SYDNEY, (SciDev.net) – Researchers have developed a new and cheaper method of recycling used cooking oil and agricultural waste into biodiesel, and efficiently convert food scraps, micro-plastics and old tyres into valuable molecules used in medicines, fertilisers and biodegradable packaging.

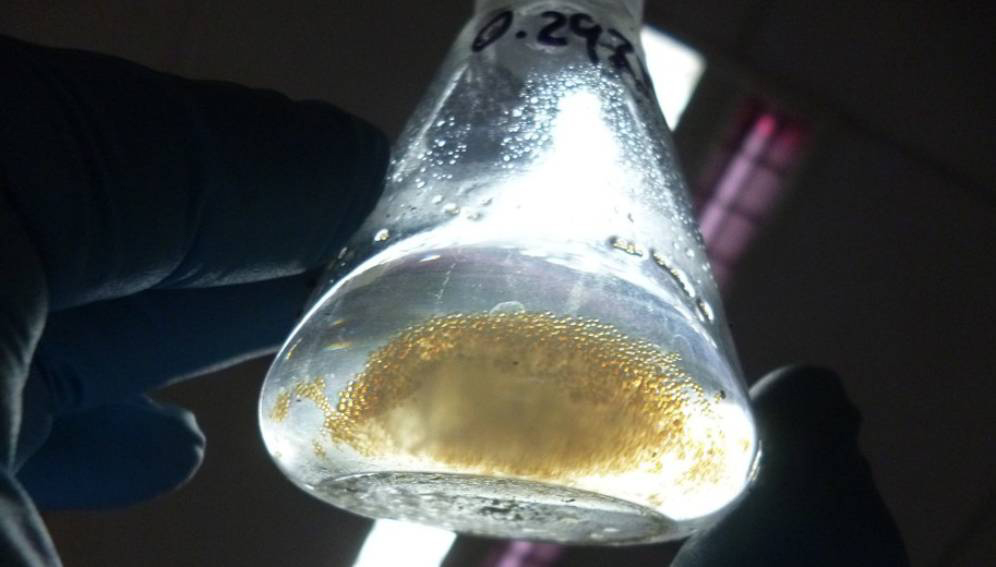

The highly porous, micron-sized ceramic sponge contains different specialised active components that accelerate chemical reactions, according to the research, an international collaboration led by RMIT University in Melbourne, Australia, published 26 October in Nature Catalysis.

Molecules enter the sponge through large pores, where they undergo the first chemical reaction, and then pass into smaller pores to undergo the second reaction with the help of nanoparticles.

“Our new, solid catalyst is cheap to fabricate, easy to recover, and reuse, from biodiesel, requires less energy and creates less waste for biodiesel production,” says Adam Lee, co-lead investigator and professor of sustainable chemistry at RMIT University.

“It also includes a built-in cleaning component that neutralises common contaminants. This allows the catalyst to cope with dirty oils, and to keep working for longer without needing to be replaced, offering a significant cost saving.”

The innovation has the potential to lift rural farmers and villages out of energy poverty — a current dependence on fossil fuels — by enabling them to produce their own fuels, the researchers believe.

Currently, huge quantities of agricultural waste, notably from cereal crops, are burned annually in developing countries, resulting in poor air quality, damage to health and contributing to climate change.

“The multifunctional catalyst offers a low-cost and low-tech route to recycle carbon contained in this waste — from rice husks and vegetable peelings to rancid used cooking oil — and advance towards a circular economy,” says Karen Wilson, co-lead investigator and professor of catalysis at RMIT University.

The research team is currently working to scale-up catalyst production from the gram to multi-kilogram scale to make it commercially available, and to create a range of similar catalysts tailored for different waste streams, for example, used cooking oil, sugarcane bagasse and vegetable scraps.

“We are hoping to bring our first catalysts to market in one to two years and reduce costs,” says Lee.

Zeenat Niazi, vice-president, Development Alternatives Group, a New Delhi-based social enterprise dedicated to sustainable development, says the research could be useful for Asian countries.

“This research offers interesting possibilities for the South and South-East Asian region where low-grade, mixed food-stock … is available from agro-wastes, used cooking oils and waste plastics in rural and urban areas,” he tells SciDev.Net.

“However, this requires research findings to be tested through practical ground application to understand the benefits and trade-offs to farmers and small entrepreneurs.”

This piece was produced by SciDev.Net’s Asia & Pacific desk.