Ode to Brother Joe

Nothing can soak

Brother Joe’s tough sermon,

his head swollen

with certainties.

When he lights up a s’liff

you can’t stop him,

and the door to God, usually shut,

gives in a rainbow gust.

Then it’s time for the pipe,

which is filled with its water base

and handed to him for his blessing.

He bends over the stem,

goes into the long grace,

and the drums start

the drums start

Hail Selassie I

Jah Rastafari,

and the room fills with the power

and beauty of blackness,

a furness of optimism.

But the law thinks different.

This evening the Babylon catch

Brother Joe in his act of praise

and carry him off to the workhouse.

Who’ll save Brother Joe? Hail

Selassie is far away

and couldn’t care less,

and the promised ship

is a million light years

from Freeport.

But the drums in the tenement house

are sadder than usual tonight

and the brothers suck hard

at their s’liffs and pipes:

Before the night’s over

Brother Joe has become a martyr;

But still in jail;

And only his woman

who appreciates his humanness more

will deny herself of the weed tonight

to hire a lawyer

and put up a true fight.

Meantime in the musty cell,

Joe invokes, almost from habit,

the magic words:

Hail Selassie I

Jah Rastafari,

but the door is real and remains shut.

Anthony McNeill

Jamaican poet Anthony McNeill (1941 – 1996) was said to be widely recognised as one of the most original of the generation of poets following Kamau Brathwaite and Derek Walcott. After a period through the 1960s, Walcott and Brathwaite dominated West Indian poetry. But by the end of that decade, critic/poet Eddie Baugh identified four poets who had emerged as the new, rising individual and Caribbean poets, commanding their own voices and establishing themselves as leaders of the next generation.

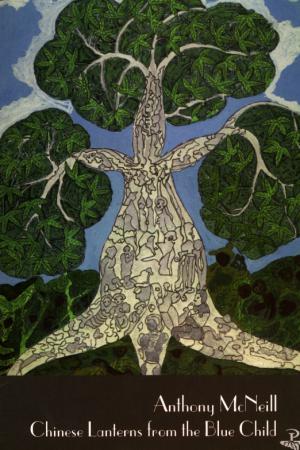

They were McNeill, Mervin Morris and Dennis Scott of Jamaica, and Wayne Brown of Trinidad and Tobago. McNeill was foremost among them. He was highly acclaimed and was the resoundingly celebrated winner of the 1995 Jamaican National Literary award for Chinese Lanterns from the Blue Child. A few of his poems were selected by critic/poet/musician/fiction writer Kwame Dawes when he edited Wheel and Come Again: An Anthology of Reggae Poetry (Peepal Tree 1998). Dawes pointed out that McNeill, “was among the first Caribbean poets to explore images of reggae and Rastafarianism in his work.” So were both Morris in such immortal poems as “Valley Prince” and “Rasta Reggae”, and Scott, with equally eternal lines in “Dreadwalk” and “Apocalypse Dub.”

McNeill is outstanding for his most prominent collections Hello Ungod (1971) and Reel from the Life Movie (1972) which demonstrate his individual talent and willingness to take risks with modernist type explorations in both form and boldness of utterance and subject, exemplified by the poems “Who’s Sammy” and “Hello Ungod”. But among his remarkable preoccupations are poems which Dawes believed express “such a thing as a reggae aesthetic.”

This reggae aesthetic, he said, manifests itself in Dub Poetry, but also in “oral pieces along with the more conventional forms.” Dawes argued, “this aesthetic has come to shape the writing of all kinds of poets from all over the world.” These are represented by the selections in Wheel. In that anthology are four McNeill poems – “Saint Ras”, “For the D”, “Bob Marley” and “Ode to Brother Joe” – that relate to this aesthetic in exploration of subject matter but go deeper in analysing the cosmos of the Rasta man. This is closely related to the music in which this consciousness is steeped, the feel of the Rasta drum, and the spiritual associations that are frequently found in the music. In fact, much of the music is created by that dynamic.

The most profound nature of these relationships may be found in the poem “For The D” – a tribute to Don Drummond, whose tragic, but poetic theme resides in the music as well as in the poet’s metaphors in a way that they cannot be separated. McNeill heard in the music an expression of the cosmos, the environment and the way the reggae musician expressed that in his music. The poet wished he could do that in poetry – express the profundity of feeling and the experience of suffering. He asked Drummond, “may I learn the shape of that hurt//which captured you nightly into//dread city, discovering through//streets steep with the sufferer’s beat.” That line, “the shape of that hurt”, is among the best you will find anywhere in poetry.

In “Ode to Brother Joe”, the poet similarly tried to capture the world, the spiritual sphere within which the Rasta man Brother Joe and his community live. In many parts of the poem, McNeill suggested that it was quite removed from reality. One is tempted to read that the Rasta’s god does not exist and his chants to Selassie are as futile as the smoke he emits. Furthermore, he has to face the law and his spiritual protestations have no power to free him.

To leave it there, however, is a limited reading of the poem from a middle-class sensibility and a standard attitude in the society that is unsympathetic if not hostile to the Rasta’s beliefs. McNeill was too complex and thorough a poet to leave it there. He expressed a tragic reality – one which is faced in contemporary society by the poor and unprivileged trying to find a way out of their plight, seeking plain physical relief and spiritual release. It shows how they come into conflict with society in so doing.

These are the things that reggae does for the working class, and part of the reason the songs of Bob Marley have such perpetual power. Reggae music responds to the need to fight for protection and liberation, and does it through not only lyrics, but also the shape of the music. McNeil’s reggae aesthetic relates to how poets and poetry connect to that music and all it stands for but is too wide ranging and complex to fully articulate here.

Dawes claimed that his published selections contain “what this anthology presumes is a reggae aesthetic – an aesthetic that one can discern in the dub poetry of Linton Kwesi Johnson and in the sonnets of Geoffrey Philip. Sometimes these poems do not look anything like a reggae song, but at their core they represent a dialogue with reggae. In some instances this dialogue is not one of celebration, but one of deep questioning, as in Anthony McNeill’s ‘Ode to Brother Joe’.”