Introduction

To mark the 60th anniversary of the first Tied Test match in cricket, in Brisbane on 14 December 1960, we reproduce two articles that reflect Joe Solomon’s astounding role in this historic event. With Australia on the verge of victory, he effected two crucial run outs in nine balls: both direct-hits, side-on with one stump visible. The decisive one, to dismiss Ian Meckiff, was off the penultimate ball of the match. Joe recalls the magical achievement in his usual laconic, understated and self-effacing way: ‘I was glad to be involved in such a match. I think it will be there forever’.

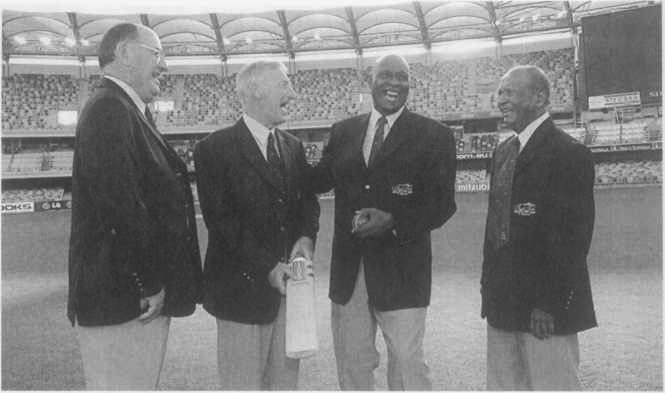

We dedicate these two pieces by Ian McDonald and Clem Seecharan to Joe Solomon who turned 90 on 24 August last. They are taken from An Abounding Joy: Essays on Sport by Ian McDonald (compiled, edited and annotated by Clem Seecharan), published by Hansib in the UK in 2019.

Cricket’s most memorable over

The Tied Test, Brisbane, 14 December 1960

By Ian McDonald

I thought we would win the second one-day International against Australia decisively, if not comfortably, so I had planned to listen from 8 o’ clock for two to three hours, then have a sleep and listen again for a couple of hours at the end. The history of our contests against Australia should have taught me better. Like thousands, perhaps tens of thousands, of others 1 ended up listening every minute all the way through to the great climax. And 1 went on listening, after GBC lost contact with Australia, to the replay of the last three balls bowled, to Dave Martins’ classic folk song, ‘We Are the Champions’, and to the people phoning in their excited views. The one I liked the best was the man who argued with what I thought was impeccable logic that since the series was 2 best out of 3 and we were the best in the 2 played so far therefore we were undoubtedly the winners. It all made up one more chapter to add to one’s unforgettable sporting recollections.

It naturally brought back memories of the Test between West Indies and Australia which built up to that famous climax in Brisbane on Wednesday, 14 December 1960. My heart always races when 1 recall that extraordinary event, undoubtedly the greatest match ever played in the greatest sport of all. That Brisbane test was a ‘purer’ tie than the tie in Melbourne in that all the available wickets on both sides fell and because of that and because it was a full five-day Test I give it pride of place – but we are privileged in one lifetime to have experienced two such games of glory.

Gamer’s last over at Melbourne will be fresh in your minds, but for my sake and yours too, can I recall again Wesley Hall’s last over in the Brisbane tie. It is more than 55 years ago but I remember the night well, sitting around a bottle of Houston’s Blue Label with four friends and pounding each other on the backs as each ball entered cricket history.

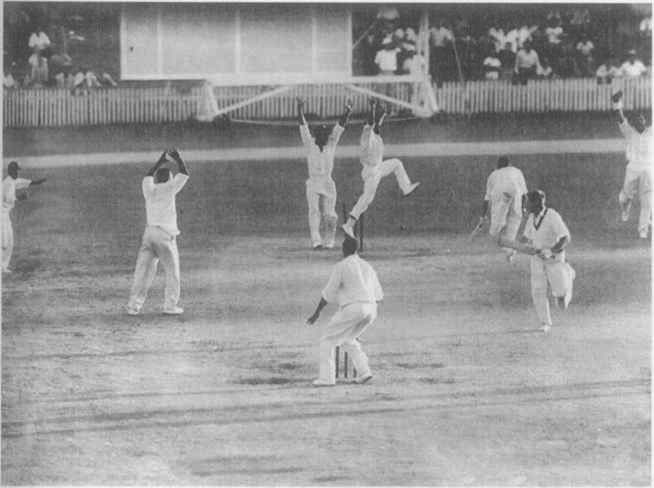

That most famous over began with Australia needing 6 to win, three wickets in hand, 8 balls to go, Hall bowling, Grout facing, Benaud at the other end. First ball of full length and good pace got up and hit Grout in the groin. Normally he would have crumpled, but Benaud was coming for the single so Grout forgot pain and ran: 5 runs to win, 7 balls to go. Hall bowled a bouncer, Benaud flashed, and Alexander screamed his appeal with all the joy in the world: 5 runs to win, 2 wickets left, 6 balls to go; Meckiff coming slowly in. Hall bowled fast and straight as a bullet, and Meckiff blocked it in a tangle of arms and legs: 5 balls left, 5 runs to win. Next ball Hall bowled fast down the leg side. Meckiff didn’t even play a shot but the batsman ran one of the strangest runs seen in Test cricket – a run while the ball went to the wicket-keeper, with Alexander hurling the ball to Hall who turned and hurled it at the bowler’s wicket but missed, and some West Indian hero threw himself full length and saved the overthrows: 4 runs to win, 2 wickets left, 4 balls to go. The next ball brought madness. Grout mishit and the ball spooned up high, high over mid-wicket. Kanhai positioned himself right under it to make the easy catch. But Hall in a frenzy of resolve charged across, jumped all over Kanhai, and dropped the catch! 1 run scored, so 3 runs were needed, 2 wickets to fall, 3 balls to go. Hall must have heard the good Lord saying, ‘You asked for ordinary miracles, not stupid ones!’ as he walked back in disgrace. Worrell came over and calmed him, encouraged him, and told him not to bowl a no-ball or else he could not return to Barbados. Hall came roaring in again. Meckiff swung and the ball sailed away to square-leg where there was no fieldsman – a sure boundary and the match won, except that Conrad Hunte sprinted to burst his heart and saved the ball on the boundary-edge and turned and threw; and from 90 yards away found Alexander’s gloves poised over the wicket and Grout, diving headlong for the crease, was run out going for the winning third run. The score was now tied: 2 balls to go, 1 run to win, 1 wicket to fall. Hall, fingering the gold cross on his chest as he started his run, bowled his heart out to Kline. Kline hit to leg. Twelve yards away, Joe Solomon, cool as ice in that crucible, from completely side-on to the wicket, swooped one-handed and threw as he picked up and broke the one stump visible to him. The greatest cricket match of all time was over. In the whole history of sport it is unlikely that there has been any period of ten minutes so highly charged with drama and emotion as that last over bowled by Wes Hall in the tied Test at Brisbane.

I have said many times that cricket is the greatest game of all games. This is not simply because above all other games it requires a combination of all the skills – batting, bowling, catching, throwing, running – and use of all the physical talents – quick eye, sharp reflexes, speed of foot, dexterity, strength and stamina. It is also the greatest game of all because, at its best, it contains drama as good as the finest theatre, plots as complex and intriguing as in well-written novels, and beauty of performances at times as piercing as a painting or a poem. In other words, at its best, cricket is an art as well as a game. At its best it is high drama on display, not just simple sport and the players all are heroes, with one or two villains, and not just ordinary sportsmen. It is a thing of passion and for a while a cricket ground becomes an amphitheatre for a performance fit for Gods.

Joe’s Tied Test, Brisbane 1960

By Clem Seecharan

Ian recalls his own experience of this great over, on the last day of the Tied Test, in the early hours of 14 December 1960. I was a boy of 10 and although I had to go to school that day, I had sneaked out of bed to listen to the last hour or so – what a magical hour! The difference between Ian and I was that I had to remain dead silent through it all or else my mom would have terminated proceedings abruptly at 3 or 4 in the morning. Sixty years on, the unimaginable events remain indelible, lodged in a poignant remoteness apprehended through the crackling airwaves.

I wish to add that while narrators of this phenomenal tale speak over and over of that last over, and rightly so, it seems appropriate to underline that Joe Solomon, at a very crucial stage of the match, with Australia needing only 7 runs to win and four wickets intact, had already thrown down the wicket from 25 yards out – side-on – only one stump being visible, thus running out Alan Davidson for 80. Set 233 to win, Australia were 92 for 6 and almost certain to lose the Test. But Richie Benaud (the captain) and Davidson (the left-arm fast bowler) had virtually secured victory with a partnership for the 7th wicket of 134 (the score being 226 for 6) when, miraculously, Joe ran the latter out: a direct hit, the 7th delivery of the penultimate over, and only 7 runs needed for victory, with one delivery and an over of 8 balls left. The 8th wicket (Benaud) fell at 228 (caught behind by Alexander to a ‘screaming’ Hall bouncer); the 9th at 232 (Grout run out, going for a third run – the winning run – brilliantly by Conrad Hunte from the square-leg boundary 90 yards away, with (as Wes Hall puts it): ‘a glorious low throw to Alexander Therefore lan Meckiff and Lindsay Kline had to score that winning run with two deliveries left. Joe Solomon’s second miracle, virtually a carbon copy of his run out of Davidson from just forward of square-leg, was off the 7th delivery of the last over or the penultimate ball of the match.

Johnnie Moyes (1893-1963), whose voice we heard all night during that tour of Australia in 1960-61 (in conjunction with Alan Mc Gilvray [1909-1996] and Ray Lindwall [1921-1996]), wrote a book on the tour, With the West Indies in Australia, 1960-61. I wish to quote briefly from it because it does convey Joe Solomon’s overall contribution to that great Test match – particularly the significance of his first crucial run out (that of Alan Davidson), in addition to his batting in both innings – rather than only the endlessly rehashed decisive run out of lan Meckiff:

[Benaud and Davidson]…ran quick singles whenever there was a chance and. now and again, when there seemed to be none. Occasionally there was a little confusion but they escaped the penalty until they had added 134 runs in about even time and the game seemed certain to end in an Australian victory. Then Benaud called for a very risky one and little Solomon hit the stumps from sideways-on before Davidson could get home, and he departed shaking his head sorrowfully…

Davidson had made 80 runs by superb batting. In those hours of tribulation he had been a sort of spinal column, rigid and strong, holding the side together [it was 92 for 6 when he joined Benaud], careful yet always ready with a calculated attack; intelligent, never completely held in bondage either by the accuracy of the bowling or by the state of the game, but moving on always towards a victory, trying desperately to lead his team out of the wilderness into the promised land…

Joe Solomon played a magnificent match for in both innings his batting rested on a solid basis in that he knew his limits and did not try to go pass them. Solomon acquir-ed his runs without fuss – 112 of them [hit wicket b Simpson 65; lbw b Simpson 47] – and twice threw down the wicket to get rid of batsmen at a crucial stage of the game. He can look back on the match with tremendous satisfaction.

That magnificent image by Ron Lovitt of the Melbourne Age, captures Joe’s left elbow extended, facilitating balance while he executes the throw; the right elbow and hand also are still fused as he propels the ball with precision onto the one visible stump – the bails are already dislodged; and the ball resting behind the stumps is clearly visible. Meanwhile, Rohan Kanhai is seen leaping into the air, higher than the stumps, apparently mistakenly celebratory of a West Indies victory.

Jack Fingleton (1908-81), former Australian batsman and cricket writer, saw the whole match and wrote a book, The Greatest Test of All (1961). This is how he describes Kline’s stroke off the penultimate ball of the match and Joe’s run out of Ian Meckiff:

And now two balls to go and one run to win…Kline got Hall’s first ball to him away to leg and both batsmen charged off. From twelve yards away, completely side-on so that only one stump showed to him, Joe Solomon swooped one-handed and threw as he picked up and the one stump visible to him went over! Up went the umpire’s finger [Umpire Colin Hoy [1922-1999]).

This was the miracle superb. Solomon couldn’t pause to take aim. Had he taken his eye off the ball coming to him, he would have misfielded – and, fielding, he had to throw at the stump by instinct. Haste was the essence of his movement. Nobody was quite there to take the throw. Had somebody been there, the delay in taking it and putting it on the stumps might have enabled Meckiff to get home. The throw had to hit the stump. Had it missed, Australia had got the winning run.

And so it ended a tie, one ball left to bowl after 3,142 balls had been bowled and 1,474 runs scored [737 by each side].

Joe, however, states that he did take aim (the image corroborates that), and he has explained to an English journalist (Frank Keating, in December 2010) the foundation of those two run outs. He takes us back to Plantation Port Mourant and the rustic means of honing the magnificent skill: ‘The secret was balance, to be perfectly steady as I took aim. You see, I was an East Indian country boy from Berbice. Out there, before we could walk, we would be pitching marbles. Later, we used to steal ripe mangoes by downing them with little sharp flat stones, not aiming at the fruit, of course, but at their stalks ’.

Yet, even with Joe’s aptitude for returning the ball with amazing accuracy and his astounding coolness under pressure, the Tied Test could easily not have happened. Peter Lashley, the left-handed Barbadian batsman who batted just after Joe in this match, at no 7, elaborates:

I was fielding close to Joe Solomon. I was at square-leg and he was at mid-wicket [forward of square]. It [the ball played by lefthander Kline] was coming to my right hand, which was my throwing hand, and his left hand, which was not his throwing hand. I was the likely person to pick the ball up, but he’d just knocked down the stumps to run out Davidson [side-on as well]; and he said: ‘Move! Move! Move! So I stopped, which was unusual for me. He swooped and picked the ball up and hit the stumps again. Had I picked the ball up, then there would have been no Tied Test.

That the ball was to Joe’s left yet he still managed to pick it up and hurl it in one motion with such precision testifies to his agility, balance and calmness amidst unimaginable tension. Joe remains an imperturbable man of impeccably good manners: no histrionics; no triumphalism; no self- importance whatsoever. `I still thank God for those two throws’, is how he recalls the historic end to that Test at the Gabba.

I met Peter Lashley in Barbados in 2011 and we spoke about the Tied Test in Brisbane. He was a young man of 23 at the time, inclined to impetuosity, so he would normally have acted on impulse and gone for that ball because he was younger than Joe Solomon (aged 30). He does not know why he deferred to Joe, possibly because Joe was so vocally decisive that it was his ball – he was definitely going for it. But Lashley is emphatic that if he had got to the ball first (as he probably would have), he does not believe he had the nerve to throw down that one visible wicket. Joe did it twice in nine balls. Joe was, indeed, the man for the occasion – the historic moment! As Wes Hall recalls: ‘Solomon swooped on the ball like an eagle and with only one stump to aim at skittled the wickets What he does not say, as Lashley points out, is that the ball was on Joe s left, so he had to retrieve it from his ‘wrong’ side with his right hand (his throwing hand) while maintaining balance, as he aimed and threw instantaneously at one stump – all in a matter of seconds!

Wally Grout (1927-1968), the Australian wicket-keeper, believed that anyone but Joe Solomon would have missed the only stump visible in that final throw: ‘Solomon? He’d always been the quiet one, never getting excited like the rest. Right then, it seemed all over [as Kline played Hall to forward square-leg and he and Meckiff set off for the winning run]. We were going to come out on top in this fantastic finish. Then Joe Solomon took careful and deliberate aim at the wicket Meckiff was approaching. The ball hit the stumps side-on. Meckiff was out…Solomon, the quiet one, had taken his time at that vital moment. Anyone else in the same position and situation would have flung the ball wildly at the wicket with nothing but hope to guide it ’. Garry Sobers, like Peter Lashley, had prayed that the ball would not come his way. Sobers recalls: ‘Joe calmly hit that wicket side-on – a target less than a couple of inches across. An inch out with his throw and we would have lost the match’.

Alan McGilvray, who was commentating on the match, had left the Gabba ground two hours before its conclusion (to his eternal regret) in order to catch a plane to Sydney. But he would discuss the proceedings with just about every cricketer who was absorbed by the historic events. This is his final assessment, taken from his book, The Game is not the Same…[1985]. He makes a point which I have seen nowhere else, that Frank Worrell had ‘raced’ to the wicket at the bowler’s end because he wished Solomon to return the ball to him, as Lindsay Kline was running to the danger end. Joe, of course, did it his own way. He needed a direct hit:

Frank Worrell… raced to the bowler’s end and called for the ball.

It was a certain run out at that end since Kline had been late in responding to Meckiff’s call. But the noise at the time was deafening. The crowd was screaming. The players were screaming. Solomon had no hope of hearing his skipper’s call. He threw to the wicket-keeper’s end. He had the width of no more than one stump to hit from his side-on position. In perhaps the most significant piece of fielding in the history of Test cricket, little Joe Solomon’s throw honed in on the stumps like a laser beam. Meckiff was still a yard short and umpire Hoy’s finger went up.

The famous Ron Lovitt image does show Worrell behind the stumps at the bowler’s end, with Kline still some way from the crease as he looks across, over his right shoulder, and glances at Joe Solomon’s throwing motion that leaves Meckiff just failing to make his ground.

Ian is right! This Tied Test in Brisbane was fit for the Gods. Joe, in his self-effacing way, said he was the beneficiary of divine intervention. But, in 2009, he spoke to Guyanese educationist, Julius Nathoo, about the magical moment. It should be noted that Joe and Julius were Christian Indo-Guyanese from Plantation Port Mourant, in the county of Berbice. John Trim, Rohan Kanhai, Basil Butcher, Joe Solomon, Ivan Madray and Alvin Kallicharran (all Test cricketers for the West Indies) were from this extraordinary plantation. It is also noteworthy that Julius Nathoo, Joe Solomon, Basil Butcher and Ivan Madray attended the Corentyne High School: education and cricket (what I have called muscular learning) were integral to the mobility aspirations of these young colonials. This is what Joe recalled for Julius:

I knew the score was tied; I knew it was the last ball of the over [it was, in fact, the second last ball of the last over of the match]; I knew that if the Australian batsmen cross over for a single, the West Indies would lose the Test match. Then Wes Hall delivered his ball and the next thing I saw was the ball coming towards me at square-leg and the batsmen crossing for a single. My adrenalin pumping, my brain stopped thinking, then everything seemed to happen in slow motion. I was about 50 yards away from the stumps. I ran forward, scooped up the ball and in one motion threw it with all my might at the one stump in view. The music of the ball hitting the stumps and dislodging the bails has never stopped ringing in my ears. All the players were on top of me and I was seeing stars.

It was the most unforgettable moment of my Test cricket career. Looking back, I made that throw in practice several times. Always I aimed right over the bails at the wicket-keeper s gloves. This time there was no time for that. Instinctively, I knew there was only one option: I had to hit the stumps. The rest was history. I am so happy that I was able to do it for the West Indies and Guyana, but specially for Port Mourant and my alma mater, Corentyne High School.

I wish to conclude this piece, ‘Joe’s Tied Test ’, with the following recollection by the Australian captain, Richie Benaud (1930-2015), of the end of that Test and its aftermath. Ian would find it both exhilarating and repellent: This excerpt is from Benaud’s book of 2005, My Spin on Cricket:

I walked out on to the field [after the tie] and Frank and I walked back to the dressing-room, arms around one another’s shoulders, and I was able to remind him that he’d said at Mascot airport [Sydney, on his arrival in Australia] in October [1960] that we’d have a lot of fun. The two teams left the dressing-rooms at 7.30 pm, having gone through most of the calypsos we all knew, the West Indians tunefully and beautifully, the Australians off key but trying hard.

Then this, by which the civilised instincts of Ian McDonald would be utterly profaned – the mean-spiritedness of small minds in authority one encounters everywhere. Benaud recalls:

There were a couple of postscripts to the joyful time after the Tied match. The so well-named Australian Board of Control, at the instigation of the Queensland Cricket Association delegates, issued an instruction that players should in future vacate dressing rooms within a few minutes of the close of play. The Board delegates enthusiastically approved the instruction. Bradman was the only one who voted against it. And, as a minor matter [for Ian, one of great magnitude] in a general clean-up of waste paper a few years later, the scorebooks of the Tied Test match were put through the shredder, or whatever was used for disposing of rubbish in those days ]emphasis added].

West Indies cricket authorities do not have a monopoly on philistinism. So the final word on the West Indies tour of Australia in 1960-61 must go to Richie Benaud reflecting on his West Indian counterpart, Sir Frank Worrell [1924-1967]:

‘Had Frank failed on that tour it would have set back West Indies cricket and especially black cricketers, by twenty years… captaining Australia against his side that series, I saw for the first time that West Indies had been moulded into a team. Frank was a good tactician with a calm exterior…He had a calm influence on excitable individuals… They did exactly what he asked of them…It was because of Frank they never collapsed when the tension mounted, as had been their wont in the past. They did much for our cricket in Australia’.