Introduction

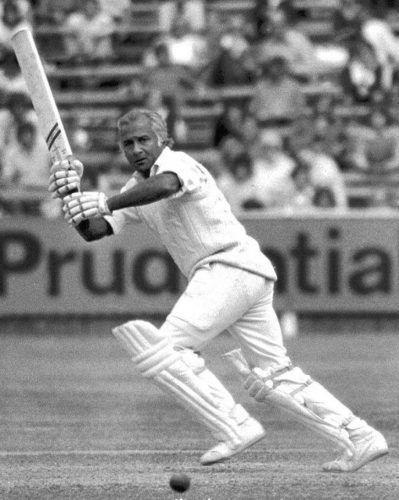

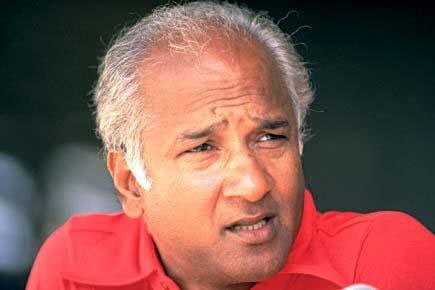

Rohan Kanhai was born on 26 December 1935 at Plantation Port Mourant, Corentyne, Berbice. He will be 85 tomorrow. To mark the occasion, we are publishing two pieces by Ian McDonald and Clem Seecharan, a tribute to the mastery of this gifted Guyana and West Indies batsman. They are taken from ‘An Abounding Joy: Essays on Sport by Ian McDonald’ (compiled, edited and annotated by Clem Seecharan), published by Hansib in the UK in 2019. Seecharan’s essay is a revised version of his response to McDonald’s piece.

In 79 Tests, between 1957 and 1974, Kanhai scored 6,227 runs at an average of 47.53, with 15 centuries; in 421 first-class matches, between 1955 and 1981, he scored 29,250 runs at an average of 49.40, with 86 centuries. (He captained the West Indies in 13 Tests, in 1973-74.) But more than the records, impressive though they are, is the dynamism of Kanhai’s batting that enchanted the cricketing world from the late 1950s to the early 1970s. Shortly after his last Test appearance, in Port-of-Spain in April 1974, Michael Gibbes, the Trinidadian journalist, wrote of Rohan: ‘His niche in West Indies cricket is assured, as is his place in the hearts of all who treasure human excellence in any form’.

Rohan Kanhai: Batsman Extraordinary

By Ian McDonald

When I was asked by Cricinfo to join the panel choosing an All-Time West Indies Cricket XI, my first inclination was to decline. I realised, in the case of batsmen alone, that it would be impossible to name all of Garry Sobers, Gordon Greenidge, Desmond Haynes, Roy Fredericks, George Headley, Frank Worrell, Clyde Walcott, Everton Weekes, Rohan Kanhai, Seymour Nurse, Clive Lloyd, Vivian Richards, Richie Richardson, Alvin Kallicharran, Brian Lara and Shiv Chanderpaul – each of whom completely deserves to be included in any West Indies All-Time Test team.

I was therefore reluctant to participate in what was bound to be a frustrating exercise. But then I decided it would be discourteous to refuse. And, in any case, I would reveal myself as too solemn a killjoy not to join in what, after all, has simply been an entertaining excursion into nostalgia.

One thing I decided was that pure statistics could not possibly be the sole, or perhaps even the main, criterion. I felt free to form a subjective impression of who our greatest champions have been through the years – partly by reading the vivid descriptions, by the great writers, of players before one’s time, and partly by experiencing oneself the art and craft and mastery of players seen live at the wicket in more recent eras. Such an impression is a matter of intuition, emotion, a seventh sense we all have that responds immediately in the presence of once-in-a-lifetime, inspired genius. We know when we have seen a really great champion, even though we may be tongue-tied in describing why we know it.

I will not reveal the list of eleven names I submitted. I wait to see the combined verdict of all ten of us on the panel. But I cannot resist revealing one name on my list simply because I fear he may not be in the final XI, given that his cold statistics may not quite convince enough of the others on the jury to put him on the list. I cannot bear to endure the sacrilege of him not being chosen in any list of the greatest West Indies batsmen.

I speak of Rohan Kanhai [1935-], of course, whom of all the sportsmen in all the many sports I have watched in my life I judge to have possessed the most compelling genius of them all.

When Kanhai came out to bat there was that sudden, expectant, almost fearful, silence that tells that you are in the presence of some extraordinary phenomenon. Of course, you could look forward to his technical brilliance. Was there ever a more perfect square drive? And has anyone in the history of the game made a thing of such great technical beauty out of a simple forward defensive stroke?

And, more than just technical accomplishment, there was the craft and art of Kanhai’s batting – no mighty hammer blows or crude destruction of a bowler, simply the sweetest exercise of the art of batting in the world.

But in, the end, I’m not even talking of these things, important though they are. There was something much more about Kanhai’s batting. It was, quite simply, a special gift from the Gods. You could feel it charge the air around him as he walked to the wicket. I do not know quite how to describe it. It was something that kept the heart beating hard with a special sort of excited fear all through a Kanhai innings, as if something marvellous or terrible or even sacred was about to happen. I have thought a lot about it. I think it is something to do with the vulnerability, the near madness, there is in all real genius. It comes from the fact that such people – the most inspired poets, composers, artists, scientists, saints, as well as the greatest sportsmen – are much more open than ordinary men and women to the mysterious current that powers the human imagination. In other words, their psyches are extraordinarily exposed to that tremendous, elemental force which nobody has yet properly defined. This gives them access to a wholly different dimension of performance. It also makes them much more vulnerable than ordinary people to extravagant temptations. The Gods challenge them to try the impossible and they cannot resist. This explains the waywardness and strange unorthodoxies that always accompany great genius.

When Kanhai was batting, every stroke he played, one felt as one feels reading the best poetry of Derek Walcott or W.B. Yeats or listening to Mozart or contemplating a painting by Turner or van Gogh or trying to follow Paul Dirac’s concept of quantum mechanics – one felt that somehow what you were experiencing was coming from ‘out there’: a gift, infinitely valuable and infinitely dangerous − a gift given to only the chosen few in all creation.

R.B. Kanhai: The Master Batsman from Plantation Port Mourant

By Clem Seecharan

…it was great education to be at the other end while Rohan Kanhai batted.

Sunil Gavaskar (1983)

Kanhai will long be remembered in Australia. When he arrived [in late 1960], he had nothing like the reputation of Sobers but, by the time he left these shores, he had firmly established himself in the hearts of all who love scintillating batsmanship.

Johnnie Moyes (1961)

And how the Gods looked out

from within this little man.

Power, Grace, Majesty in collected

divinity

…a fragment from heaven.

MacDonald Dash on Rohan Kanhai

(1963)

Ian McDonald’s first experience of young Rohan Kanhai (aged 20) was during the inter-colonial tournament of October 1956. All the matches were played at Bourda in Georgetown: Barbados v Trinidad; British Guiana v Jamaica; and the final: British Guiana v Barbados. The latter two matches were drawn, yet on the basis of their higher scores in the first innings of both, British Guiana won the tournament in 1956. It is historic that four players from Plantation Port Mourant (Berbice) appeared in these matches: Kanhai (1935-), Basil Butcher (1933-2019), Joe Solomon (1930-) and the leg-spinner, Ivan Madray (1934-2009). They were captained by Clyde Walcott (1926-2006), the great West Indies batsman who left his native Barbados in 1954 to work for the Sugar Producers’ Association (SPA) of British Guiana. His assignment was to enhance the colony’s cricket culture, already of creditable stature on sugar plantations such as Port Mourant, Skeldon, Albion and Blairmont, participants in the Davson Cup, the symbol of supremacy at cricket in Berbice, since the mid-1920s.

In the British Guiana v Jamaica match, the hosts declared on 601 for 5: Bruce Pairaudeau 111, Kanhai 129, Butcher 154 not out, Solomon 114 not out. Jamaica made 469. Off-spinner Lance Gibbs’s analysis was: 80 overs, 35 maidens, 113 runs, 4 wickets; leg-spinner Madray’s was: 84 overs, 18 maidens, 168 runs, 4 wickets.

In the British Guiana v Barbados match (the final), the four players from Plantation Port Mourant were joined by the slow left-arm orthodox/medium-pace bowler, Sonny ‘Sugar Boy’ Baijnauth (1916-85), from the adjoining plantation, Albion. The hosts made 581: Kanhai 195 (run out), Solomon 108. Barbados responded with 211: Garry Sobers 77, Everton Weekes 63. Gibbs got 4 for 68; Madray 4 for 61.

That the Berbice men, from the sugar plantations, were now clearly ascendant was primarily a consequence of the SPA’s sports organiser, Clyde Walcott. It is widely acknowledged that without his formidable authority and forthright advocacy of their merits, these rustic men could easily have remained anonymous − talented backwoodsmen – undiscovered and unsung! It was Walcott who brought the selectors in Georgetown to the well of recognition that such astounding cricketing gifts lay dormant, in a distant place beyond the capital city.

It was after Ian McDonald had witnessed Rohan Kanhai’s elegant and technically precocious play, in compiling his two centuries at Bourda in October 1956, that he wrote home to his father, in Trinidad, ecstatic that he had encountered a young batsman of genius with the skills and temperament to become a world-class player. He was not exaggerating, as Rohan’s mastery continued to blossom from the late 1950s reaching the pinnacle of his art by the mid-1960s. This was, of course, interspersed with instances of less assurance by Ian’s hero; yet he has never faltered in his appreciation of the beauty and grace of Rohan’s batting until today. As he frames it, passionately and unequivocally – with no chink in his conviction: ‘I cannot bear to endure the sacrilege of him not being chosen in any list of the greatest West Indian batsmen…Has anyone in the history of the game made a thing of such great technical beauty out of a simple forward defensive stroke? No mighty hammer blows or crude destruction of a bowler − simply the sweetest exercise of the art of batting in the world’!

When Ian saw Kanhai in 1956, he had played only three first-class matches, and he did not set Kensington Oval, Bourda or Queen’s Park Oval alight: 14, 1 (v Barbados); 51, 27 (stumped in the second innings v Australia), 23, 5 (stumped twice v Swanton’s XI) respectively. That he was stumped thrice in his first six innings is suggestive of the impetuosity of a 19-year-old not yet reined in, if such a measure were desirable or even conceivable. However, the first impressions of Rohan by the Australians, in 1955, were congruent with Ian McDonald’s initial assessment the following year. Journalist Pat Landsberg described Kanhai as ‘a dapper young Indian who showed no misgivings at the reputation of the Australians’. Ian Johnson (1917-98), the Australian captain and off-spinner, who played in the match against British Guiana at Bourda, stated succinctly: ‘…it was evident to the Aussies in that match that Kanhai’s anonymity would be short-lived’. Kanhai reflected later on his seminal encounter with the Australian fast bowler, Keith Miller (1920-2004), his innings of 51 at Bourda in April 1955: ‘…a green 19-year-old was making a fool of the cricket manuals…Miller was bowling his big outswingers and I was clouting them regularly to the square leg boundary. Nobody told me that I shouldn’t do it – that I was committing the biggest sin by hitting across the ball. This was my favourite shot and it brought me a heap of runs. Big Keith was completely flummoxed. He knew the answer to every trick in the book, but I wasn’t playing by the rules. The madder he got the more I innocently pulled him to the fence’. (This is taken from Kanhai’s book of 1966: ‘Blasting for Runs’.)

A little over a decade later, Bob Barber, the Warwickshire and England opening batsman and leg-spinner, played two Tests against the West Indies on their tour of England in 1966. One of these was at the Oval, when Kanhai made 104 in the first innings. Barber also played with Rohan in 1968 and in 1969, when they both represented Warwickshire in the English County Championship. This is his verdict: ‘Rohan was for me much the most difficult West Indian to bowl at. He was quick on his feet and almost always aggressive. A destroyer! I would say during that period (the mid-1960s) he was their (and possibly the world’s) best batsman. It was a privilege to watch him, a proud man and a wonderful player’.

Kanhai had established himself among the top three or four batsmen in the world by the early 1960s, with impressive Test averages overseas, on tours of India (67.25) and Pakistan (54.80), in 1958-59; Australia (50.30) in 1960-61; and England in 1963 (55.22). On the tour of India in 1958-59 (West Indies won 3-0), Rohan had a Test average of 67.25 and an aggregate of 538, including his highest Test score of 256 at the famous Eden Gardens, Calcutta. On the other hand, the second leg of their tour, to Pakistan in early 1959, was vastly less impressive. West Indies lost the three- Test series 2-1 for a variety of reasons: Wes Hall, though illimitable in his application, did feel keenly the loss of the synchronized menace of his ferocious fast bowling partner, Roy Gilchrist (1934-2001), sent home on the eve of their crossing the border to Pakistan (at Amritsar) because of disciplinary action. Besides, two of the three Tests (at Karachi and Dacca) were on coir matting pitches on which the peerlessly versatile Fazal Mahmood (1927-2005), the fast-medium Pakistani bowler, was unconquerable; and, finally, the Pakistani umpiring was deemed inexperienced and mediocre by several of the West Indies players. (Sobers said he was ‘umpired out three times in quick succession’.) Yet in the third Test at Lahore at the end of March 1959, on a turf pitch, West Indies retrieved the formidable form they had evinced ruthlessly in India, winning handsomely by an innings and 156 runs. Kanhai played a cultured innings of 217 in 7 hours, chanceless with 32 fours. It was witnessed by the Pakistani President, General Ayube Khan; and Rohan impressed him with the splendour of his stroke-play, as he captivated the sophisticated Lahori spectators, many being connoisseurs of the game.

Abdul Hafeez Kardar (1925-96), the Oxford-educated all-rounder and the first Test captain of Pakistan, who also led them on their first tour of the West Indies, in 1958, has left a portrait of Rohan’s brilliance in that double century at Lahore. Kardar conveys amply – and passionately − the ingenuity Rohan had already attained on his ascent to the pinnacle of his craft: ‘It was an innings that will live with us. It shall live with us as will its every stroke, each defensive forward and offensive back-foot stroke between mid-wicket and mid-on. It shall live in our memory as a reminder that in this age of cricketing prudence, indiscretions are as welcome as they are rare. Joined by Sobers [with the score on 38 for 2], Kanhai gave up the role of a backbencher and took up arms like a lord setting his lands in order [an apt analogy in Pakistan]. In a partnership of 152 runs, Kanhai’s batsmanship spoke of the thunder and told of the blood-shaking of his heart. The innings was existence itself and presence at the ground a privilege. The Kanhai-Sobers association was cheered wildly all the while by a knowledgeable crowd. We were privileged to see two princely cricketers in artistic performance. Kanhai’s was an innings to which all hearts − and the Lahore crowd always has a big heart for the visiting team − responded gaily. We shall remember for a long time his masterly innings. It shall continue to shine with increasing brilliance and shall be remembered, reviewed and recreated whenever a Test is played at the Bagh-e-Jinnah ground’.

But it was in Australia in 1960-61, against a fiercely competitive opponent, that Rohan emphatically transported himself to the Everest of international cricket. He scored more runs than any other West Indian in the Tests, as well as in the first-class matches: 503 (average of 50.30) and 1,093 (average of 64.20) respectively. Richie Benaud, the Australian captain, was magnanimous in his evaluation of Rohan’s stature as a batsman after that tour of 1960-61: ‘One of the great players to come from the West Indies since the three W’s were in full cry is Rohan Kanhai, who is a complete individualist with the bat but at the same time, when the bowler is good enough, is a highly orthodox batsman. In defence, he is very straight, and if he has a weakness it is that he sometimes chooses the wrong ball to attack − a ball that a lesser batsman would play with the greatest care. He was virtually unknown when he came to England in 1957 [aged 21]; but although much was expected of him, he was unable to live up to the talk that had preceded the team. But it was after this tour that he really began to make a name in world batting lists, and by the time he came to Australia in 1960-61 to play on a series of good batting pitches, he was reckoned to be one of the best players in the world. By the time the tour was over, there were many in Australia who listed him as the best. When West Indies came to Australia there was something of a battle between Sobers and Kanhai to decide the world’s best batsman, and it says much for Kanhai that I thought he just shaded Sobers in that series’.

J.S. Barker, the cricket writer, a Yorkshireman based in Trinidad in the 1960s, was inclined to extoll Rohan Kanhai’s style of play. He is describing a match-winning innings of 77 by Rohan (scored off 103 balls), on the fourth and concluding day of the Fifth Test at the Oval (26 August 1963), which gave Frank Worrell’s team a 3-1 victory over England. Barker’s evocative description is congruent with Ian McDonald’s discernment of his hero’s compelling precision and beauty of execution when on form. The following is from Barker’s book of 1963, ‘Summer Spectacular: The West Indies v England, 1963’, savoured by many of us in the British Guiana (B.G.) of my boyhood, in the mid-1960s.

Barker writes: ‘For Kanhai to begin his innings against a ball no longer really shining was a rare experience…He used four overs to inspect and survey the territory then swept Lock, who had taken over from Dexter, behind square with the warning shot that signalled the bombardment about to begin. It was only the fifth four of the 86 runs already on the board. Nearly three hours had been spent compiling these 86 runs. The next hour brought 70 more. Kanhai leaned easily into a half-volley from Lock and twenty youngsters at extra-cover fought for the privilege of returning it. He pulled, hooked, drove and cut with a brilliance of timing, audacity and stroke-play which had the commentators hoarsely struggling to find new epithets. Those who had the space to do so indulged in a demonstration which was a cross between gymnastics, acrobatics and a war-dance. Those who hadn’t – and that was most – waved uplifted arms like branches in a forest hit by a gale…[Kanhai] hooked Lock for an almighty six into the crowd of sore-throated West Indians under the gasometer, and he was well caught by Brian Bolus, running in from deep square-leg, trying to repeat the shot [when on 77], having swept out of sight any lingering hopes England may have had. The rest was formality only’.

West Indies were set 253 for victory. When Kanhai was dismissed the score was already 191 for 2, with only 62 needed. They won by 8 wickets: Conrad Hunte 108 not out, Basil Butcher 31 not out. Of course, West Indies chances were immeasurably enhanced by Fred Trueman (1931-2006) limping off with a painfully bruised heel, having bowled only one over in the second innings. An injection failed to restore him to a condition of utility. Barker observes: ‘This, obviously, was a tremendous blow to England. For West Indians, it tarnished the bloom of their victory, but I scarcely think Freddie [Trueman] could have reversed the result on this pitch and in such conditions’. It was a fine one for batting; and remained so on the fourth day (of five) when West Indies won. If England had won this match, the series would have ended 2-2; but they tended to depend inordinately on the gifted and accomplished Trueman throughout the series. Brian Statham (1930-2000), once persistently economical, was virtually at the end of his career; he played in two Tests and took just three wickets at 81 runs each. After Trueman their most successful bowler was the Hampshire medium-pacer, Derek Shackleton (1924-2007), recalled after nearly 12 years’ absence from Test cricket. He (like Worrell) was 39 years old when he played at the Oval in 1963; and his 15 wickets in four Tests were obtained at 34.53 each.

It was arguably the fragility of their bowling that cost England the series. But so, too, did the understated, but astute, leadership of Frank Worrell − his knack of tilting the fortunes towards the West Indies at strategic junctures. It was one-all with the emphatic victory of England (by 217 runs) in the Third Test at Edgbaston. West Indies capitulated for 91 in their second innings: Trueman 7 for 44. Worrell’s leadership was instrumental in their crucial victory at Leeds in the Fourth Test, as well as the decisive one at the Oval, which gave his team the prize, by 3-1, that memorable day towards the end of August 1963. Many still recall it as if it were yesterday.

J.S. Barker knew Frank Worrell very well, over many years. His assessment of his last tour is an inviolable accolade on his leadership: ‘…this 1963 tour, like that of 1960-61 [to Australia], was Worrell’s tour, let there be no doubt about that. Frank was the mainspring which made the magnificent machine work. He is a man of few words, on or off the field. He smiles, he frowns, he nods or shakes his head, he crooks his finger, or waves a hand and the thing is done. When he has to chide a player, it is done with a minimum of words and less fuss. His praise, equally laconic, is the most sought-after honour in the West Indies camp’.

But Worrell never did intervene, as far as I gather, to inhibit or lessen the flair, passion and spontaneity, however risky, of gifted stroke-makers like Rohan Kanhai and Garry Sobers. Similarly, with respect to the more orthodox batsman, Joe Solomon, Frank’s aim was to let him pursue his designated role unobtrusively, in his self-effacing way, with a minimum of fuss. Therefore, Rohan had the freedom to display his uniquely imaginative, falling sweep shot that took him off his feet while the ball invariably sailed over the backward-square boundary into the crowd, as he landed on his back. The great cricket writer, Neville Cardus (1888-1975), was enamoured of the shot, having witnessed Rohan’s deft execution of it several times in England, in 1963 and 1966. This is his verdict, in the latter year, on Rohan’s compelling penchant for theatre within the West Indian tradition: ‘In captain Sobers alone the West Indies can boast three brilliant exponents in one single ebullient personality: an accomplished batsman, a seam-bowler with the new ball and a googly spinner [left-arm wrist-spinner: chinaman/googly]. He is already acclaimed as the greatest all-round cricketer of the post-Grace period. But of all the delights West Indies cricket has showered on us, the galvanism of Constantine, the quiet mastery of Headley, the tripartite genius of Weekes, Worrell and Walcott, the enchanting improvisations of Ramadhin and Valentine, none has excited and delighted me, sent me so eagerly to the tip-toe of expectation as Kanhai, upright or flat on his back. He often seems to have only one object in life − to hit a cricket ball for six into the crowd at square-leg, falling on his back after the great swinging hit. The impetus of the hit, its sheer animal gusto, brings him down to earth, but it is a triumphant fall’.

Iconic, indeed! The triumphant fall!

But there was also a fundamental orthodoxy to Kanhai’s craft, rooted in command of the basics, from which his flamboyant play was derived. He could not have scaled the heights he did, for as long as he did, if he were lacking in those immemorial skills that have sustained batsmen of diverse styles over many phases in the evolution of the game. Trevor Bailey (1923-2011), the Cambridge, Essex and England all-rounder, BBC commentator and prolific cricket writer, played against Kanhai and observed him closely in his prime; he, too, knew him well. He was an unflagging admirer of Rohan; and he appreciated the finer points of his game that were the source of his mastery: ‘Rohan Kanhai is not the greatest batsman I have bowled against but few, if any, have had the power to fascinate and satisfy me more. Just as the sauce can transform a good meal into a feast, it is the stroke execution that garnishes a Kanhai innings that would make it unforgettable even when his score is not particularly large. Rohan is a…[Guyanese] of Indian extraction and like the most exciting cricketers of Asian origin there is more than a touch of Eastern magic about his batting. For, though slightly and delicately built, he has overcome this by a combination of timing, eye and the use of his wrists. He has the ability to flick, almost caress the ball to the boundary, which is especially attractive. On one occasion I fractionally overpitched a ball on his off stump. He drove at it and at the very last moment imparted an extra touch of right hand, slightly angled his bat so that it streaked between mid-wicket and mid-on before either could move’.

Bailey’s admiration for Rohan’s elegance and exuberance, conceivably because it was the very antithesis of his own style, is unconditional: ‘Rohan is essentially an extravagant and colourful performer. He is always liable to embark on strokes others would not consider, let alone attempt to execute. This flamboyant approach to batting has on many occasions brought about his downfall, but it is the reason why I find him so satisfying. When he is at his best, there is more than a touch of genius about his play which has an aesthetic appeal. He reminds me of a great athletic conjurer whose tricks sometimes fail − not because of inability, but because he attempts so much, sometimes even the impossible – he is seldom mundane. Because Rohan is one of the finest, as well as one of the most exhilarating cricketers of his generation, he has in addition to his vast range of attacking shots a basically sound defensive technique. If I could choose how I would like to be able to bat, I would select Kanhai as my model’.

John Woodcock (1926-) of the Times covered many of Rohan’s innings in England, Test and first-class for Warwickshire. He knew what he was talking about: ‘His cricket was all about self-expression, a good deal more so at times than was in the best interest of his side…No batsman ever got himself out more than Kanhai, as distinct from being got out. But in terms of pure talent, he was in Don Bradman’s class, and of much the same stamp – slight, eagle-eyed and incredibly quick-footed. When he applied himself, he was a wonderful player on every sort of pitch. No one ever played the ball later or had more strokes’. This is what Ian McDonald means when he contends that ‘pure statistics could not possibly be the sole, or perhaps even the main, criterion’ in assessing the ‘art, craft and mastery of players’.

I give the final word on Rohan Kanhai to Ian himself because he speaks for those privileged enough to have enjoyed, by whatever means, the inviolable mastery of Rohan Bholalall Kanhai, who turns 85 tomorrow: ‘All the ingredients of greatness were there, like no other batsman. And mixed into that mixture already so supremely rich there was one final ingredient – a flair and a touch that no one can define and no one can wholly grasp, but which one knew was there and felt it as the man took the field and made his walk to the wicket – something uniquely his own; a quality that made excitement grow in the air as he came in; a feeling that here was something to see that made the game of cricket more than a sport and a contest, made it also an art and an encounter with the truth and the joy that lies in all supreme human achievement’. Amen!

Postscript:

Cricinfo’s All-Time West Indies XI was announced in July 2010. Ian McDonald, in his capacity as a very fine cricket writer, was one of the 10 judges on the panel. The others were: former Test cricketer, Jimmy Adams; cricket journalists Tony Becca and Garth Wattley; cricket commentators ‘Reds’ Perreira and Fazeer Mohammed; cricket historian Hilary Beckles; sports psychologist Rudi Webster; cricket writer Frank Birbalsingh; and former West Indies media manager, Imran Khan.

The following were the nominees in the six designated categories:

Openers: Conrad Hunte, Roy Fredericks, Gordon Greenidge, Desmond Haynes, Chris Gayle.

Middle Order: George Headley, Everton Weekes, Clyde Walcott, Frank Worrell, Rohan Kanhai, Seymour Nurse, Clive Lloyd, Lawrence Rowe, Alvin Kallicharran, Viv Richards, Richie Richardson, Brian Lara, Shiv Chanderpaul.

All-rounders: Learie Constantine, Gerry Gomez, Garry Sobers, Collie Smith.

Wicket-keepers: Clyde Walcott, Jackie Hendriks, Deryck Murray, Jeff Dujon.

Fast Bowlers: Wes Hall, Charlie Griffith, Andy Roberts, Michael Holding, Colin Croft, Joel Garner, Malcolm Marshall, Courtney Walsh, Curtly Ambrose, Ian Bishop.

Spinners: Alf Valentine, Sonny Ramadhin, Lance Gibbs.

Apart from Rohan Kanhai, I have no knowledge of the other players Ian McDonald recommended for Cricinfo’s All-Time West Indies XI. But, as Ian had surmised, he did have to ‘endure the sacrilege’ of the omission of his hero.

The following were selected by the Cricinfo panel: Gordon Greenidge (Barbados), Conrad Hunte (Barbados), George Headley (Jamaica), Viv Richards (Antigua), Brian Lara (Trinidad), Garry Sobers (Barbados), Jackie Hendriks (Jamaica), Michael Holding (Jamaica), Malcolm Marshall (Barbados), Curtly Ambrose (Antigua), Lance Gibbs (Guyana).

Cricinfo had asked their readers to participate in the exercise, to make their own choice from the nominees listed above. It is noteworthy that a significant majority voted for 9 of the 11 selected by the panel of jurors. The only divergence was their choice of Desmond Haynes (not Conrad Hunte) as the other opener, while over 77% chose Jeff Dujon as the wicket-keeper (not Jackie Hendriks). I am pleased − beyond measure – that the panel selected Jackie Hendriks because ‘of his remarkable skills behind the wicket, including to spinners. And with a middle order that boasts Headley, Richards, Lara and Sobers, the XI can afford to have a pure keeper in the ranks’.

I believe that the best wicket-keeper must always be selected before ‘wicket-keepers’ who are primarily batsmen. It is an exceptionally demanding skill to master (few do); and his position is, by far, the most important one in the field. But it is invariably underestimated, as if it were merely an add-on. Wicket-keeping should be treated with the same gravity as that of a frontline bowler. Time and again, one sees difficult catches or stumpings fumbled by less than ‘pure keepers’, with fatal consequences for the fielding side. Joe Solomon told me recently that of all the West Indies wicket-keepers with whom he played (Gerry Alexander, Jackie Hendriks, Ivor Mendonca, David Allan and Deryck Murray), he considers Hendriks the most technically versatile, whatever the style of bowling or the character of the pitch with its vagaries. Bravo to the Cricinfo panelists for committing the ‘sacrilege’ of selecting a ‘pure keeper’: Jackie Hendriks, over his accomplished fellow Jamaican, batsman/wicket-keeper Jeff Dujon!