By Nikita Blair

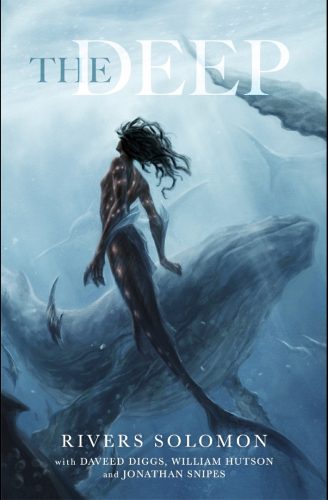

When I saw the cover of The Deep by Rivers Solomon, my mind immediately bounced back to the 2013 Animal Planet docufiction Mermaids: The Body Found. A friend of mine had told me that The Deep was more about memory and history, but still with the image of that mockumentary in my head, I somehow thought it would have been something else, a deep-sea adventure story involving mermaids and whales.

I was wrong, of course, and my friend did manage to undersell the book just enough for it to surprise me. The Deep is more than just about memory. It is a poetic rumination about the nature of memories, our individual and communal experiences with our histories and healing transgenerational trauma. Within its 150 pages, this novella managed to be so complex, that I delayed this review just so that I could have an animated book club discussion to process everything it contained.

Even the circumstances of this book’s creation turned out to be an intriguing story. Solomon, who certainly did a good job and deserves all the award nominations and wins they have garnered, did not come up with the base premise of The Deep on their own. The origins of the concept started with a 1992 techno-electro album and, over the last 27 years, the concept went through a game of telephone, as actor and musician Daveed Diggs puts it, culminating in the novella that’s available for us to read today.

So, in this review, I will try to unpack the core theme of The Deep and to explain a little bit of the fascinating history that led to its creation.

So, in this review, I will try to unpack the core theme of The Deep and to explain a little bit of the fascinating history that led to its creation.

“Our mothers were pregnant two-legs thrown overboard while crossing the ocean on slave ships. We were born breathing water as we did in the womb. We built our home on the ocean floor, unaware of the two-legged surface dwellers.” p. 28

The historical record of the Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade is written in blood, detailing the multitudes of atrocities against various peoples stolen from various African Nations. One of the more insidious of these atrocities was the fact that during the Middle Passage, pregnant women – deemed troublesome and sickly cargo – were thrown overboard to drown or be eaten by sharks.

This fact forms the base of Solomon’s novella. They take this horrific event and make an interesting speculation: what if those pregnant mothers gave birth to water-breathing babies at sea. What if these babies, free from slavery and ignorant of the horrors of their ancestry and of the ugliness of the surface world, went on to form communities and live peaceful lives in the abyssal depths of the ocean?

These people are the wajinru, the “chorus of the deep”, and the protagonist, Yetu, is one of these mermaid-like beings. Yetu is special. Unlike her fellow wajinru, whose memories fade within weeks or months, Yetu has a more intact long-term memory and her brain chemistry is more flexible than the others. As a result, when she was 14 years old, she was chosen to become the wajinru’s Historian. It’s her duty to hold the entire History of her people – every memory, sensation and emotion from all the wajinru from the past 400 years or more – so that once a year, during a three-day ritual called The Remembrance, she can return the history to the people so that they can remember who they are and where they come from.

But, there is a problem. While Yetu’s brain chemistry makes her a good Historian, she is easily overwhelmed by the weight of her people’s history. She loses herself in unsolicited Rememberings for weeks, and the process erodes her individuality and her sense of self-preservation. What makes it worse is that she’s lonely. No one around her, not even her own mother, remembers enough to understand how painful the History is to keep, and the wajinru themselves have developed a culture to be more dismissive of the past.

When the time for the Remembrance rolls around again, Yetu finds herself at a crosscurrent: should she continue to preserve the History to her detriment, or should she protect her health and individuality and leave her history behind?

“One can only go for so long without asking who am I? Where do I come from? What does all this mean? What is being? What came before me and what might come after? Without answers, there is only a hole, a hole where the history should be and that takes the shape of an endless longing. We are cavities.” – Amamba about The Rememberings, p.8

For such a slim volume, Solomon managed to pack in quite a number of themes. Most of these themes revolve around individual and communal relationships to history and memory. Yetu’s character and her role as a historian seems to pay homage to the hard and oftentimes thankless work that the world’s historians do in order to keep our histories from fading away. The wajinru’s method of history keeping – tasking a single person to keep generations worth of pure memories in their head – seems reminiscent of the fragility of oral histories and oral storytelling traditions. In a way, Solomon advocates for sharing these stories more widely, preserving them in duplicates so that should something happen, they won’t fade away for good.

More importantly, however, Yetu’s journey is about transgenerational trauma. Yetu suffers throughout much of the book under the weight of her people’s history. While she understands why she is suffering, the people around her who have long forgotten their own histories, only have vague impressions of trouble and thus cannot fully relate to Yetu’s struggle. This lack of understanding – compounded by the wajinru’s tendency to dismiss the past unless it’s time for the Remembrance – means that Yetu is a part of a community, but isn’t supported by that community. This often leads her to have mental health crises that her people do not understand and chastise her for, which compounds her suffering.

There are so many of us struggling under the weight of personal or even generational history that we don’t fully understand and which we can’t truly process because of the lack of context. On a grander scale, there are so many societal ills that confuse us because of histories unspoken or undistributed. As such, we, as a people, cannot truly heal unless we confront these problems together. I genuinely appreciate this message in Solomon’s work.

“They each held pieces of the history…They shared it and discussed it. They grieved. Sometimes they wanted to die. But then they would remember it was done.” p. 148

Healing, both on the individual and communal levels, is possible. But the journey to confront history and to heal is often painful and can be overwhelming, especially when the truth is laid bare and raw.

There are parts of the book where the perspective changes from first person singular to first person plural as Solomon immerses her readers in two Remembrances. It is through the collective voice of the ancestors and the living wajinru that we understand some of the painful history haunting Yetu.

We also get to see how she heals personally and how her community heals as well. Once everyone is on the same page after the Remembrance and once, they can all talk about it among themselves and embrace each other through the worst of the pain, the entire community is able to heal.

I think the best part about this is that once the Remembrance is over, Yetu and her mother are able to discuss the History together, and her mother even gives her insight into the history that she never thought about before. In doing so, she unlocks more potential from Yetu in the end, which leads to a brilliant finale.

The Deep has gone through three major rounds of Telephone to find itself now in book form, and might continue indefinitely, happily taking on the adaptations of each new interpreter, into the future”. – clipping. p. 156

The Deep is a brilliant novella. The story locked within its covers left me reeling as I thought about my own relationship to my personal and community histories.

But the story of how The Deep came to be is equally fascinating for lovers of music, fanfiction and trans-medium collaborative productions. Back in 1992, James Stinton and Gerald Donald created Drexciya and the trippy instrumental album series “Journey of the Deep Sea Dweller”. They, along with a few fellow musicians and illustrators created the original Drexciyan mythology. According to Daveed Diggs, they reasoned it out as such: Foetuses are alive in the aquatic environment of their mothers’ wombs. During the middle passage, pregnant African women were thrown overboard during labour. Therefore, could it be possible that they could have given birth at sea to babies that never needed air?

The project revolving around this mythos lasted for 10 years until Stinton’s death in 2002, but the concept lived on. Fifteen years later, the hip-hop band Clipping (stylised as clipping.), led by Diggs, of Hamilton and Snowpiercer fame, sampled from the Drexciya mythos to create the Hugo-nominated song The Deep. This song imagined a Drexciyan uprising against the surface world in protest of climate change and destructive deep sea seismic surveying for oil. It was interesting to hear the way they sampled from Drexciya, turning a more utopian and trippy sound into a song about environmental protection and nature’s rage.

“Y’all remember when the first blast came

And the beat fell off and the dreams got woke

And the light bent bad and the fishes belly up

And them coral castles crumbled ‘cause they wasn’t quite enough

And conversation used to break like the floor quake

Like the bleached bones and the fin friends fled from they home

But the blasts wouldn’t stop ‘cause they wanted black gold

And them no-gills had to feel it ‘cause they couldn’t be told” – excerpt of The Deep by clipping.

Finally, in 2019, Rivers Solomon published their take on the Drexciyan mythos, but based their iteration mostly on clipping.’s song. They took the song, split it in half and used it as the base for both the Rememberings and for the voices of two important wajinru ancestors: the first historian and the avenging historian who passed the role and the history onto Yetu. Solomon combined the song with her own unique prose, while also creating both the wajinru and Yetu as inlets into her imaginings of memory and history.

It was beautiful to see the progression and how each artiste and writer built on each other’s work to expand the original universe Drexciya created back in 1992.

Conclusion

The Deep is a fantastic book that takes a painful part of history, makes a utopian speculation, and then takes the result to process the relationship many people have with their personal and communal histories.

The Deep a great read for Black History Month because even though it deals with trauma, it also ends with suggestions for healing. It is also a great Republic Day/Mashramani read as it focuses on history and community, which have always been essential parts of our Republic Day celebrations.

I would like to thank Aurelius’ Raines, Elena L. Perez and Emiko of the FiyahCon Support Group Bookclub for indulging me in an animated discussion about The Deep. I could not have written this review without your additional insights into the themes explored in this book.

You can scan the QR code below to listen to The Deep by clipping. or Drexciya’s album Journey of the Deep Sea Dweller I.

Nikita Blair is a speculative fiction and creative non-fiction writer. Her work has been featured in Moray House’s Ku’wai magazine, The Guyana Annual, and the Commonwealth Writer’s blog. A collection of her work is featured on her blog, blairviews, where she writes book reviews, essays, and articles on topics of interest.

Nikita Blair is a speculative fiction and creative non-fiction writer. Her work has been featured in Moray House’s Ku’wai magazine, The Guyana Annual, and the Commonwealth Writer’s blog. A collection of her work is featured on her blog, blairviews, where she writes book reviews, essays, and articles on topics of interest.