A frenzy of sudden activity in the green and white building that Junior Emmanuel was watching, made him freeze, realising he had been spotted.

He felt like holding his head and crying again, screaming even, after waiting for ages in the heat, across the street, keenly studying the scores of veiled women completely concealed behind their heavy burqas, arriving for their normal Friday devotions. He too had prayed intently, but to recognise a familiar glide, a soft voice, a petite lithe figure, a glimpse of elegant fingers, light skin – anything really that could give him hope that his precious daughter was still alive.

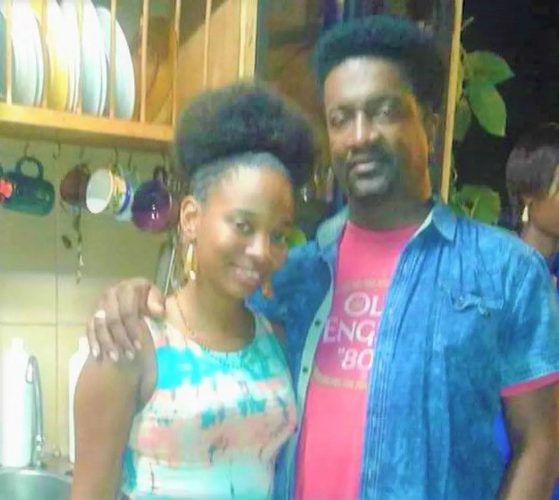

The latest anonymous caller had told him that a powerful imam in the Central Trinidad area ordered the kidnapping to make the stunning Sharday Emmanuel, 20, a fourth wife. Hiding in his vehicle outside of the mosque, two years ago, Mr Emmanuel recognised he could be in mortal danger, if the men came out armed and hostile, assuming the worst, that he was some kind of middle-aged pervert, Lord forbid.

As he sped off, asking himself for the umpteenth time, “Boy, what you doing?” the dejected father accepted that there are far too

many weirdos lurking everywhere in his homeland, including some callous souls seeking to exploit his desperation. Yet, he dares not ignore the ringing of his telephone, the endless tips, recommendations and information that lead nowhere. Mr Emmanuel keeps his daughter’s photographs, with the sweet smile, laughing hazel eyes and thick curly tresses splashed on his social media pages and those of Trinidad and Tobago’s missing people but the long list never ends, so her story slides further and further down, and away from the public’s fickle mind and interest, as the latest murderous atrocity or gruesome find takes centre stage.

He tries to get reporters to rework his lonely quest for elusive answers again, but they too want a new angle. So Mr Emmanuel loses track of the number of calls he has made to the Police, wishing for the day or night when they can finally tell him something definite but the lead investigators keep changing, and each time he has to retell his story. He doesn’t mind actually, telling his story, his daughter’s story, of how she lived, how she loved and was loved, and maybe how she died, to anyone who would listen, like I did this week.

However, the investigative files are so numerous that the case bearing the name Sharday Emmanuel is missing but he wants to believe that it is just temporarily misplaced, hidden among the others, to be found if there is but time, renewed determination and needed manpower and resources to search through the fearful stack of blood, heartbreak and tears. The Emmanuels yearn to hear from the Commissioner that the authorities have not forgotten that their only daughter went missing on June 27, 2018, while visiting her boyfriend, in a backstreet of Longdenville, in the densely populated borough of Chaguanas, about 15 miles or 24 km south-east of Port-of-Spain, the country’s capital, so their phones are always on.

A delivery driver with a local fast food chain, Mr Emmanuel and his wife Marilyn, a clerk, are simple, ordinary people, without high-level contacts or useful relatives in the protective or armed services. So the grieving parents do all they can on their own, to maintain the incessant search for what happened to Sharday, named for the successful Nigerian-born British singer Sade, their beautiful baby daughter so resembled.

They kept track of the human bones that are found all too often in bushy and remote areas here, working from their humble home that is not the same, in Mamoral Number One, a tight-knit rural community in the deep central section of the country. Following a year of endless searching along roads, ravines and rivers, Mr Emmanuel spied a news story in 2019 about a single skull and burnt remains discovered in the isolated southern forests of Santa Flora, near the old Palo Seco oilfield.

He telephoned the Police, pleaded with them to be allowed to see the find. When he went in, the female officer asked him, not in an unkind tone, “Before she even showed me the pictures, ‘You sure, you can handle this?’” In the third photograph, he recognised a mere fragment of burnt cloth, distinctly tie-dyed in beige and brown earth tones. Mr Emmanuel recalls the moment, “I just put my hand to my mouth and said, ‘Oh my God!’”

Sharday had loved colourful clothing. It was the only surviving piece of the lengthy skirt she wore on the Wednesday she disappeared. The bag of bones went to the Forensics Department for DNA testing, with a crew taking away a hair brush and other personal items from his daughter’s room for testing. Today, he is still anxiously waiting for official confirmation that would take the inquiry from a missing person report to a homicide, but he wonders whether he will have to wait another 15 years as in the ongoing case of the six-year-old child Sean Luke, allegedly murdered by two teenagers. At a recent virtual hearing, the State said it has not yet applied to admit the evidence, since the DNA analysis is outstanding, although samples were sent for testing back in 2006.

Mr Emmanuel tells of the voice notes a friend of Sharday forwarded, recounting that she wanted to break up with her partner since he was abusive. “I am going to tell my father everything that is going on,” she declared, but never got the chance. Now the father blames himself for trying to give his daughter the independence to stand on her own, while providing the support to study and become a nursing assistant, since she naturally loved animals and helping people. “I should have followed my intuition from the start,” he confesses.

“I had pleaded with him before the bones were found, say something, if you know anything at all,” adding, “I told him, ‘You know the type of girl Sharday was, she did not deserve to be lying in no drain, or in any bamboo patch, she does not deserve to be left out there, with us not knowing what happened to her.” But the young man hung his head and did not say a word. “My heart started to beat so fast, I knew. I just walked out of the room.”

Days ago, the Emmanuels travelled to the north-eastern borough of Arima, for a public vigil, joining hundreds across Trinidad praying for the safe return of kidnapped Andrea Bharrat, 23, a court clerk and graduate of the University of the West Indies. They reached out to Ms Bharrat’ relatives, jointly lit a candle for Andrea, an only child; Ashanti Riley, 18, killed last December, Sharday and all the women murdered to date, the missing and the unknown still to be found. The battered body of Andrea was retrieved the next afternoon from the desolate heights of Aripo in Sangre Grande.

Junior Emmanuel shares in fellow father, Mr Bharrat’s torment and grief. While he is heartened by people’s response to the tragedy and hopes “Something will get done, to bring us all justice, I pray all the time, it keeps me going.” He advises parents, “Keep talking to your children, and trust no one, no one, no one…”

ID understands why the Emmanuels have left the decorated Christmas tree permanently in their daughter’s room, with all her clothing intact in the cupboards. Four months ago, their son Cassiel became a father, but they missed, as always, Auntie Sharday “who would have been so excited and over-joyed.”