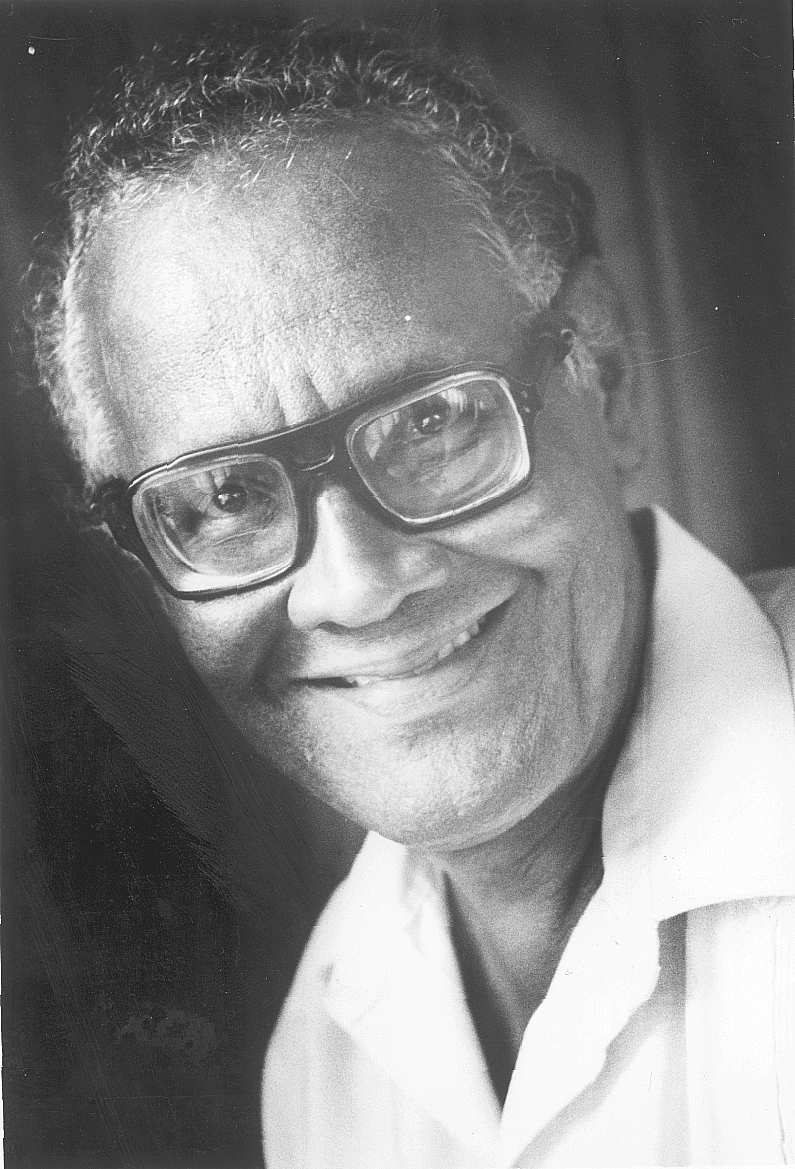

By Gemma Robinson

To mark the anniversary of Martin Carter’s passing in December 1997, Gemma Robinson looks at the ways that Carter writes about crisis.

At the start of 1955, Martin Carter predicted that this would be ‘a year of heart searchings, a year of doubt and perplexity’. Living in a state of emergency, seeking to end imperial rule, and hoping to stay true to ‘the movement of the people’, Carter wrote in Thunder that this was not just ‘a time of crisis’ but ‘a time for crisis’. In pathology, the crisis is the turning point in the development of a disease for better or worse. Carter saw 1955 as the decisive moment for his country: it could be the turning point for the liberation movement that had defined his adult life.

Rewind eighteen months and Carter had written: ‘Let not the guile of trained colonisers out-wit us. Instead let the national capitalists, the landlords, the local businessmen, the peasants unite against Imperialism under the leadership of the working class and hurl it like a vicious comoudi out of our territory.’ It was another crisis point. Carter’s heart searchings in 1953 spoke of his fears about looming divisions in a country where he believed social justice, the redistribution of power and allegiance across different groups were possible. It was a belief in a radical unity across race, gender, and class. But what Carter would learn, and as we have learnt again across the globe in 2020, is that we repeatedly live in times of, and times for crisis.

Carter saw poetry and politics as congruent, finding the consistency between their ambitions. In a short article published in 1974, he wrote:

To want to be a poet and try to be one; and to participate in politics which is what all of us do whether we realise it or not, is to try to have more life; to deepen the relations we have with each other; to explore one’s own and each other’s capacity to respond to those challenges of being and mind and spirit we issue as we exist.

Titled ‘Apart From Both’, the piece was commissioned by the newly formed Guyana Institute for Social Research and Action (GISRA). Here Carter sees politics as another way of describing social action and social organisation – something that no one can opt out of. Poetry is something to be strived for, but both poetry and politics are founded in effort: ‘to try to have more life’. And there is more: they are both linked by a focus on relationships and a curiosity to understand ourselves and each other. However, this is not fixed: the challenges of ‘being and mind and spirit’ shift as we change our ways of existence.

If Carter’s concerns seem to be moving us away from just the material world of printed poem and political party then this would fit with the aims of GISRA. Founded by the Jesuit, Father Michael Campbell-Johnston, GISRA’s work can be seen as part of larger movement in the 1970s of Liberation Theology. Twinned in its attention to struggles of faith and justice, Liberation Theology campaigned for and defended the rights of people living precariously – living in crisis – to have ‘more life’, and it is no accident that Campbell-Johnson’s memoir is titled Just Faith, A Jesuit Striving for Social Justice.

Carter’s interlinked efforts to face the challenges of his time can also help us to understand the poetry and politics that he pursued throughout his career. ‘To try to have more life’ is closely linked to other phrases about fulfilment and opportunity. ‘Is there more to life than this?’ we might ask in times of struggle. Carter’s phrase feels deliberately open, situating us firmly in the puzzle of ‘being and mind and spirit’. How should we understand our place in the world in terms of who we can be, how we can think and what we can believe?

These were not just abstract questions. It appears that Carter had not been happy in his recent role as Minister of Information and Culture and in November 1970 he resigned from his technocratic appointment. The news made the front page, The Guyana Graphic quoted him as saying that he wanted to live ‘simply as a poet, remaining with the people . . . I will not starve. I have friends . . . I have nothing more to say now. I believe in human decency. I believe in people’. Phyllis Carter’s comments were reported the next day in the Sunday Graphic article:

When Martin is happy, I am happy. If he is happy by his decision to quit the Cabinet, I am happy for that decision. After all what is important is that a man is happy in what he is doing. Martin was obviously unhappy . . . I have lived through many years of crises with my husband who is a poet. Even while he was in government, things for me were quite the same. Now it is simply a continuation of the life I have been living with him as a poet . . . Those who know of his virtue, of his contributions to the society as a poet need no enlightenment.

The ‘many years of crises’ are worn lightly here by Phyllis, and her repetition of Carter’s status as ‘a poet’ is pronounced. In a 1969 letter, C. L. R. James wrote to Carter: ‘I hope you have not entirely abandoned the writing of poetry’. He had not.

Carter had discussed a new collection with John La Rose and Sarah White, the founders of New Beacon Books, in early 1970. This collection became Poems of Succession and included a substantial new set of poems titled ‘The When Time’. Carter’s previous publication was back in 1964 – a suite of poems called Jail Me Quickly that took the pulse of the divisive energies of the period. Alissa Trotz and Arif Bulkan have argued in this newspaper that ‘As Guyanese, we have not ever found a way to comprehensively reckon with the legacy of the 1960s’. In this light, we can understand C. L. R. James’s concern. When the poems were finally published what would Carter’s poetry look like? Was ‘The When Time’ going to repeat the anger, upset and disappointments that Jail Me Quickly (1964) so eloquently and devastatingly voiced? Its final poem ends: ‘Even the round earth is tired of being round / and spinning round the sun’.

Given these final lines, what happens next in Carter’s poetry is astonishing. The zero sum game of social and racialised division, and polarised winners and losers, continues to make its mark in his work, but in his poetry we do not read about the end of the world, or the defeat of ‘being and mind and spirit’. Instead Carter’s work gives us examples of how to continue, how to begin again. Poems of Succession has been described by Rupert Roopnaraine as a collection of ‘private wonder’. It is certainly this, and in its poetic range we find a body of work that progresses out of the personal into complicated affiliations. ‘For Milton Williams’ sees Carter address the topographies of Guyana and a particular Guyanese friendship: ‘Rivers that flow up mountains are to you / what streets there are, inevitable pathways’. In ‘On the Death by Drowning of the Poet, Eric Roach’ Carter pivots between his empathy for Roach and his commitment to a life ‘that lets in the perfume of the white waxen glory / of the frangipani, and pain’.

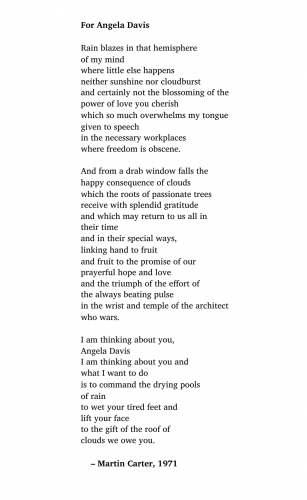

One of the most striking poems in the sequence is ‘For Angela Davis’. Dated 1971, it praises Davis’s revolutionary work, and attempts to explain her importance within the poet’s life: ‘the / power of love you cherish / which so much overwhelms my tongue / given to speech / in the necessary workplaces / where freedom is obscene’. Carter emphasises the ‘power of love’, but this is not a disavowal of the politics of race or Davis’s role in the US Black Power movement. He offers an extended metaphor about the importance of Davis’s work, weaving a vision of connected clouds, rain, trees, roots, to imagine a world:

linking hand to fruit

and fruit to the promise of our

prayerful hope and love

and the triumph of the effort of

the always beating pulse.

The metaphor of life and growth stretches in multiple directions. On one reading Davis is the ‘passionate tree’ whose watered ‘roots’ will bear fruit, love and hope. Or perhaps she is rain (‘happy consequence of clouds’) who helps to nurture the ‘passionate trees’. ‘Promise’ and ‘prayerful hope’ and the ‘triumph of the effort’ are what Davis’s ‘power of love’ produces.

Throughout the poem, rain is given a regenerative role. At the beginning ‘Rain blazes’, jolting the poetic voice to think of Davis. Rain is the generating environmental force of growth and in the final stanza it is central to a hopeful covenant:

what I want to do

is to command the drying pools of rain

to wet your tired feet and

lift your face

to the gift of the roof of

clouds we owe you.

Here the cyclical everyday aftermath of tropical rain is invested with a power to restore and connect across the Americas and beyond. And it is a connection within nature, linking the human to the land and into the supernatural. The wish to be able to ‘command’ is a wish not for power in itself, but for a power to offer comfort and solidarity from afar.

In the early 1990s, Carter appeared on BBC Radio in the UK with Fred D’Aguiar and Grace Nichols and spoke about the purpose of poetry. Discussing Nichols’s poem, ‘Blackout’, D’Aguiar said, ‘If it wasn’t for the articulacy of the writing, it would be a picture that is utterly depressing’. Nichols had written movingly that ‘Blackout is endemic to the land’. Carter replied, ‘Of course. It has to liberate her from precisely what she’s saying, so that she knows it better for having written it and therefore she has acquired some psychological distance from the raw, empirical fact. In doing so, of course, there are two gains, I think’. He went on to list the gains: ‘One is for Grace as a person, and also for people who will read it and who would come to realise that it is possible to know it and not to be defeated by it. So there is a possibility of triumph through a work of art; that art should not only be communication – the word that everybody talks about – but also a triumph of the spirit’.

But what exactly is ‘a triumph of the spirit’? Carter always leaves a lot of the work for us to do. I think ‘the triumph of the effort’ that he writes about in ‘For Angela Davis’ is closely linked to ‘a triumph of the spirit’. We might want to return to the fundamental challenges of ‘being and mind and spirit’ in ‘Apart from Both’, thinking about how we nurture the connected processes of becoming, thinking and believing in the face of an unjust world. A triumph of the spirit then is in part a belief that we can transform our conditions because we can constantly free ourselves through imagination.

Fifty years after Carter wrote his poem for her, Angela Davis spoke of her continuing anti-racist work: ‘It’s organising. It’s the work. And if people continue to do that work, and continue to organise against racism and provide new ways of thinking about how to transform our respective societies, that is what will make the difference’. Doing their work of poetry and politics, Carter and Davis encourage us to do our own. They show us how we can commit to the effort, not be defeated by what we know, and find a way to continue. And as we end another ‘year of heart searchings’ and look towards 2021 we might remember Carter’s distinction between ‘a time of crisis’ and ‘a time for crisis’ as the decisive moment. Although the risk of things getting worse always remains, Carter’s work stays open to those other turning points that can lead to better futures.

Gemma Robinson is the editor of University of Hunger: the Collected Poems and Selected Prose of Martin Carter (Bloodaxe).