Albion Wilds

Dear Solitude!

Where peace and concord dwell,

Whose smiling beauties quell

The soul’s inquietude.

O fold thy child

Unto thy bosom warm;

My care-worn spirit charm

With music undefiled!

[. . .]

How sweet at morn,

To see high heaven’s arch,

Made glorious with the march

Of Phoebus’ bright return;

To see his rays

Come peeping through the trees,

And hear rich symphonies

Ring through the woodland ways!

In heat of noon,

How sweet it is to lie

‘Neath leafy canopy

And hear the wren’s shrill tune

In ripples slide,

Like a small stream that flows

Over a pebbly course

Down from a mountainside!

At eve how sweet

To see the herons home,

And out the young birds come

Their parents glad to greet!

[. . .]

I love this grove,

Its birds and flowers and woods,

For o’er these beauties brods

The Omnipresent Love.

– J W Chinapen

Tales Under the Sankoka Tree

A moonlight scene, a group of indentured

Indians under a peepal tree. Idle chat…

Songs of Ganga and Jamuna, Mathura and Brudabam.

As the haunting melodies swelled into the air

Visions of dear scenes came to these hard men

And many a teardrop trickled down wet cheeks

And deep sighs swelled each bosom.

They saw again their boyhood’s haunts and lived

Again those happy times. They, overtaken as by a spell

Became oblivious to the passing of the hours

Till suddenly a loud long whistle crashed

Into the still air – the factory’s whistle

Calling Coolies to their tasks.

The visions vanished.

But memory still clings to that delightful spot,

[. . .]

Games, too, we had – card games

Biska, troop-chal and gann.

When card prints are discernible no more

Songs and tales ran far into the night…

– J W Chinapen

Diwali is one of the wonders of Caribbean culture. It is among the great festivals brought to the region by indentured immigrants from India, one that restores its original glory; rekindling its triumphant lights after landing on distant shores as if to defy the effects of a kala paani. As it is known today, it is a treasure trove of Hindu culture that has become indigenous to local conditions in Guyana and the Caribbean.

Although somewhat muted this year because of the restrictions imposed by the prevailing pandemic, Diwali illustrates significant factors about culture among Hindus in the Caribbean. One hundred years since the end of indentureship and it still shines bright, confident in an environment in which it has evolved, ever responding to local influences while retaining its identity and character. In this, there are interesting comparisons with East Indian poetry that emerged since 1920 in Guyana.

In 1894, a very impactful wave of intellectual leadership was initiated by Berbician Joseph Ruhomon, who gave a lecture and published its text, signalling a strong rise in Indian cultural awareness in British Guiana. The publication was titled To India, the Progress of Its People At Home and Abroad, and How those in British Guiana May Improve Themselves. Among other things coming out of this were cultural clubs and poetry. One of the ironies is that the culture that Ruhomon saw lacking among the immigrants was the culture from India, not that of British Guiana. While there was a rise of poetry among the immigrants, it advanced neither the literature imported from India nor anything indigenous to Guyana.

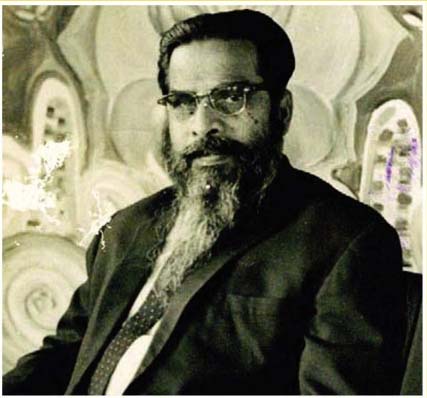

A number of East Indian poets had emerged in the colony, taking the discipline seriously and publishing their work. Among them was Ruhomon himself, along with his brother Peter Ruhomon, W W Persaud, J W Chinapen and C E J Ramcharitar-Lalla. They were published in a collection of verse, the first by East Indians in Guyana, titled Anthology of Local Indian Verse (1934). It was edited by Ramcharitar-Lalla.

Further ironies abound because it is believed the anthology was released as a response to Guianese Poetry 1831 – 1931 (1931), edited by N E Cameron. This book was of predominantly black poets and included no East Indians. Yet, apart from Ramcharitar-Lalla, himself, the work contained in the 1934 publication could hardly be regarded as reflective of local Indian verse. The editor’s poem “The Weeding Gang” was alone in capturing the local estate existence and culture. It is the kind of poem that did not begin to emerge in Guyanese East Indian literature until the 1970s, which included work by Rajkumari Singh, and most prominently by Rooplall Monar in the 1980s. The only other member of that group to write anything truly local was Chinapen, though he did not publish that work in the anthology or even in his own collection in 1961.

The verse was very typical of its time and of a practice known right across the Caribbean in the 1930s. It is an imitation of English Romantic, nineteenth century and Victorian poetry. Chinapen’s “Albion Wilds”, taken from the 1934 Anthology, is representative of that type. His other poem, “Tales Under the Sankoka Tree,” is from the collection, They Came In Ships: An Anthology of Indo Guyanese Poetry and Prose (1998) edited by Joel Benjamin, Lakshmi Kallicharan, Ian McDonald and Lloyd Searwar, and published by Peepal Tree Press. We learn from that collection that Chinapen took the trouble to expunge from his work a number of references which were either Indian/ Hindu or local Guyanese. Further, he did not include the “Sankoka Tree” poem in his only published collection Albion Wilds.

What is characteristic about the imitative poetry is that it avoided anything culturally or linguistically local, with a preference for the English. “Albion Wilds” contains linguistic expressions which were considered “poetic” at the time. It was only with the rise of modern (Modernist) poetry in the 1920s that this kind of archaic versification was jettisoned. So Chinapen uses “o’er”, “‘neath”, “thy”, “canopy” and other archaic forms in copy of the poetic language of previous centuries. The sun becomes Phoebus from classical mythology, another borrowed feature from the Greek and Roman traditions.

In contrast, “Tales Under the Sankoka Tree” does, in fact, represent Plantation Albion or the Corentyne village of that name. The references are true to the environment and much more in line with the poetry of local Guyanese Indians. Knowing that Chinapen was from Berbice it was easy to think that the poem “Albion Wilds” described the sugar estate village. But on reading the poem one remembers that “Albion” is also an ancient name for England. The poem’s imitative landscape refers to “a small stream that flows over a pebbly course down from a mountainside”. There is no such geography on the wide, flat Corentyne Coast. There is nothing in the poem that tells us it is not really about ancient England.