By Stanley Greaves

At National Music Festivals of the 1950s, the names that stood out in the Piano class were Ray Luck and Hugh Sam (also a composer) from Georgetown, along with Moses Telford and Joyce Laljee from New Amsterdam.

In 1968, having just arrived from Studying Art at the University of Newcastle in the UK, I was appointed Art Master at Berbice High School (BHS). Entering the threshold of the staff room, I saw someone at a desk in front leaning over to open a desk drawer. He stopped to give me a swift up and down look. I realised I had been scanned. At introductions, I learnt he was Moses Telford, the Music Teacher and recognised the name. Before going to our respective classes, I did exchange a few interesting words with him and thought here was someone to know. Later in the afternoon, I visited his home and learnt the history of the school. It was the first of many conversions involving a wide range of subjects of mutual interest. I left feeling as if I had known him for ages.

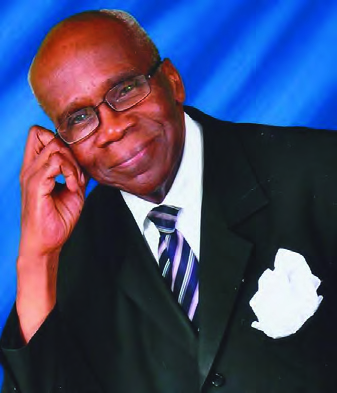

At six feet plus and always impeccably dressed, Telford was charismatic, which is not a word to be used loosely. His diction, formal with sound vocabulary, was clear and precise. He could be quite convincing and persuasive in making a point because of facts which he easily accessed. Telford was also known for not putting up with nonsense. I used to make fun of the accurate convincing clipped British accent he used in public. Our private conversations, however, were in creolese, well-peppered with local proverbs. In answer to my questioning his British upper class accent, he replied that it was easy to acquire because of his sensitivity to sounds. He said that in London shops and stores he was often served quickly because of his accent. He had an amusing tale to relate about a visit to a restaurant. After having a meal and realising that he had left his wallet at home he summoned the waiter to explain his predicament, saying that he would have to go home to return and pay the bill, which he did. I could well imagine that his gesture, the authoritative hand of the choir conductor which came naturally to him, was recognised by the waiter. I told him I would have been locked up if I had tried the same tactic.

His sensitivity to sound I could understand because it was obviously the foundation of his playing. He had begun playing the piano just before his teens and in a few years was fluently playing Mozart. He said without boasting that he was able to “coax” the sound he wanted from both piano and organ. I experienced this once when he played what I regarded as poor quality piano in the home of a mutual friend and was struck by the tonality he achieved. Telford had a large hand and long fingers which he said allowed him to really command the keyboard. But apart from this, he had a certain way of using his hands which I once told him was the hand of command. His response was affirmative and he said it was related to conducting choirs. You had to be able to command immediate attention with or without the baton. He preferred using the latter to focus attention. Watching a hand with fingers waving about could be a distraction.

The Music Room was in the new wing and after a term of ferrying a box of art materials from classroom to classroom, I “liberated” the classroom next to his at the beginning of the second term. No one complained. Our conversations over time were held during breaks and we were soon referred to as “them two brothers’. Moses’s nickname was “Mozart,” because of the times he mentioned the name of his favourite composer. Over time we discussed Philosophy, Religion, History of Theology, Literature and Music, of course. In each area he was extremely well read and conclusive in his remarks. My nickname, I learnt, was “Django”. I questioned Leach, a senior student.

“Why do you call me that? I never brought a gun to school or shot anyone.”

He was embarrassed but hiding his smile behind his hand said “Whatever you say you are going to do, you did”.

It made me realise once again that false names (of a nice kind) are an accurate and better description of who you are.

Being next door to Telford, I was able to overhear his teaching and soon became well informed about both the content and form in teaching the subject. I was enjoying free music lessons at a theoretical level. Telford was a great and knowledgeable fan of the music of the German School – Bach, Beethoven and Mozart. The latter was his forever favourite. While discussing symphonic music, I once said that I preferred quartets and he wanted to know why, seeing that the symphonic form was widely acclaimed and appreciated. My reply was dismissive as I said that the form was a lot of sturm und drang – “ a lot of noise” – as exemplified by Wagner. This was really a tongue in cheek statement. I, however, did continue to say that with quartets you were able to follow the composition closely, listening not only to the overall sound of the ensemble but also the distinct contribution of each instrument. A little while later, he said that he had never thought of quartets in that manner and had decided to pay more attention to performances. It was a humbling experience for me that he would have taken my comment so seriously.

There is a very funny incident that took place in a class overlooking a rough street on one side of the compound. A cow herder passed by each afternoon and would hang his blue portable radio on a lamppost, loudly broadcasting popular music. One day Telford took a tape recorder and directed a barrage of symphonic music at the herder. He never hung his radio again on the post. Telford despite being a disciplinarian was empathetic. He was well loved by his students while demanding excellence in everything, including academic studies, social behaviour and tidiness in dress. I used to listen to the BHS choir rehearsals, boys, girls, and mixed. One afternoon on the eve of them travelling to Georgetown to take part in a competition over the weekend, I heard him say while gesturing, “When in Georgetown you are not to behave like country bumpkins…you hear me! I want you to win three gold medals. Three medals. No less.” Which he repeated. Sitting at the back of the room, I thought: ‘One medal, certainly. Two, perhaps. But three? I also thought of problems getting girls to travel, even with chaperones present. Asked how he managed to do this, he said that he visited the homes of all participants and spoke to their parents. I could well imagine their reaction to seeing and hearing Telford. Refusals would have been out of the question. On Monday morning I eagerly went to see Telford. The choir had won three gold medals. I was stunned and asked how this could be. His response was” “Timbre (voice quality). Each choir had both African and East Indian voices, which differed, meaning that the blend of voices will be unique.” Telford explained that the critical problem faced was to create a unified tone, which he had obviously accomplished. His reasoning was quite correct.

One evening at midweek, I also attended the New Amsterdam choir practices and observed his approach to training adult voices. After practice we would visit a shop to have a drink and converse. On one occasion, when the large bottle of rum was presented, Telford immediately waved it away and asked for a proper bottle of rum. The server left without a word. I looked at Telford and he said, “Bush rum mixture.”

“How can you tell?”

“The seal was broken and repaired. I know these fellows.”

It was another sign of his strength of perception. I remembered the look I got on entering the Staff Room the first time. Drinks and conversation after choir practice became standard until he was appointed to the Teacher’s Training College where he had the reputation of a disciplinarian. This was not surprising knowing what is demanded of a real choir master. I was well aware that the principles of any discipline could be transferred to any other activity. It was a methodology both Telford and I knew was quite effective. I did apply it in School to activities other than Art.

During his stay in Georgetown before leaving to study in the US, I presented Telford with a project. Because of his admiration for Beethoven’s symphonies, I suggested that he offer to the East German Ambassador to do a lecture using LP records. It was approved and so well received that he was later presented with a complete LP collection of Beethoven’s works. Telford thanked me for making the suggestion. I had made the suggestion knowing his intellectual capability, theoretical and practical musical background would facilitate his presentation. Because I was still at BHS, I regretted not being able to attend his mid-week presentation.

Telford was brought up as a Methodist. He knew the forms of service, the hymnals and early on became a church organist. He studied at Trinity College and at the Royal College of Music he drew the attention of the renowned teacher Cyril Smith, who tutored him privately. Telford says he was badgered by two departments. One was dedicated to piano concert performances, the path that Ray Luck took, and the other was for solo voices. Telford had a resounding baritone. He, however, wanted to specialise in teaching, much to the disappointment of Cyril Smith. After graduating, he returned to Guyana to teach at the Berbice High School and later at the Teacher’s Training College. He later left for the US to do his Masters and Doctorate. He did so well that he was invited to join a well-known fraternity and was later asked to operate at a high administrative level but he declined to do so. In New York, he taught at different schools, including one for exceptional students. His reputation as a choir master and organist provided employment at churches. In one of them, he played an organ that was in need of repair and he “ had to perform magic” to get it to play. A very rich parishioner paid to have it repaired, stipulating that only Telford was allowed to play it. I asked once about the contents of his briefcase, wondering if he carried gold bricks in them. He said that among other things it contained his baton and organ-playing shoes. Further questioning revealed that any serious organist wore them in order to move freely among the foot pedals. Organists who played often apparently also walked “parrot-toed” -feet turned inwards. Telford’s preference was for older organs as opposed to the electronic variety. The tonal range was restricted.

There is the story about a church choir’s reaction when he announced that they would have to learn to sing a capella, in Latin. Loud remonstrations followed but he was adamant. After their first performances they were so delighted that they only wanted to sing in that mode. I asked the reason. Singing on vowels facilitated the production of a rich tone – as any opera lover would know. It meant the Latinate languages – Italian, Spanish and Portuguese – made this easier. Listening to spoken German I wondered how the famed baritone Fischer Deskau managed to sound so smooth.

At a particular university, his choir gained a reputation for superior performances. He wanted to take them on a tour and came up against opposition. He told the administration that the football team used a coach, so why shouldn’t this apply to the choir that brought prestige to the university. He got his wish but the head of the Music Department felt so threatened by his presence that he opposed Telford being appointed permanently. I told Telford that his bearing and manner of speaking was not in accord with how Black Americans were perceived. He was an unpredictable quantity, being in the culture and but understandably not having any intention of being of it.

In later years in the US, during a theological discussions on Agnosticism, Pantheism and Animism (to which we were both sympathetic), I remarked that with his knowledge of church history and religion, his eloquence and sharp insights he should open a US style corner church and I would welcome the opportunity to design vestments, paint religious themes, symbols, design appropriate furniture and help take up collections. His church would also be tax free. He would laugh uproariously at these suggestions whenever I made them. There is no doubt in my mind whatsoever that because of the proven quality and strengths of his abilities, he would have been quite successful in such a venture. R. Moses Telford was indeed an exemplary musician, formidable intellect, and well respected as a person. I take it as a privilege to have been considered a friend by him and would say that the quality of his character and abilities would have made the famed angelic choir gladly welcome him with open arms to enter the golden gates.