Mikhail Tal (1936-1992), a Soviet/Latvian chess player, was an interesting man. He was a grandmaster at 21, a world champion at 23 (that record has since been broken by Garry Kasparov who won the title at 22), an attacking player par excellence and much more. Until his passing, Tal remained one of the world’s best players.

He appeared as if from nowhere, and, starting in 1957, reeled off a spectacular series of successes winning five of his six tournaments. Experts say Tal brought back romanticism to chess, with his penchant for sacrificing left, right and centre and without having regard for who or how famous was his opponent.

He overpowered the great Bobby Fischer and others comparable to Fischer on a number of occasions. Tal won the USSR national championship, unquestionably the most rigorous worldwide, and was a gold medal winner as part of the Soviet Chess Olympiad team eight times. The Chess Olympiad is held biennially.

Last week, an acquaintance and I discussed Tal and we replayed some of his games. He was unequalled in the realm of sacrifices. We examined some of his sacrifices and tried to appreciate why he did what he did. One grandmaster compared Tal to a wrestler being pinned on the mat, but then twisting to suddenly best his opponent.

Last week, an acquaintance and I discussed Tal and we replayed some of his games. He was unequalled in the realm of sacrifices. We examined some of his sacrifices and tried to appreciate why he did what he did. One grandmaster compared Tal to a wrestler being pinned on the mat, but then twisting to suddenly best his opponent.

His ingenuity was startling. Former world champion Boris Spassky said admiringly of Tal: “In our time, only when Tal appeared did chess players see that there could be a different style”. Tal’s style was daring and devil-may-care. On the board, he posed so many problems that few could solve them. Later analyses demonstrated that some of Tal’s sacrifices were unsound, but that was little consolation to those who had dropped whole points against him.

In blitz tournaments, Tal moved with amazing speed. It is perhaps psychological that a player is tempted to make fast moves in classical (long) games against a rapid player even though he himself has plenty of time on his clock. The result is a sudden, glaring blunder. A number of very strong masters blundered against Tal. Some say it was hypnotism.

Kasparov said of Tal: “His thrilling games were the favourite of every schoolboy. Tal was the ultimate ‘time player’. When his attacking genius was in full flight, his pieces seemed to move not just better but somehow faster than his opponent’s”.

Based on the games which I replayed, I believe that one of Tal’s aims was to disconcert his opponents through his unlikely sacrifices. Though they might have been unsound, his opponents were forced to solve those problems as their clocks ticked away.

Undoubtedly, Tal was a devastating contender. He handed Fischer four defeats in the Candidates Tournament of 1959 where a double round robin was played.

In today’s game, in which Tal faces Johann Hjarterson, the sacrifices are stunning.

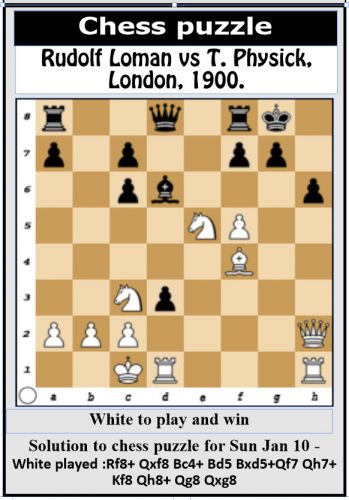

Chess game

White: Mikhail Tal

Black: Johann Hjartarson

Type of Game: Ruy Lopez, Chigorin Defence, Iceland, 1987

1. e4e5 2. Nf3Nc6 3. Bb5a6 4. Ba4Nf6 5. O-OBe7 6. Re1b5 7. Bb3O-O 8. c3d6 9. h3Na5 10. Bc2c5 11. d4Qc7 12. Nbd2Bd7 13. Nf1cxd4 14. cxd4Rac8 15. Ne3Nc6 16. d5Nb4 17. Bb1a5 18. a3Na6 19. b4g6 20. Bd2axb4 21. axb4Qb7 22. Bd3Nc7 23. Nc2Nh5 24. Be3Ra8 25. Qd2Rxa1 26. Nxa1f5 27. Bh6Ng7 28. Nb3f4 29. Na5Qb6 30. Rc1Ra8 31. Qc2Nce8 32. Qb3Bf6 33. Nc6Nh5 34. Qb2Bg7 35. Bxg7Kxg7 36. Rc5Qa6 37. Rxb5Nc7 38. Rb8Qxd3 39. Ncxe5Qd1+ 40. Kh2Ra1 41. Ng4+Kf7 42. Nh6+Ke7 43. Ng8+ 1-0.