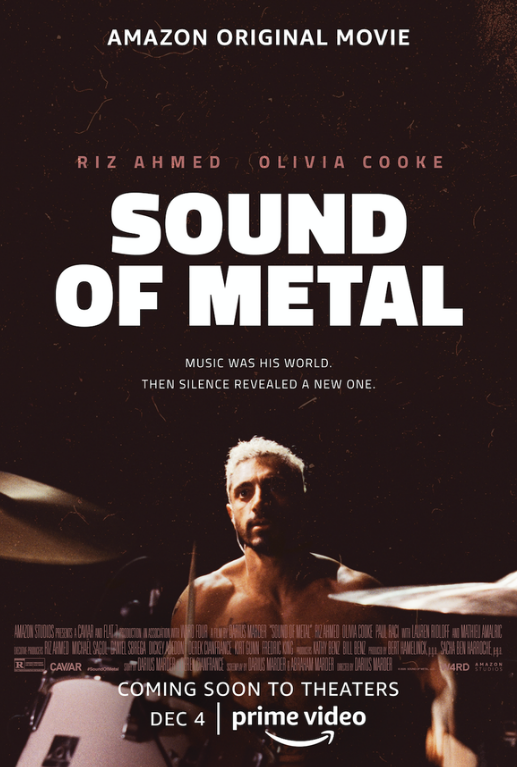

![]() In many ways, Darius Marder’s “The Sound of Metal” feels like a decisively singular story. The film traces the struggle of punk-metal drummer Ruben (a devastating Riz Ahmed) as he acclimates to the loss of his hearing. Films about deafness are rare, and Marder’s presentation of the ways Ruben’s deafness intersects with Ruben’s talents and love for music makes for a sharp and original focus. In many ways, though, the singularity at work in “The Sound of Metal” feels like it’s in direct conversation with larger contemporary preoccupations of the ways loneliness and isolation feel like defining symptoms of living in the 21st century.

In many ways, Darius Marder’s “The Sound of Metal” feels like a decisively singular story. The film traces the struggle of punk-metal drummer Ruben (a devastating Riz Ahmed) as he acclimates to the loss of his hearing. Films about deafness are rare, and Marder’s presentation of the ways Ruben’s deafness intersects with Ruben’s talents and love for music makes for a sharp and original focus. In many ways, though, the singularity at work in “The Sound of Metal” feels like it’s in direct conversation with larger contemporary preoccupations of the ways loneliness and isolation feel like defining symptoms of living in the 21st century.

There’s a recurring aesthetic motif in the film. A wide-shot of the surroundings will suddenly encroach on Ruben’s face – emphasising Ahmed’s penetrating gaze. The first moment it happens, the opening scene, it seems to be simply a visual representation of his focus on his craft. But as the film goes on – quickly introducing us to Ruben’s imminent deafness – the motif becomes tied to the sound design. Daniël Bouqet’s camera aggressively traps Ahmed’s face and body within the frame and the sound design – increasingly experimental as the film goes on – heightens the schism. Silence and muffled noises representing Ruben’s world, and then a sharp and disorienting shift to the loudness of the world around him. A world that he is emotionally removed from. That emotional remove becomes the fulcrum of Marder’s thematic concerns.

The early moments establish the central dynamic that will define Ruben’s arc. Ruben and Lou (Olivia Cooke), his professional and romantic partner, are part of Blackgammon – a punk rock duo. She sings, he drums. Their chemistry early on, sincere with tinges of something slightly like desperation, suggests that this is a couple that has had their fair share of holding on to each other through tragedies. A later revelation that they began their relationship when Ruben stopped being a heroin addict informs what comes earlier. Discussions of a tour and an album are interrupted by Ruben’s deafness which seems to happen all at once. Hearing loss oftentimes happens incrementally, and there’s a deft ingenuity in the script (Marder cowrites with Abraham Marder from a story by Derek Cianfrance) which rather than spending the first act on Ruben losing his hearing little by little, thrusts us into complete silence within minutes.

And that silence feels like the worst thing for Ruben, who seems to use the loudness of the drums as a replacement for drugs. The intensity of his gaze as he plays is penetrating. The only solution, for him, is surgery to partially restore his hearing. That hope is placed in firm contrast at the deaf commune that he enrols in, to acclimate to his situation. Ruben’s atheism, restlessness and focus on retaining some of his hearing presents an ideological schism between approaches to deafness. At the commune, deafness is not a limitation to be fixed and Ruben’s continuous yearning to hear the music again puts him at odds with this.

Marder presents Ruben’s story as a character study that balances his directorial vision and Ahmed’s anxious performance. Ahmed’s performance is one of the year’s best, giving him a platform to present the manifestations of anxiety and distress. It’s a performance that feels sharp with authorial intent, shaping the film as much as the script and the direction. For long stretches, Ruben’s silence defines his characterisation. Instead, Ahmed’s body nakedly tells us all we must know. It’s there in the panicked intensity of his gaze. In the way that his body seems so tightly wound that the smallest surprise might send it reeling. It’s in the way that he holds his head puts him at both a physical, and emotional, remove from those around him. There’s the anxiety and uncertainty that runs through the film, but there’s also the increasing sense of loneliness. Even as Marder marries Ruben’s plight to strains of solidarity with the deaf community, his own personal demons find him unable to see the world as anything centred in togetherness.

There’s a late scene where Ruben gives his philosophy of the world – he paints a bleak picture where nothing matters and the only thing to fall back on is individual desire. There’s an agitated cadence to the way Ahmed delivers the lines, somewhere between desperate and tearful. We’re not sure if he’s trying to convince the listener, or us. Ruben’s deafness places him on the outside looking in, and as “The Sound of Metal” goes on, we come to realise that what he fears more than his loneliness is having to depend on someone who may not be there for him. Within that context, the two most poignant moments – one a rejected request from a mentor, the other a melancholy bedroom conversation – focus on a man desperate for connection, but also desperate to remain alone, for his own safety.

It’s here that “The Sound of Metal” is most thoughtful and seeking. The film’s presentation of deafness is instructive, but occasionally falls into too black-and-white a representation of the divide between ways of thinking about deafness. The commune’s stance on deafness as something that does not need fixing dominates the film, which seems unable in the last act to match Ruben’s sincere desires with another perspective on hearing loss. It’s why the specificity of Ahmed’s work helps the film. By emphasising Ruben’s own individual struggles with isolation, the film becomes more impactful as part of a cultural conversation on psychic isolation. The film’s final shot does not seek to resolve that preoccupation, instead leaning into the inevitability of the contemporary crisis of being alive. No matter how many connections are forged, there’s a sense that the modern world is built on a state of unrelenting isolation. It’s a bleak outlook. But Ahmed’s devastating performance is a gift that makes it all worth it.

The Sound of Metal will be released on Prime Video on December 4.