Introduction

Today’s column reviews estimated Government of Guyana (GoG) revenue and related benefits arising from its International Oil Companies (IOCs)-led oil and gas sector. Considered carefully, Guyana’s expected revenue and related benefits are likely to be principally a function of six variables. These are: the fiscal rules that govern the various Production Sharing Agreements, PSAs; the level of petroleum discoveries; the projected daily rate of oil production (DROP); oil and gas prices; existential risks and challenges facing the successful commercial emergence of the sector; the capabilities of the IOCs; and, the industry’s unit cost-price relation.

As readers are aware, the principal elements of the PSA allow for: 1) a signature bonus, US$18 million; 2) a 2% royalty; 3) cost-recovery provisions and production sharing; 4) pay on-behalf income tax provisions; 5) miscellaneous taxes and revenue imposts; 6) rental charges and fees; 7) profit-sharing; and 8) domestic market obligations (DMOs).

Incomplete contracts

As I had observed two years ago in this column, the Nobel Prize winning economic theory of “incomplete markets” posits that all Parties to Guyana’s PSAs have rational incentives to re-negotiate these contracts, once underlying conditions of the country’s oil and gas sector drastically change. This radical observation holds true, despite the public posture of all the Parties not to re-open negotiations because of the sanctity of contracts. From the perspective of the IOCs, their reasoning is based on the need to optimize profits for their shareholder. And, from the perspective of the GoG, it is whether the financial and social benefits obtained from the sector are consistent with its risk profile and preference function.

From this standpoint, the performance outcome that perhaps matters most to the GoG, is the division of net cash flows between the IOCs and itself. This is termed Government Take. That take is essentially the product of a negotiated outcome. As such it is not an economic statistic, but instead a fiscal metric! Because of this feature, comparing the take of different projects as well as across countries can be exceedingly difficult, if not a misleading exercise. Several other considerations also apply. Thus, to be accurate, the take has to be measured at both the project and country level, as well as ex ante and ex post. The major impediment facing such efforts is usually data confidentiality for commercial reasons

Government Take

A standard definition of government take is “the percentage of a petroleum pre-tax project’s net cash flow adjusted to take into account any form of Government participation. The take can be calculated in discounted or undiscounted value” (S. Tordo, 2007). As indicated above, this is a fiscal metric; but as also indicated in earlier columns, private contractors rely on economic indicators to evaluate projects, for example: net present value (NPV) of the project’s cash flow; the internal rate of return (IRR), and the profitability ratio (PR).

Noise & Nonsense Agendas

Government take has other limitations worth noting. For one, it is not neutral with regard to the impact of oil price changes on it. Indeed it varies with both oil prices and IOC profits. For accuracy it should therefore be calculated over the expected life cycle for the oil field. The reason being that, when the cost of production falls below the recovery cost limit during the project’s life the amount of profit oil to be divided between the IOCs and the GoG increases. Unfortunately, the noise and nonsense frequenting the local print and social media ignore this caution, thereby yielding fake low estimates of GoG Take to serve their agendas. Furthermore, other Government benefits accrue; namely, 1) regulated local content requirements (LCRs), 2) Research and Development (R&D), 3) technology transfer, and 4) skills training and further education.

Zero-Sum Game?

Serious analysts strive to ensure that the division between governments take and IOC’s profit is not portrayed as a simple zero-sum game. That is, one in which one party gains only at the expense of the other. As noted before, IOCs focus on the NPV, IRR or PR. Consequently, it is quite possible for the value accruing to both groups to rise together. This possibility however, does not mean there is zero likelihood of a zero-sum game situation occurring.

Discussion of GoG priorities for spending, along with Production Sharing Agreements’ (PSA) fiscal rules will not be repeated in this column. The tricky consideration for readers to note here is the treatment of recovery cost allowed to IOCs. As noted, such treatment depends in large measure on the maximum set in the PSA (75%), along with the variable life-cycle of petroleum fields.

Risk

Worldwide, PSA arrangements have proven to be risky. They do not guarantee outcomes, because of far too many known and unknown, unknowns embedded in the petroleum sector. The division of benefits between governments and IOCs laid out in PSAs, is dynamic and changing over time. Guyana’s PSAs, like others worldwide, is therefore, likely to be amended/changed/re-negotiated through time, albeit at an unknown cost.

PSAs strive to attain multiple objectives. They are not exclusively directed at revenue-sharing. Thus, Guyana’s addresses concerns like: protecting the nation’s wealth against adverse environmental effects; promoting efficiency; and, establishing “local content” requirements, LCRs.

.Empirics

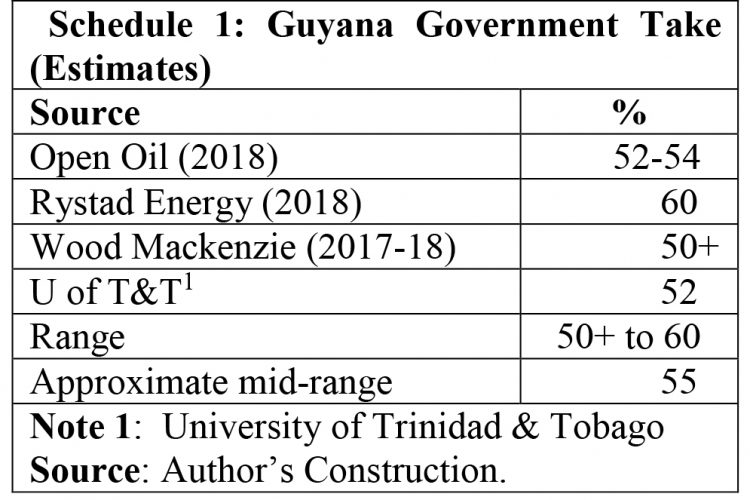

In earlier columns I drew attention to four estimates of GoG Take ratio. These are from Open Oil, Wood Mackenzie, the University of Trinidad & Tobago and Rystad Energy. Schedule 1 reveals the results. These range from 50+ to 60%. My belief is the mid-point of the range for these estimates represents a reliable predictor for GoG Take. That is 55%.

Conclusion

In Q3 2020 Wood Mackenzie released an updated estimate of Guyana Government Take. I’ll review this modeling effort in a coming column where I wrap-up discussion of this topic.