In the ceremony of White

The cyclamen girl would answer

To her name

Aphrodite!

Gives rote answers

About promises

Of the godfathers

Ave Maria!

Remembering

First the drums

Then the women

Called out her name

Atabey!

Her other name

Oshun!

As she whirls

Into the circle of grief

For her fleeting childhood

Passed like the blood

Of her first menses

Quick and painful

Name her

Rhythm!

Song!

Drum!

Mahogany-tipped breast catches

The glare of the fires

Women of the moon feast and fast

And feast again

Name her

Aphrodite! Mary! Atabey!

Orehu! Yemoja!

Oshun!

For her newly arrived wound

Name her!

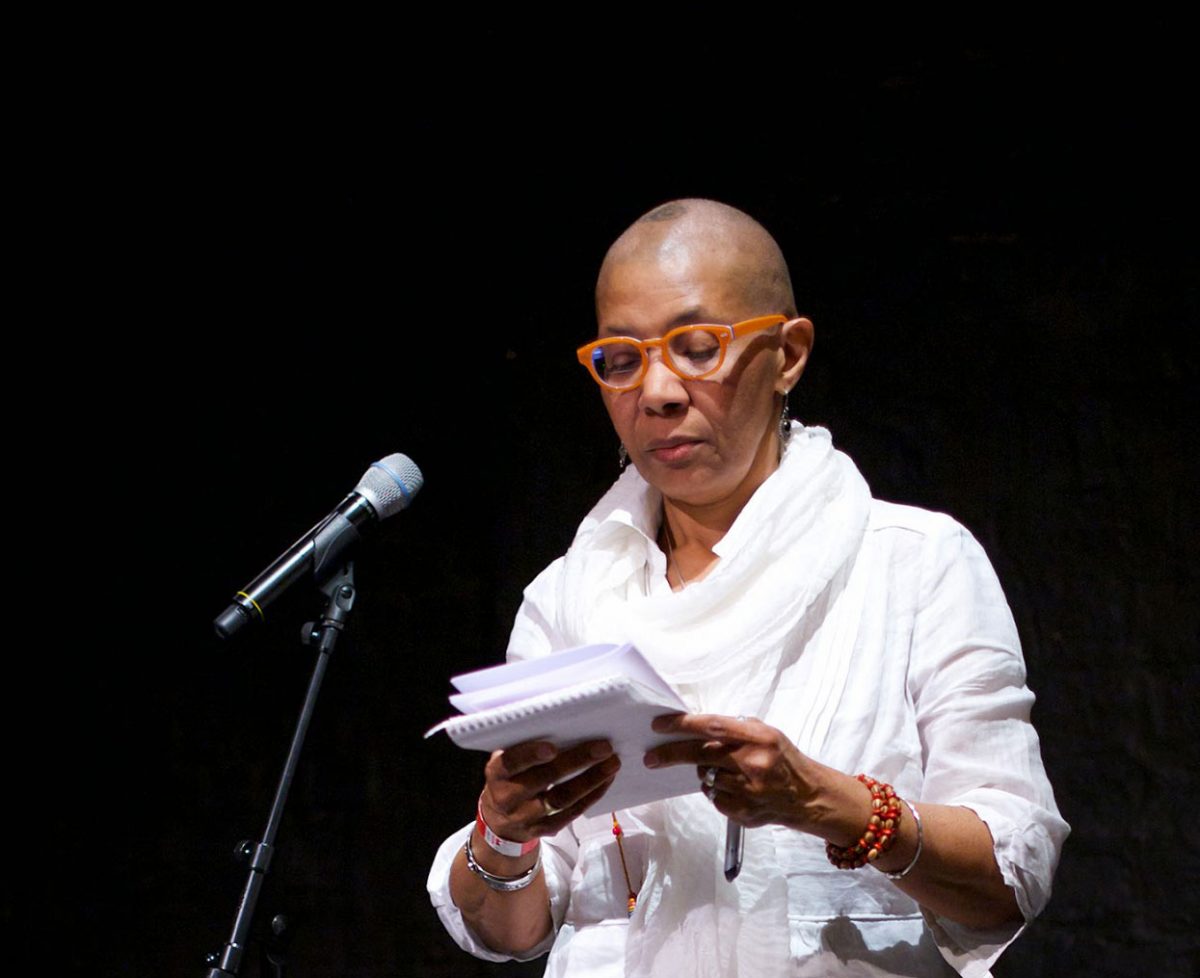

– M NourbeSe Philip

A transfiguration can be many things. The word itself suggests a certain shape-shifting quality with infinite artistic possibilities when exposed to the imagination, and especially the poetic imagination. But basically it means change of form or appearance.

It has, however, been appropriated by Christianity and has become known and commonly associated with that religion, as a term belonging to the faith and refers to the Transfiguration of Christ. The story narrated in the Bible, Matthew 17: 1-9, tells about the elevation of Jesus before his ascension into heaven after the resurrection.

This poem exploits the religious reference, but transcends the Christian and engages other faiths, and traditions. It also plays on extended meanings of the word to involve transformation and even the concept of the transmigration of the soul. But basically it is a poem about a rite of passage, which is a formal ritual or observation of tradition in different societies to mark a human change – the passing of a person from one state or stage of life into another. The poem is most likely dramatising a ritual of puberty for a young girl; or it is a naming ceremony. But it is done in modernist poetic form.

The artist is Canadian poet, novelist, and essayist Merlene Nourbese Philip, who identifies herself as M NourbeSe Philip. She was born in Tobago and studied at the UWI before leaving Trinidad for Canada in 1968. She is an Attorney-at-Law but gave up the practice to be a full-time writer. She is quite celebrated and decorated, especially for the novel Harriet’s Daughter (1983) and the collection of poetry She Tries Her Tongue, Her Silence Softly Breaks (1989), which won the Casa de las Americas Award.

Philip is an activist against racism and is known for taking on social issues in her work. She is also praised for her innovative and radical use of language and form, especially for such constructs and exhortations as:

. . . and English is

my mother tongue

is

my father tongue

is a foreign lan lan lang

language

l/anguish

anguish…

But this innovative form was characteristic of Kamau Brathwaite decades ago. What Philip has made great strides in and has truly made hers are her bold excursions into linguistic and formal post-modernism as in the title poem of her famous collection, “She Tries Her Tongue, Her Silence Softly Breaks”. It is the kind of linguistic and dramatic distinction found in “Transfiguration”. This poem, in a way, dramatises the quotation from Ovid’s The Metamorphoses that Philip uses in the title poem: “All things are alter’d, nothing is destroyed”.

The theme and concept of transformation and that of transmigration run through “Transfiguration” cleverly and unobtrusively. It is a rite of passage in which the traditional and indigenous blend expertly with the European religion and mythology. It is a “ceremony of White” – significant in the traditional, spiritual colour coding, and the girl at the centre of it is “cyclamen” – presented as a plant with early blooming flowers. It is, therefore, a ritual of puberty, and the Greek goddess Aphrodite, associated with love, beauty, and fertility is invoked.

In a kind of antithesis, the girl also becomes the incorporation of the Christian Holy Mary in the reference to “Ave Maria”, and almost in the same breath, to African deities. Oshun is a Yoruba goddess, the opposite of “Maria”, but not far removed from Aphrodite. But as far as spiritual ritual is concerned, she is also associated with water and purity, and is a river Orisha. She is very prominent in Orisha worship and in the Shango religion in Trinidad and the Eastern Caribbean. There is further reference to Yemoja, who is also a Yoruba goddess of water – of rivers. In other sources she is called Yemanja.

Clearly, Philip is drawing on her Trinidad and Tobago background, since these traditional spiritual references are all found in the Orisha and Shango tradition in that country.

The poem also takes us through “rhythm, song, drum”, all important to the celebration, the possession experiences of that religion and its ceremonies.

Yet, this is all being compared to the Transfiguration. The poem is of the sublime experience. The transformation from one state of life to another is an elevation for the girl at the centre of it. Additionally, the poem is a naming ceremony. This also draws on the traditional spiritual because a name gives identity. Here, a name is not just a word, but a form of existence. In some societies a name is even an acknowledgement that the subject is human or has been inducted into the family of humans. The implications of this poem “Transfiguration” are wide, infinite and inspiring.