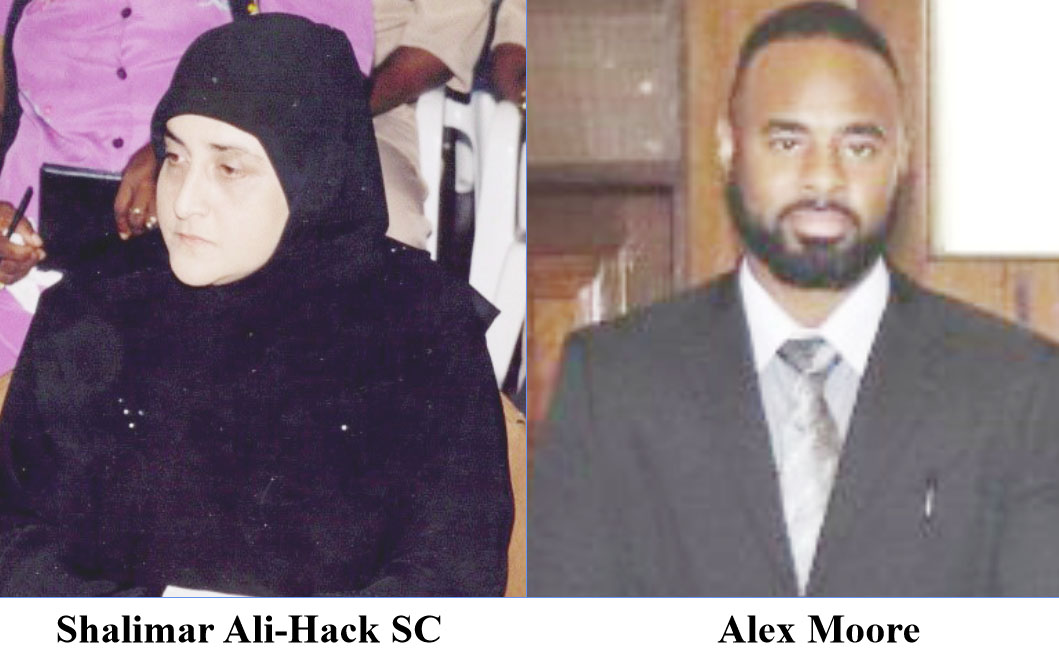

High Court judge Navindra Singh on Tuesday threw out a $50 million lawsuit filed by Magistrate Alex Moore against Director of Public Prosecutions (DPP) Shalimar Ali-Hack SC, whom he had accused of defaming him.

Dismissing the claim, Justice Singh found, among other things, that the DPP was entitled to the defence of qualified privilege as a letter she wrote, which was the basis of Moore’s complaint, had been written in her professional capacity, for which she is protected under the law.

The magistrate has now incurred a debt of $200,000, which the judge has ordered him to pay to Ali-Hack by Christmas Eve.

Moore, through his attorney Arudranauth Gossai, has signaled his intention to appeal the ruling.

In his statement of claim, dated July 22nd, 2020, Moore was seeking in excess of half a million dollars in damages for what he said was the defaming of his character by the DPP without any reasonable or probable cause.

In a correspondence of December 5th, 2019, Magistrate Moore said, the DPP “falsely and maliciously” wrote and published the defamatory content concerning him.

That letter contained the DPP’s complaint to the Chancel-lor and Chief Justice surrounding a request for Moore’s removal as the magistrate conducting the preliminary inquiry (PI) into the murder charge against Marcus Bisram.

The DPP had argued that the complaint against Moore was an official act within her competence as an officer of the State, directed to another officer of the State in regard to matters of public interest to both her and the Chancellor, and regarding matters confidential and privileged and could not, therefore, be made the subject of legal proceedings.

She had pointed out, too, that the magistrate, by the nature of his pleadings on the face of it had demonstrated what she described as a perfectly good defence for her, in that it showed that the communication was “absolutely privileged.”

Justice Singh agreed.

The judge noted in his ruling that Articles 116 and 232 of the Constitution clearly establish that the DPP is a public officer and that further, Section 14 of the Justice Protection Act (JPA) is intended to provide protection to persons in execution of a public office, to wit, public officers.

The judge said that Moore had submitted that whether Ali-Hack was performing duties as the DPP when she penned the letter was an issue of fact to be determined at a trial.

Justice Singh said that this submission, however, seemed vacuous in light of the fact that Moore in his claim clearly pleaded that Ali-Hack was the DPP and in fact never pleaded that she penned the letter in any capacity other than as DPP and never once indicated that the concerns expressed therein were her personal complaints or opinions.

The judge reasoned that as a public officer, the DPP is protected under the provisions of the JPA.

The court also found that Moore did not comply with the provisions of the JPA in instituting his claim. On this issue, Justice Singh said that in contravention of the Act, “undisputed facts clearly” showed that the claim was instituted more than seven months after Moore had become aware of the DPP’s letter and that he also did not give her notice in writing of his intention to institute the proceedings.

According to the Act, the action has to be commenced within six months after the act complained of has been committed, and it is not to be commenced until one month at least after notice in writing of the intended action has been delivered to the defendant.

Moore had pleaded that the letter was dated December 5th 2019, which he was in possession of by December 7th 2019. He did not give notice in writing of his intention to institute the claim. The claim was not instituted until July 22nd, 2020.

“There has been absolutely no compliance or attempt to comply with the provisions of the Justice Protection Act,” the judge said; while adding further that it was perspicuous that judgment must be given for the DPP upon the magistrate’s failure to comply with the provisions of the Act.

Justice Singh also found that the DPP was protected by the State Liability and Proceedings Act, and was therefore improperly named as a party in Moore’s action.

He said he found that she was acting in her official capacity when she penned the letter to the Chancellor and Chief Justice, also in their official capacities.

Referencing case law, the judge said the law recognises that in certain circumstances the public interest requires that a person should be protected from liability for a defamatory statement even though they cannot be proved to be true or defended as fair comment and one such instance is when statements are made by one officer of the state to another in the course of duty.

The judge then went on to cite Section 12 of the Summary Jurisdiction (Magistrates) Act which provides, “The Chancellor may direct that a particular magistrate shall not adjudicate on a particular cause or matter coming before him because of the magistrate’s personal interest in that cause or matter or for any other sufficient reason and shall in any case assign another magistrate to adjudicate on that cause or matter.”

The judge reasoned further that the DPP, who has conduct of all prosecutions, as a matter of public interest must be able to communicate frankly and freely with the Chancellor in order that the Chancellor can properly make an informed decision with respect to a request under Section 12.

He said that Moore’s claim raises the defence of ‘absolute privilege’ and there are no facts pleaded capable of rebutting the defence.

“The Claim shows that the letter is irrefutably ‘absolutely privileged,’ Justice Singh said.

The DPP had said that her letter intended no malice against Magistrate Moore but dealt only with her request to have him removed from conducting Bisram’s PI due to certain observations made by the prosecution.

Ali-Hack had said that her letter contained, among other things, complaints and allegation of misconduct against Moore in his professional capacity and not in his personal capacity and was therefore capable of being investigated by the Chancellor for purposes of invoking the disciplinary procedures set out in the Judicial Service Commission’s Rules.