From the inception, “Wolfwalkers” wants you to change the way you look at things. It’s an immediate preoccupation – formal and thematic – for the Cartoon Saloon production. The hand-drawn animation is in keeping with the previous work of the studio, which has earned acclaim for its three previous entries – “The Secret of Kells”, “Song of the Sea” and “The Breadwinner”. Like that trio of films, “Wolfwalkers” utilises a 2D animation style but the style of animation informs the narrative that unfolds. The first few minutes of the film teach us how to watch it, establishing something that becomes key. As we get used to the surroundings, we recognise that the animation is not just 2D but it is emphasised in a way to highlight its illusory qualities. We see where the lines meet each other, so that the images look like what they are – drawings coming to life. There is no imitation of realism here; instead the aesthetic vision explicates the unreality of what we see. It takes some adjustment at first, particularly because the lack of depth from the 2D animation seems almost fanciful. But the ostensible fanciful quality is a deft sleight-of-hand, though. The aesthetics come to inform, and then subvert the profundity of the tale. For, “Wolfwalkers” presents itself as a tale – caught somewhere between historical lesson and fantasy epic.

The time is the 1650s in Kilkenny, Ireland. This period date aligns with a significant and tumultuous time in Irish history, during the time of Cromwell’s violent occupation of the country. Dichotomies run through “Wolfwalkers”. Human and wolf. Real and imagined. Physical and psychic. And a central one, Irish and British. Our heroine, Robyn Goodfellowe, is a young girl living behind the fortressed walls in Kilkenny with her English father, a soldier in service to the Lord Protector. Outside the walls, wolves loom, posing a threat to the semblance of English dominion. Bill Goodfellowe is part of a troop instructed to clear the forest outside the walls of anything wild. The flora and fauna seem to retain an ancient magic that unsettles the Lord Protector. His sentiments are abhorrent, but his concerns are not unfounded. There is magic in that forest.

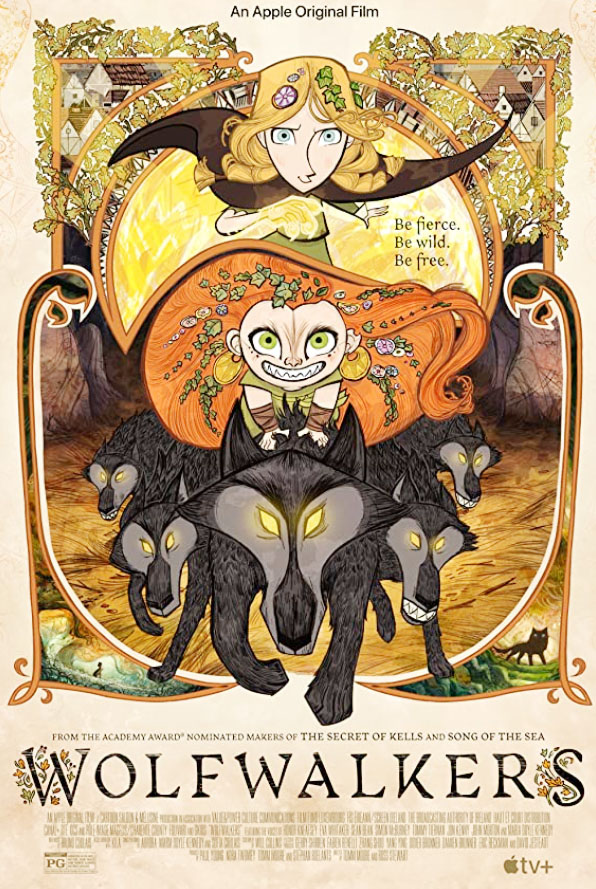

Robyn finds out as much when a headstrong attempt to prove her mettle leaves her waylaid by a pack of wolves. She is saved by Mebh, a young girl with a wild head of red hair that seems more animal than human. But, Mebh is no regular girl. She is a wolfwalker – one of a dwindling line of special guardians with the ability to shift between human and canine form. In their shape-shifting, they can retain their human form while their spirit transforms into wolves and go scavenging. Robyn is baffled but delighted by her new friend, but it’s a complicated alliance that threatens her father’s job and her relationship with him. Wolfwalkers are not part of the stoic way of life that Robyn must adhere to. And so, Will Collins’ script quickly sets up an identity crisis. Will Robyn stay true to her human responsibilities, or embrace the possibilities of the wolfwalker magic?

“Wolfwalkers” unfold with such untethered earnestness, that it catches you off guard. The story structure is uncomplicated, emphasised by the already uncomplicated animation. As directors Tomm Moore and Ross Stewart develop Robyn’s crisis of identity, the story unfolds without a hint of irony, or detachment. It’s an openness in spirit that feels almost out-of-place. But being out of place is exactly what makes “Wolfwalkers” emerges as rewarding. It is a film out of place, and of time and yet prescient and valuable. The sincerity emanating from every frame is distinctive. The December release, as the holiday season approaches in a year that’s put the world in upheaval, feels apt. The parental dynamics of Robyn and Bill are soon complemented by Mebh’s search for her missing mother. It’s a plot-point that sends the final act of the film into an aching engagement with loss and identity that raises the stakes to levels of emotional acuity that are likely to inspire tears.

There’s a seductive wistfulness to the alternate-historical roots of “Wolfwalkers”. The ways that it marries its magical realism to notions of duality and dichotomy are familiar and resonant. Robyn’s dual role as oppressed and potential oppressor, as a denizen in Kilkenny, is mined to good effect as the narrative complicates our idea of what is friend and who is foe. The fact that the animated wolves are not drawn prettily forces us to recontextualise how we respond to the things we see. As the film goes on, “Wolfwalkers” challenges us to rethink our perspectives and to give the things and people around us a second, and third look. Amidst its human interest, its metaphorical potential as an environmentalist cautionary tale is distinct

You might want to hug the children around you a little closer after “Wolfwalkers”. You might also want to have a long conversation with them about acceptance, differences, identity and the harms that humans can cause. Such are the multitudes contained in “Wolfwalkers”. It is gentle and warm and earnest in a way that feels on the brink of being too fragile, and then it also envelopes you with its intelligence and thoughtfulness emphasising the ways its attuned to the nature of people. Its modesty is its beacon, and its difference from the current slate of animated films is its boon. It will arrive to audiences just in time to deliver a welcome embrace for the season.

“Wolfwalkers” begins streaming on AppleTV on December 11.