In last week’s article, we referred to the sad state of public accountability at the beginning of 1991. The last set of audited public accounts to be produced and laid in the National Assembly was in respect of 1981. The Authori-ties had contended that technical difficulties involving the use of the main frame IBM 3/15 computer at the central Ministry of Finance affected the Government’s ability to produce the accounts for subsequent years. However, there were no alternative plans to resolve the problem, including the possible use of back-up data, if any, and/or using the accounting records of Ministries/Departments/Regions.

My proposals for a restart of the process involving a two-pronged approach were met with outright rejection by key Finance Ministry officials, despite support from the then Minister of Finance. That approach involved drawing a line between 1990 and 1991; and putting mechanisms and controls in place to enable the production of financial statements from 1991 onwards. At the same time, a task force is set up to reconstruct the accounts for the nine backlogged years. The rationale for this approach was that, based on historical trends, it would take six years to produce one year’s audited accounts to the Assembly, so that by the time we reached 1990, we would still have six years’ backlogged accounts to deal with. In this way, we would never be up-to-date in having audited public accounts of the country.

I could have taken the position that if the Authorities did not want produce the financial statements relating to the public accounts in order to discharge their stewardship responsibilities to the nation, it was none of my business. I could have remained quiet and continued merrily along with the other areas of my responsibilities. However, the broader interest took precedence over a minimalistic approach that would have no doubt earned me handsome superannuation benefits upon retirement 24 years away, and perhaps a national award, among others. There is an old saying about the Public Service which goes like this: Do little or nothing but stay within the rules; and you get all the promotion in offing, and end up with a handsome pension upon retirement!

My unstinting passion to improve public accountability in Guyana quite rightly got the better of me, especially in view of my six-month training at the U.S. Government Accountability Office in 1989 when I was Deputy Auditor General. Indeed, I wanted to make a real contribution in the field of my endeavour. I recall upon my return to Guyana going to work wearing a tie instead of shirtjac, and in all of my correspondence to government officials, I began by addressing them as “Mr.” instead of “Comrade”. Having been exposed to western democratic norms and values, it was indeed an act of defiance against the communist leanings and party paramountcy perpetuated by the late President Forbes Burnham. The late President Desmond Hoyte was not uncomfortable with the stand I took.

Today’s article concludes our discussion on the subject at caption.

Trends in financial reporting and audit in the pre-Independence period

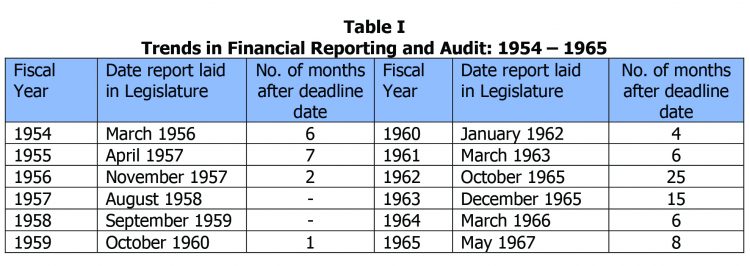

We had included in last week’s article a table showing the trend of financial reporting and audit for the period 1966 to 1981, which trend shows that it took on average six years to present one year of audited public accounts to the Assembly. This is in contrast to the pre-Independence period 1954 to 1965 when it took a little less than 16 months to do so, as shown at Table I:

One may legitimately ask: Why is it that we were unable to maintain the momentum that we inherited from the British in terms of our financial stewardship during the period 1966 to 1991? The answer appears to lie in my assertion that democracy and accountability are the twin sides of the same, as elaborated on last week.

Trends in financial reporting and audit in the post-1992

When the PPP/C Administration took over the reins of Government following the 5 October 1992 elections, I renewed my representation for a restart of the public accountability process based on the proposals I had put forward in 1991, as discussed in last week’s article. Contrary to the belief that it was that Administration which was responsible for the restoration of public accountability, the records will show that the Government merely gave the go-ahead to my proposals, and it was the Audit Office under my guidance and supervision that blazed the trail, despite all the difficulties and resistance shown.

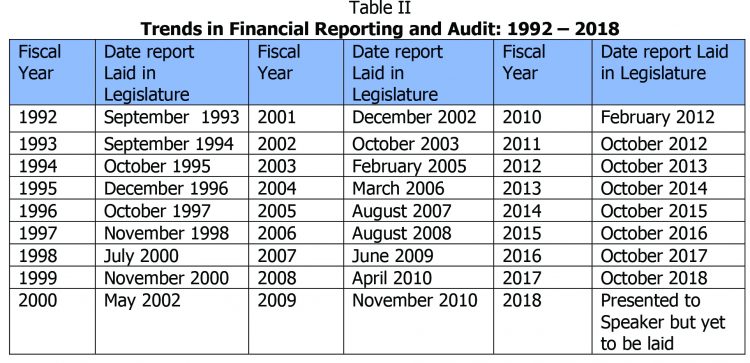

Public accountability was restored with effect from 1992. Since then, timely annual financial reporting and audit have become a regular feature of the operations of government, as shown at Table II.

The ten-year gap covering the period 1982 to 1991 would remain a significant blemish in Guyana’s post-Independence history of public financial management. The Audit Office had conducted preliminary audits for the years 1982 onwards, and the results were held in abeyance pending the submission of the financial statements relating to the public accounts. Considering the likelihood that those statements might not be forthcoming in the foreseeable future, I decided to use the proviso of the Financial Administration and Audit Act which allowed for the submission of special reports to the Assembly, should the Auditor General consider it desirable.

My decision was supported by a legal opinion from the Attorney General, and I was able to present to the Assembly preliminary reports for the years 1982, 1983, 1984 and 1985. I could not have proceeded further because my recollection is that another interpretation of the legal opinion suggested I could not do so. In any event, my focus was more future-oriented. Meanwhile, a task force was set up at the Ministry of Finance to reconstruct the accounts for the backlogged years but the effort had to be abandoned due mainly to a lack of documentation, and perhaps the urge or the passion to get the task done.

Trend in reporting by the PAC in the pre-1992 period

The only information that was available in relation to the work of the PAC in the pre-1992 period, was in respect of 1967. The related report was laid in the Assembly in 1984, some 17 years later. That apart, there was no evidence that a Treasury Memorandum was prepared and laid in the Assembly to complete the accountability cycle. I recall my early days as Auditor General when, as principal advisor to the PAC, I drafted the PAC reports for 1977-1979 and 1980-1981 using the verbatim records of the PAC meetings. The Chair of the PAC at that time was the late Reepu Daman Persaud who, I must say, displayed a good of confidence in my work. The related reports must have been laid in the Assembly prior to the 1992 elections, though I was unable to turn up evidence as to the exact dates when this was done.

As indicated in last week’s article, because I championed the cause for the restoration of public accountability, the new PAC had in effect placed me on trial so much so that I refrained from attending its meetings. The then Chairman refused to have me draft the PAC reports for 1992 and 1993. It was not until the late Winston Murray became the Chair, that I resumed the task of drafting the PAC reports, a practice continued until I demitted office in January 2005. I have read the PAC report for 2000-2001, which was presented to the Assembly in February 2006, the language used suggested that I had drafted the report.

I recall when I was on assignment with the UN Peacekeeping Operations in Africa, I had returned to Guyana in December 2003 for the Christmas holidays. I attended a PAC meeting at which there was discussion of the draft Audit Act that a consultant had prepared. The PAC was unable to make sense of it, and I volunteered to rework the document. This I did, and I presented the revised draft to the PAC before returning to Africa. It is this draft that formed the basis for the Audit Act 2004. There were, however, two modifications that the Authorities had made and with which I did not agree: the requirement for an additional audit to be conducted by an auditor other than the Auditor General where an agreement entered into between the Government and an international financial institution so dictates; and the Minister of Finance may request the PAC to cause an additional audit to be conducted by an auditor other than the Auditor General. Space does not permit to explain why these two provisions were inserted. Suffice it to state that since the passing of the Act, these provisions have never been invoked.

Trend in reports by the PAC in the post-1992 period

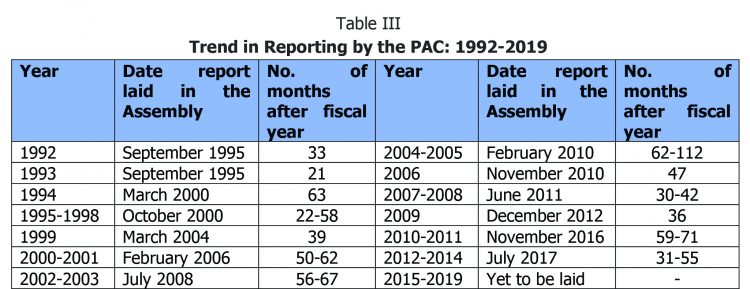

The Audit Office’s website has only three reports of the PAC in the post-1992 period: 2000-2001, 2007-2008 and 2009 although a total of 13 reports were issued to date. A search of the Parliament Office’s website was also not helpful. I therefore had to rely on media reports for the missing years to establish the trend in reporting by the PAC which I present in Table III.

Some final thoughts

It is the convention for the Chair of the PAC to be a former Minister of the Government. However, sitting Ministers are not normally included in the membership of the Committee because of possible conflict of interest, especially when the PAC scrutinizes the accounts of the Ministries and Departments for which they are subject Ministers. The Auditor General would also be hard-pressed to be as critical as he would like to be of a Ministry or Department, knowing full well that the subject Minister is sitting on the Committee.

The PAC needs to develop a strategy as to how to deal with the backlogged accounts in trying to bring its work up-to-date. Perhaps, it may be worthwhile to take a two-pronged approach with the full Committee examining the most recent fiscal year, and a sub-committee attending to the backlogged years.

Finally, while recognizing the role of the Auditor General, the Accountant General and the Finance Secretary as advisors to the Committee, it may be worthwhile for the PAC to seek further technical assistance from retired Permanent Secretaries who have demonstrated expertise in public financial management.