By Nikita Blair

“My mother is a star, one of many bright jewels who sing praises in

the skies, who view us from on high…She watches me now from her old

throne, one more twinkle in the constellation Pushya, a figure as distant as the characters in the bedtime stories she once loved to tell me. In the evening, I see her clearly, laughing with her companions, radiant.” (p.4)

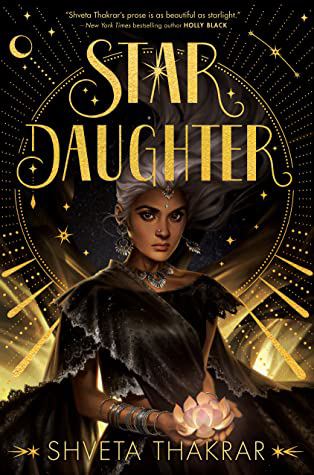

There are times when I get superficial with my selections for reading. I’ll be scrolling through Book Twitter or Goodreads, and I’ll see a book cover so beautiful that I, literally star-struck, don’t even try to find out what the book is about or who the author is. I just grab it or save it to my To Be Read (TBR) list just because I want to know what’s going on with that cover.

Star Daughter, Shveta Thakrar’s debut Young Adult Fantasy novel, was one of those books. Needless to say, I have no regrets. It was one of those books that I sat down and read to the end in a single day, which says a lot given that the book is 448 pages long.

Star Daughter, Shveta Thakrar’s debut Young Adult Fantasy novel, was one of those books. Needless to say, I have no regrets. It was one of those books that I sat down and read to the end in a single day, which says a lot given that the book is 448 pages long.

As Diwali fast approaches, I thought this would be an excellent novel to review for our Hindu brothers and sisters, who will be celebrating while social distancing in a few weeks.

Star Daughter is about a teenager named Sheetal Minstry, whose mother is a star and whose father is a Nobel Prize-winning astrophysicist. When Sheetal was a young girl, her mother left her and her father behind in Edison, New Jersey, to return to her home in the Pushya nakshatra, one of the lunar mansions that Sheetal sees as a constellation when she looks at the night sky. Before leaving, her mother tells her that no one should know that she is a half-star and both Sheetal’s father and her eccentric auntie, Radhika, insist that she dye her silvery hair black and do her best to avoid drawing attention to herself.

Several days before her 17th birthday, strange things begin to happen to Sheetal. Her hair rejects the black dye, the cosmic song bound inside her threatens to burst forth at the most inopportune moments, and there’s a dangerous and unexplained heat rising in her that she can’t quite explain. On top of this, in a moment of typical teenage rebelliousness, Sheetal sneaks off the meet her boyfriend, Dev, and accidentally discovers that his family harbours a dark secret that threatens her existence as a star.

This strange revelation triggers a series of events that lands her father in the hospital and forces her Auntie Radhika to finally set her on the path to uncovering her nebulous history and return to the stars. There, she finds that the heavens are no paradise, as a political scandal unfolds around her that threatens both sides of her family, her friends and the wider world.

“What did she want? Adventures. Cupcakes and kulfi. To be star bright and mortal dark and make her own choices, too. To not be bound by other people’s expectations. More than anything, to be seen.” (p. 50)

Before I go on, I must admit that I only have a superficial knowledge of Hinduism. Nevertheless, I was intrigued by this story, and particularly the way Thakrar turned Hindu cosmology into family history for Sheetal while not making it stuffy. Throughout the story, we can empathize with Sheetal. She’s just an awkward teenager who just wants to be her most authentic self: she wants to sing, wear her hair in its natural state, have a boyfriend and enjoy what little of her summer vacation she can before her Auntie forces her to attend college prep classes. Her humanity, with its immediate priorities, worries and blunders, is absolutely relatable.

This, in turn, helps us to empathize with Sheetal’s foils. Her father and Auntie want her to hide her cosmic heritage for some mysterious reason. They go so far as to encourage her to be an unwilling introvert and to stay away from boys, which directly conflicts with Sheetal’s extroverted nature and her relationship with her boyfriend, Dev. On the flip side, her best friend, Minal, says well-meaning but inane things like “If I were you, I would just let my hair out”, without actually knowing how painful that simple, flippant statement is to Sheetal. Two energies are tugging at Sheetal, leading to a confusing and messy situation that’s quite reminiscent of teenage years.

“You don’t get it, Sheetal thought. Magic isolates you. You’re this

misfit who doesn’t belong anywhere, and you want to make it all

go away, but at the same time, you crave it, and you can’t help

craving it. You’re just stuck.” (p. 36)

When Sheetal finally reconnects with her cosmic family, they also pressure her into being someone she’s not and doing things that go against her personal agenda. She just wants to heal her father, but her cosmic relatives want to use her as a part of a complicated political plot that will affect both heaven and earth. Again, we empathize with her because our families can get us all tangled into things, we’d rather avoid but can’t for some reason or another.

Thakrar’s writing made it easy to immerse myself in Sheetal’s frantic navigation through her families’ respective pursuits and her own. The best part is that the novel does more than just portray the awkwardness of teenaged life though common YA tropes. It uses foreshadowing cleverly, making us feel like we have an intimate understanding of Sheetal’s struggles. But with every twist, we – like Sheetal – discover just how little we know as the story unfurls like a lotus flower, each petal adding a complication connected to the shining centre until at last, at full bloom, we gain a profound insight about the relationships we have with those around us through Sheetal’s unique Hero’s Journey.

As much as I love the book, there were some parts that I felt lukewarm toward, such as where some details momentarily upended my suspension of disbelief. However, I won’t nit-pick at these because I don’t think my teenage self would have picked up on those issues. I would have been too busy enjoying the novel to really care.

More importantly, though, I wasn’t feeling the romantic subplot in this book. While I think that the romance between Sheetal and Dev is cute on paper, at the beginning of the novel, I felt more like I was third-wheeling on a date. Thakrar used the close third-person perspective, and since the most affectionate parts of the romance occurred in the first few chapters with little build up to it, I felt more like I was watching a couple I hardly knew going all in with their public display of affection. While this did make sense because their relationship was already well on its way by the time the story begins, I personally don’t think that Thakrar gave us enough detail to get invested. I also thought that there was an opportunity to build the romance up a bit more throughout the story, but then Dev just vanishes for most of the book before suddenly reappearing again near the end of the second act. Without something more tangible than Sheetal’s grumpy pining for him when he was missing, the romance fell flat for me, and I think that the story would be the same if Sheetal and Dev were just friends.

Even though I felt lukewarm about the romantic subplot, I genuinely enjoyed the story and the way Thakrar was able to wrap us up in her storytelling and ultimately surprise us with some of the twists in the latter part of the novel. I actually found myself wishing she had included some more details in some scenes because I wanted them to last just a little longer, even though the book is already long as is. I believe that if I had a little more background knowledge about Hinduism, I would have had a better appreciation for all of the intricacies Thakrar wove into the novel. There were quite a few cultural and mythological references that I understood, but I am sure that actual Hindu readers would appreciate it at a different level.

Conclusion

Star Daughter was a good book. I love the way it showed how messy relationships can be between individual teenagers and their extended family. Family can be so well-meaning at times, but that good-heartedness can sometimes raise teens’ anxieties in ways they don’t know how to express. I also loved the way the story gave me some insight into a part of Hinduism that I never considered, that being the Hindu interpretation of the cosmos and its followers’ place within it. While it had some logical issues and even though I didn’t care much for the romantic subplot, I still enjoyed the story as a whole.

I would recommend this story to any teenager who wants to learn more about Hindu cosmology or just wants to read about a teenage Indian girl learning to be herself amid the messiness of her life. Even if you’re like me and are several years removed from that stage of life, I think you will enjoy the story as well.

I’m genuinely looking forward to when Shveta Thakrar brings out a sequel to this book. If not, then I’m just excited to see what she comes up with next.

I’m genuinely looking forward to when Shveta Thakrar brings out a sequel to this book. If not, then I’m just excited to see what she comes up with next.

You can read an excerpt of Star Daughter online at https://bit.ly/2HOGrdK or by scanning the code below with your phone.

Nikita Blair is a speculative fiction and creative non-fiction writer. Her work has been featured in Moray House’s Ku’wai magazine, The Guyana Annual, the Stabroek Weekend’s Writers’ Room and the Commonwealth Writer’s blog. A collection of her work is featured on her blog, blairviews, where she writes book reviews, essays, and articles on topics of interest. Currently, she is completing her degree in Communi-cations Studies at the University of Guyana, Turkeyen.