By Alim Hosein

(The following is a revised version of an illustrated talk presented at Moray House Trust, on Saturday, November 7, 2020)

of the interesting things about Ron Savory is that while he was an active artist, and an innovator in Guyanese painting, very little critical work has been done on him. This is true of all Guyanese artists, but some have received scholarly attention in Guyana and even abroad, such as Stanley Greaves, Philip Moore, and Aubrey Williams.

Savory felt this lack of recognition, as his niece Denise Savory-Archer wrote in a posthumous tribute to him in 2019: “He always spoke of the lack of appreciation for his art throughout the

Caribbean. He always felt under-appreciated!” Savory also discussed it himself, as he did during a talk at the National Gallery, Castellani House, in 1996. One example he gave was that in 1969-70, the newly-opened Pegasus Hotel painted over a mural he had been commissioned to do.

This is a very interesting situation, since Savory was intellectually active and moved in a circle of people who were the young intellectuals of the day. Savory also was a very active and passionate man of many activities. Apart from being an artist, he was also involved in broadcasting. He was a civil servant, musician, basketballer, theatre lighting and sound technician, radio producer, and jazz musician, among other things.

Yet, it is as an artist that he is best-known in Guyana, and he eventually gave up other jobs to focus on art. So we can imagine how difficult the lack of recognition was for him.

Life

Ronald Cecil Savory was born to Clarine Dewar and Neil Savory on November 21, 1933. He was the youngest of 4 boys. He had his secondary education at Queen’s College, and graduated in 1951.

After leaving school, he did several jobs and eventually joined the public service, working at the Lands and Mines Department. In October 1959, he was posted to Kamarang in the Mazaruni as a clerk to the Assistant District Commissioner, and he worked there until 1962. That was the major turning point in his artistic life. In 1960, he married Sheila Hancock. After Kamarang, Savory worked in Lethem between January and September 1964. He then moved back to Georgetown, resigned from the civil service, and was appointed an Administrative Officer with the British Council in 1965.

In 1968, he benefited from a British Overseas Development training stint with the BBC, during which he worked with engineers, architects, and museum curators. When he returned to Guyana, he worked for the Guyana Broadcasting Service (GBS), a local radio station, from 1968 to 1974.

Savory was involved in the Theatre Guild and assisted with lights and sound. He had a show on the radio where he played and talked about jazz. He not only loved listening to music, he also played the steel pan. In 1956, he was part of the Symphonia Steel Band in the production of Cecily De Nobrega’s “Stabroek Fantasy”.

He was a part of the Taitt Yard, a loose group that congregated at Taitt House (now Cara Lodge) including Helen and Clairmont Taitt, Cecily De Nobrega, Hugh Sam, Michael Gilkes, Ken Corsbie, Ricardo Smith, Marc Matthews, Stanley Greaves, and others. Taitt House was an informal intellectual centre which nourished these young people who were the literati of 1950s-70s Guyana.

Savory nevertheless remained the artist during these different phases. He sold his first painting in 1958, and he had exhibitions and shows almost every year. He was involved with the British Council and the USIS Library and his shows were often held there.

He had his first one-man exhibition at the Guyana Society 1959. He showed works from his time in Kamarang in a 1962 exhibition along with Michael Leila, Emerson Samuels, and Stanley Greaves at the Bookers Universal Building (now Guyana Stores, at Main and Church streets). In 1967, he was invited to hold an exhibition at the Carlart Gallery in Port of Spain.

He also did shows in Sussex, Dominica, Barbados, St Lucia and, of course, in Guyana. In 1970, he was invited to coordinate the mounting of the art exhibitions for the first Carifesta, which was held in 1972. This meant mounting 36 exhibitions across Guyana. This he did along with 14 other Guyanese artists.

Savory also had stints teaching art at the Guyana School for the Arts (run by Helen Taitt at Taitt House), St Margaret’s, and the Cyril Potter College of Education. He also wrote about, but did not publish, his experiences and those of other artists.

At some point, according to his niece, he “decided it was time to realise his dream and become a full-time artist”. This decisive move happened in 1974, when he resigned from the GBS. He continued working prolifically, exhibiting at regional festivals and events such as Carifesta, Art Creators (Trinidad), Carib Art (Curacao) and Domfesta (Dominica), and doing commissioned work.

In January 1980, he left Guyana and moved his family to St Lucia. He opened his studio on a hill on L’Anse Road. But he maintained contact with Guyana. In the 90s he was contracted to create artwork to be hung in the Guyana Bank for Trade and Industry (GBTI) on Water Street in Georgetown. The artwork is still there on the walls. In 1991, he was commissioned to execute 12 original and 327 prints for the Pegasus Hotel in Guyana. These works were hung in the western wing of the hotel. He returned to Guyana in October 1993 for a two-week exhibition at the Hadfield Foundation in Georgetown. He returned again in June-July 1996 for an exhibition at the

National Gallery, Castellani House. There he did an on-the-spot painting based on a poem read by Ian Mc Donald. His last exhibition in Guyana was “Evocations on Caribbean Literature Revisited” at the National Gallery of Art in March 2010.

Savory died in 2019 in St Lucia.

Context

Savory came of age at the moment when Guyana was itself coming into its own. There was much local political activity, including the first fully-elected government in 1953, the removal of this government 133 days later, and the split in the PPP in 1957. There was much activity among the working class, and businesses and the civil service were transitioning to Guyanese management. In the background to all this was independence from Great Britain.

A local intelligentsia was developing and local writers such as Martin Carter, A J Seymour and

Wilson Harris had been writing and publishing a new kind of Guyanese poetry since 1950.

Seymour had founded the journal Kyk-Over-Al in 1945. Jan Carew published Black Midas and The Wild Coast in 1958, and Wilson Harris published Palace of the Peacock in 1960.

It was also the time when Guyanese began to emerge and develop as nationally-known artists. This movement had started when expatriate artists and art-lovers created the British Guiana Arts and Crafts Society (BGACS) in 1931. This attracted local people of talent and out of it eventually came the Pioneers of Guyanese Art, including artists such as Hubert Moshett, E R Burrowes, Reginald Phang, Vivian Antrobus, Sam Cummings, R G Sharples.

The Guyanese artists avidly took up painting in the style of European landscapes. From 1944, the British Council entered the picture and began providing art materials and magazines, and bringing artists and critics to Guyana to give talks. The locals also began to diverge from the

European style and developed their own landscape and local subject matter, and also began to use new techniques and styles of painting learnt from the talks and magazines.

The BGACS held annual exhibitions, and as interest in art grew, local people formed their own art classes such as the Guianese Art Group (around 1945) and the significantly-named Working People’s Free Art Class (1948) started by Burrowes. These classes attracted and nurtured young locals and helped create the second generation of Guyanese artists.

Savory was part of this second generation. He joined the Working Peoples Art Class in 1957, and was among the many brilliant people who made up the second generation of Guyanese artists. This group included Marjorie Broodhagen, Basil Hinds, Edna Harte, Denis Williams and later, Savory, Greaves, Donald Locke, Michael Leila, Aubrey Williams, and Emerson Samuel.

He was active in a range of arts and activities, and had a circle of young friends and intellectuals who were among the cream of the crop of Guyana in the 1950s-70s: the Taitt House group including Corsbie, Matthews, Gilkes, the Taitts, Sam, Greaves, Leila, Locke and others. These were the people who were creating Guyanese innovations in theatre, broadcasting, literature, music, dance, and art, and we see in Savory’s paintings a similar, innovative response to the idea of a Guyanese nation and culture rooted in the land itself.

Art

Savory held his first solo exhibition in 1959, and his subjects were “…stevedores, rural landscapes, figures washing in the creeks, and flowers…”. But his art underwent a profound change after he encountered the Guyana jungle in 1959. He showed works from his time in

Kamarang in a 1962 exhibition along with Leila, Samuels, and Greaves at the Bookers

Universal Building. One of his early interior paintings, Kamarang, shows the continuing interest in people as in his earlier work. In this painting, his subject is people scratching out a living through backbreaking labour. He depicts them in dark brown, half-naked. He unromantically captures their poverty, their dreams, and their strength. He uses a rough, scratched technique to convey the harshness of their lives. In the interior, he had seen and was fascinated by the landscape and the petroglyphs at Imbaimadai.

He developed a new and personal style of painting, and he began using the Imbaimadai Petroglyphs in his work. Savory is usually credited with being the first to use indigenous art in his work. But this is debatable since his contemporaries also realised the cultural value of the petroglyphs. Some used them in their artwork, most notably Greaves (from around 1954), Locke, and Williams. But these artists eventually realised that they could not authentically sustain the use indigenous art. In his use of indigenous motifs, Savory did not just put them into his paintings but tried to use them as part of his composition of the picture. As seen in Bowman, the lines making up the figure also divide up the picture plane into different sections, and they also impose a grid of order on the more turbulent depiction of the river and jungle. Of course, this is a parallel to what the bowman actually does – he guides the boat through the treacherous water, thus allowing it to pass safely.

Another major change was that the interior landscape itself had a profound influence on Savory. In an interview I did with him in 1996, he said it was “…a culture shock which I took a while to recover from. This was a landscape which was basically dwarfing man. Man was not important as far as I could see…”. From this shock flowed a number of series of unique paintings. One of the earliest of these is the “Canopy” series. In another series, he painted the edges of creeks where roots, fallen branches, vines, and other plant debris accumulate. This is the “River Bank” series.

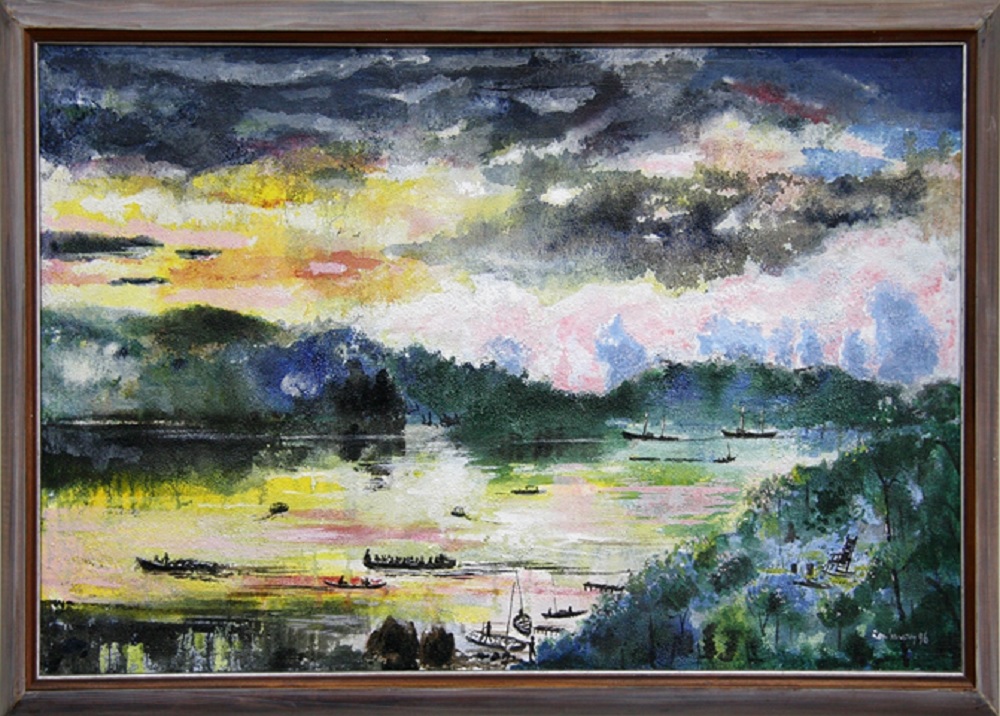

Because of the jungle experience, light, colour, space, form, and texture became radically different for Savory. The already-inherent expressionist tendencies in his works came to the fore. Form and colour were placed on the canvas not to simply depict a landscape, but to express it. The human figure, which had been a subject of his, almost totally vanished from his work. The work is now overpoweringly focused on land, water, sky, vegetation, rocks, light, shadow, and colour.

There was another development in his work after he moved to the Rupununi in 1964. Here, the additional challenge was the hugeness of the landscape. His paintings began to increase in size, as if to encompass the huge landscape.

And, as Greaves observed, one could well imagine compositions extending beyond frames.

Collaborations

From 1982, he began a spiritual collaboration with Caribbean writers. For example, the exhibition he held at Castellani House in 1996 featured 16 paintings inspired by McDonald’s collection of poems entitled Essequibo. It was at this exhibition that he did the impromptu painting of “It is good to look out at great rivers” simultaneously as McDonald read the poem. He also created paintings influenced by the poems of Seymour and Carter and the works of Edgar Mittelholzer, Naipaul, Walcott, Brathwaite, and others.

Another major source of inspiration came from non-literary writers. He was also very interested in the culture of pre-Columbian America, and the African influence on these cultures. Two major influences were Guyanese historian Ivan Van Sertima’s They Came Before Columbus (published 1976) and Lennox Honeychurch’s The Caribbean People (published 1995). One of Savory’s series of paintings, called Alphabet Bamoun, explores the similarities between African and Amerindian art.

Technique

Another aspect of Savory’s art is his technique. From the start, he was quite a technician who was interested in the possibilities of the paint medium itself. As he developed, he used paint in different ways – underpainting, heavy surface application, over-painting, scratching, thinner flat areas of colour, and so on.

His early technique is notable for his use of impasto. He learnt this heavy use of paint from his early mentor, Burrowes, but also from articles on such technique being used in Art Therapy shown to him by another early guide, the psychologist Dr Taitt of Taitt House. He also deliberately added sand and grit to his paintings to create real texture, but this was sparked by a happy coincidence after one of his canvases fell and picked up some dirt. He also used a scratching technique to create real texture on the canvas.

During the Rupununi years, he developed another approach, which he called “aerial landscapes” – scenes of the interior from a high vantage point. In these, the painting was looser and softer.

In later paintings, he used paint more thinly in flat areas of colour, but in conjunction with other techniques. He did not entirely abandon his impasto and scratching techniques.

In St Lucia, he continued the styles he developed in Guyana. In the different landscape there, his subject changed to the flora and landscape of the island, but the passion for light and colour remained. His painting techniques continued to develop, and his colours became brighter. He also created collages, and collage-like paintings.

Even when Savory left Guyana, his artistic vision continued to be what it was in Guyana. He saw his experience in Guyana as fundamental. He explained, in a 1993 interview, that the

Guyana hinterland, “…is where the whole idea of my artistic experience really and truly began. I don’t think there could ever be an end to the experience. I don’t see the possibility of finishing with it”.

Contribution

Savory changed the concept of landscape painting in Guyana. He was among the first to make the hinterland/landscape his subject, and to do so for a long time – it was not just a passing phase or a theme. He was consistent, persistent, and productive in doing so. One other painter who had made the hinterland his subject was Eddie Fredericks, an indigenous artist of the 1950s – 1960s, but his interest was in depicting the life and activities of the indigenous people in a realistic manner. Other, artists such as Ivan Forrester (although he was not as prolific as the other artists mentioned here), Williams, and later, artists of indigenous parentage – mainly Stephanie Correia, George Simon, and the Lokono Artists – made powerful use of the hinterland influence.

Savory’s work is sometimes close to abstraction, but it is not abstract. We can make an interesting comparison with his contemporary, Williams, whose work is abstract. Savory and

Williams pursued similar themes, ideas, and interests. Both were fascinated by the hinterland, both were passionate about American and Caribbean pre-history, and both engaged in spiritual collaborations with other artists.

Agnes Jones recalls Savory’s passion for high standards, as in 1966 when he accused artists in Guyana of being “guilty of not being ruthless enough about the end product”. He told me in 1993 that he was always criticizing his work, looking back, and seeing room for improvement. He was serious about matters such as this, and the place and role of the artist. In his 2010 “Evocations” exhibition in Guyana, he included two sessions discussing these matters.

Savory’s understanding of Guyana was intrinsic to the landscape and it was original. He found something that was originally Guyanese in the hinterland landscape. His works answered a perceptive call made by the great Burrowes in 1952, for a “more sincere and satisfying” way of doing art in Guyana when Burrowes declared that Guyanese artists could no longer follow the path of naturalism. His interest in the pre-Columbian history of the Americas was also a part of this urge to find the original condition of the place.

Savory has left Guyana and the Caribbean with a rich store of artwork in the form of original paintings. He has also left a way of seeing and responding to the Caribbean landscape which no one had done before, and no one has managed to do since. He helped to build a hopeful, valuable cultural space in Guyana, which, along with political independence, was one of the great things that this country achieved in the 1960s -70s. Part of his legacy is also his passion for understanding and depicting the rootedness of the Caribbean and the true nature of its history.