks to explore the intersections of race, sex and gender.

The Society Against Sexual Orientation Discrimination’s Spectrum Film Festival, which celebrates films by and about queer identities, is running virtually for the month of October. One of the features of this year’s festival is “Queer Coolie-tudes,” a work by Guyanese-Canadian documentarian Michelle Mohabeer, who offers a distinct perspective on queer identity that seeks to explore the intersections of race, sex and gender.

Mohabeer, a queer filmmaker, describes the film as ‘a creative essay documentary and queer ethnography which traces the intergenerational lives, histories, identities, familial relations and sexualities of a diverse range of subjects from the Indo-Caribbean diaspora in Canada.’ That descriptor speaks to the ways that “Queer Coolie-tudes” exists on the boundaries of numerous intersections. Mohabeer’s work is most explicit as a document of queer confessionals as it features persons of the community speaking directly to the development of their queer identity. The film, though, is just as intentional about speaking to the issues of race and racism in (and out) of the queer community. Moreover, by centring the film on Canadians of Caribbean heritage, Mohabeer’s work becomes a diasporic document explicating the frissons of displacement that come with distinguishing one’s cultural identity between competing locales.

“Queer Coolie-tudes” is structured in eight sections, each featuring an extended interview with a queer person delivering their life’s tale. Mohabeer begins with her own story, narrating her growing awareness of her own queerness. Her perspective sets the tone for the other sequences, which each recount burgeoning queer desire amidst a culture of living as a member of a minority group in the western worlds. As the sequences develop, it lends a note of repetitiveness to the stories as the sequences seem to bleed into each other. But as the film continues, the occasionally rote nature of the presentations becomes illuminating in some ways as we see the ways the stories converge and then diverge. The intersections – family strife, shared racism, recognition from an early age – are as fruitful as the divergences. And the film becomes richer for those divergences.

Trinidadian drag-performer Tifa Wine articulates the rupture in their drag persona, which rather than presenting the verisimilitude of womanhood in her persona, deliberately subverts the notion of realism in her drag. It speaks to a compelling take on gender identity that feels thoughtful in its examinations of performance and gender.

Another poignant section, on Lezlie, who is a callaloo mixed Trinidadian living with a disability – becomes the richest sequence for the ways it builds on and then extends notions of queerness on screen. Lezlie’s story is a rich perspective on aging in the queer community, disability studies and the ambivalence of performing one’s mixed heritage in a culture that exists in the monolith. She’s a personable narrator and injects her sequence with a propulsive momentum that feels compelling.

There are moments where a clearer through-line from start to end feels more necessary for “Queer Coolie-tudes”. The discrete ways the stories are presented tends to make the film seem more episodic than holistic as Mohabeer tries to grapple with both the singularity of each subject and the sharedness of the queer identity. Andil, one of the subjects, speaks potently on the resistance of performing an essentialist perspective of his sexuality and his race in his artwork, which feels like a profound thought the film could push further. Intriguing, albeit not explored, are the ways the film’s focus on migrants implicitly suggests a class distinction between queerness for these Caribbean nationals abroad and contemporary extensions of queerness in the Caribbean currently. There’s an unexplored frisson in that interaction that briefly reveals itself when some of the subjects, some not born in the Caribbean, speak of race and gender situations in the region. Moments like this seem to emphasise the chasm between experiences at home and abroad and distinguish the sometimes-battling perspective of what it means to be queer in the Caribbean without the luxury of migration. Mohabeer could well explore a messier engagement with this dichotomy in later works.

At times, “Queer Coolie-tudes” feels trapped by its confessional format, giving way to a documentary aesthetic that comprises ‘talking heads’ more than anything dynamic with the form. Mohabeer attempts to inject some dynamism in moments, peppering the talking with occasional images that sometimes meet jarringly, sometimes more seamlessly, with the words. But, if “Queer Coolie-tudes” is less impactful aesthetically, it speaks to the film’s jagged, but essential, cross between feature filmmaking and film as activism. As an anthropological document, Mohabeer’s work is assured and distinct and even more vital and specific as a work of diasporic Caribbean cinema. In its current format, the work seems like it should be a beginning of a series of similar kinds of confessional works that seeks to have queer identities speak their truth – expressly and emphatically – to the camera. And it’s on this level, that “Queer Coolie-tudes” retains its resonance.

SASOD’s Spectrum Film Festival continues each Saturday in October.