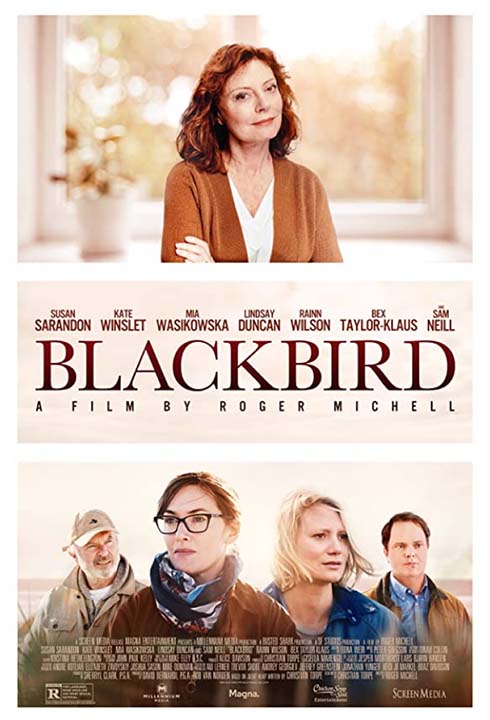

![]() “Blackbird,” Roger Michell’s remake of the Danish drama “Silent Heart” (both written by Christian Torpe), is not what you would expect from a film that ends with euthanasia.

“Blackbird,” Roger Michell’s remake of the Danish drama “Silent Heart” (both written by Christian Torpe), is not what you would expect from a film that ends with euthanasia.

The euthanasia is no spoiler. Instead, it is a plot-point baked into the film and revealed early on. Lily, matriarch of a dysfunctional family, invites her children and their families to her beach house residence for a final weekend. She intends to enjoy a convivial weekend with them, and her husband, as a farewell of sorts, before she ends her life. The decision is in response to her likelihood of turning into a vegetative state because of a degenerative disease she’s living with.

It will be to the surprise of no one that this carefully pitched weekend will quickly devolve into a case of family flare-ups and upheavals. But, what’s most striking about “Blackbird” is that even as it pitches the familial tensions as realistically exhausting and complicated, Michell’s film remains strangely easy-going for a film that centres on death. This quasi-avoidance tactic might be indicative of the characters’ own inclination towards misdirection.

Lily, as played by Susan Sarandon, hides her sharp self-awareness behind a graciousness that is effortful. She’s aware that her younger daughter, Anna, is a bit of a scatterbrain. And she’s equal parts grateful and exasperated at the suffocating devotion of her older daughter, Jennifer. The mother-daughters trio is joined by Lily’s reticent husband, her best friend, Anna’s non-binary kind-of-a-girlfriend and Jennifer’s husband and son. It’s a full-house for a grand farewell as the group participates in a faux-Christmas celebration to satisfy Lily. As Michell and Torpe set up the scene, we keep waiting for things to crack. And, oh how they crack. Into many pieces.

Lucky for “Blackbird”, Michell is able to navigate through the varying tones and foci that the film thrusts at the audience. From moment to moment, “Blackbird” flirts with comedy, melodrama, chamber-drama, satire and even cringe-comedy but it manages to retain a fluidity that calibrates itself to the recurring tenets of this family’s love – and resentment – for each other. Like a typical ensemble drama, the cast is split up into groups as plot-points begin to compete for attention – some more compelling than others. Sarandon plays best with others, an essential aspect of the magnanimity of Lily that must define their acquiescence to her. Kate Winslet, as the fussy Jennifer, is best-in-show, though. It’s a role that does not require heavy lifting, but she shades Jennifer’s prickliness in interesting ways that turn a potentially tetchy woman into something with glimmers of surprising self-awareness.

Torpe’s script is markedly low-key. Even as he creates situations that might potentially teeter into excess, the screenplay keeps incredulity at bay. There’s an occasional glibness undergirding the quips but in its most incisive moments his words articulate an awareness of mortality and sadness that feels valuable.

The film is strongest when the entire cast comes together, and the final scene is a thoughtfully constructed cap even as its revelations of secrets feels almost too predictable. It’s impossible to indict “Blackbird” for its almost dogged earnestness, because its faith in the goodness of its characters feels too sincere to decry. One could argue, maybe even convincingly, that “Blackbird” feels altogether too warm and diffident for a film that centres on some dark and hard-hitting themes. In a way it speaks to the way the film is ironically as unwilling to focus on the darkness as the family at its centre. But another, more thoughtful interpretation might see the potential for charm in the way Michell’s film is open to examining these people with gentleness.

It feels counterintuitive to label a film about death as escapist, but the hopeful tenderness of “Blackbird” if not revolutionary, feels quietly affecting. Even as its argument on euthanasia is almost non-existent, the film’s focus on Lily’s agency within her situation makes “Blackbird” a sensitive rendering of the struggle of growing old. It’s inevitable that the big names of the cast set up expectations of the film’s profundity that the smallness of Michell’s canvas may not readily live up to. But, in watching “Blackbird”, I could not help but think how unlike much of contemporary cinema it feels like. Its familiarity is the familiarity of something that feels archaic. Those hints of the archaic do not feel like a crutch, but instead present the film as a pleasant reminder of the boundlessness of family. There is death in this beach house. But, the film itself is overflowing with life.

Blackbird is available for rent and purchase on Prime Video and iTunes.