On 4 February 2021, the Fiscal Management and Accountability (Amendment) Act 2021 was passed in the National Assembly. According to the Explanatory Memorandum, the amendments seek to correct several anomalies relating to constitutional agencies that the Assembly had approved in 2015. It defines “constitutional agency” to mean an agency listed in the Third Schedule of the Constitution. In total, there are 17 such agencies. The Schedule to the FMA Act has also been amended to include these agencies as budget agencies. The Act defines a budget agency as ‘a public entity for which one or more appropriations are made and which is named in the Schedule’.

The Minister responsible for Finance stated that the amendments streamline the budget process for constitutional agencies while at the same time preserving their independence. The 2015 amendments had set out a two-stage process whereby the budgets for these agencies were required to be sent to the Assembly in advance of the submission of the rest of the Government’s budget, after which they were incorporated to form the National Budget. According to the Minister, this practice has resulted in a fragmented and inefficient process for consideration of the National Budget; and it did not allow for the Assembly to view and consider the budget in a comprehensive manner.

In today’s article, we discuss how the budgets of constitutional agencies were dealt with prior to the 2015 amendments; the rationale for the amendments; and the reversal of these amendments via the FMA (Amendment) Act 2021.

Situation prior to 2015

Prior to 2001, all constitutional agencies were treated as budget agencies. This practice continued until 2015, despite the fact that in 2001, the Constitution was amended to provide for the financial autonomy of these agencies. Article 223A reads as follows:

In order to assure the independence of the entities listed in the Third Schedule, (a) the expenditure for each of the entities shall be financed by the direct charge on the Consolidated Fund, determined as a lump sum by way of an annual subvention approved by Assembly after it has reviewed and approved the entity’s annual budget as part of the process of determination of the national budget; (b) each entity shall manage its subvention in such a manner as it deems fit for the efficient discharge of its functions subject only to conformity with the financial practices and procedures approved by the Assembly to ensure accountability, and all revenues shall be paid into the Consolidated Fund. (Emphases added.)

Expenditures that are a direct charge on the Consolidated Fund, otherwise known as statutory expenditures, are those that are not subject to voting and approval by the National Assembly. Historically, they included the emoluments of holders of constitutional offices, repayment and servicing repayment of the public debt, and pensions and gratuities of public officers. Following the above constitutional amendment, the expenditures of constitutional agencies were to be included in the statement of statutory expenditures. This is one of the statements constituting the public accounts that is required to be audited and reported on by the Auditor General.

The words “subvention” and “subsidy” tend to be used interchangeably. They are in the nature of either a grant to a non-governmental organization, or a contribution to a government entity where, as a result of some government policy, that entity’s expenditure exceeds its revenue, thereby resulting in a deficit. Where the entity earns no revenue, its entire budget is financed by way of a subvention. Unlike statutory expenditures, subventions are approved by the Assembly via the budget process. The 2020 Estimates of Revenue and Expenditure show a listing of all subvention agencies that receive funding through their respective subject Ministries. The relevant line item that is voted for by the Assembly is 6321 – Subsidies and Contributions to Local Organisations.

Given the above, the provisions of Article 223A appear to contradict each other in that, on the one hand, the expenditures of constitutional agencies are a direct charge on the Consolidated Fund, while on the other, such expenditures are also subject to review and approval by the Assembly. Be that as it may be, during the period 2001-2015, no attempt was made to implement these important constitutional requirements, and all constitutional agencies continued to be treated as budget agencies.

FMA (Amendment) Act 2015

In order to give effect to the provisions of Article 223A, the FMA (Amendment) Act 2015 was passed. According to the Explanatory Memorandum, the purpose of the amendments was to establish the financial independence of constitutional entities by providing for lump sum payments to be made to these entities. In this way, the entities were freed ‘from the automatic obligations of Budgetary Agencies and the discretionary powers exercised by the Minister of Finance over Budgetary Agencies, which obligations compromise their independence which they are intended to have as contemplated by the Constitution’.

Budget proposals of constitutional agencies were to be submitted prior to the commencement of the fiscal year to the Clerk of the Assembly, copied to the Speaker and the Minister of Finance. The format was to be determined by the head of agency in consultation with the Minister. The Clerk was also to ensure that the proposals were submitted to the Assembly as presented, except for the Audit Office whose proposals are presented to the Assembly via the Chairperson of the Public Accounts Committee (PAC). For his part, the Minister was required to submit his comments and any recommendations, limited to the overall proposals rather than individual items, in sufficient time to enable the Assembly to consider them.

Once approved by the Assembly, the allocations of constitutional agencies were to be included as subventions to constitutional agencies and could not be altered without the prior approval of the Assembly. In addition, disbursements were to be made as a lump sum by the end of the month following the month in which the appropriation was approved. This is unlike budget agencies where disbursements are made monthly based on allotments approved by the Minister. Constitutional agencies were also required to have separate financial reporting and audit, and the related reports were to be presented to the Assembly within six months of the close of the fiscal year. The only exception was the Audit Office which submits its audited accounts to the PAC.

The implementation of the FMA (Amendment) Act 2016 took effect from 2016. In reference to the Minister of Finance’s involvement in the budgets of constitutional agencies, the Attorney General had referred to Article 122A (2) of the Constitution providing for all Courts to be administratively autonomous and to be funded by a direct charge upon the Consolidated Fund. He contended that the provisions of the FMA (Amendment) Act 2015 contravened this Article. In response, the Minister had the following to say:

… it would be foolhardy to think that any agency seeking funding from the Treasury, could just submit a budget to the Minister of Finance and expect it to be approved in the National Assembly unaltered. If that were possible, then we would not go through the painstaking exercise that attends the annual national budget.

In reality, as is the global norm, the recommended budget by any government, is circumscribed by the available fiscal space guided by the national deficit and debt sustainability targets.

What obtains now, therefore, is a more transparent system where both the request made and the proposed recommendation are shared with the National Assembly, and it is the National Assembly not the Minister of Finance which approves the final allocation to Constitutional Agencies, and has the power to vary these proposals up or down before approval.

There was also an intense debate in the Assembly in relation to a 9.6 percent reduction in the Audit Office’s budget for 2016. Suffice it to state that financial independence does not imply that constitutional agencies should be allowed to determine their budgets without reference to the considerations that are taken into account into the preparation of the national budget. In particular, the proposed overall expenditure in the national budget must of necessity take in account: (i) revenues that are expected to be garnered and collected; (ii) the extent to which there is likely to be a budget deficit; and (iii) if there is to be a deficit, the quantum of such deficit and how it is to be financed. If the cumulative expenditure proposals exceed the overall ceiling of expenditure set, then all budget agencies, including constitutional agencies, will have to revisit their proposals, with appropriate guidance from the Ministry of Finance. Of course, the national budget will have to reflect the priorities of the Government within the framework of a medium-term plan.

As reported by the Auditor General in his 2019 report, the Statement of Statutory Expenditures prepared by the Ministry of Finance did not include the expenditures of constitutional agencies. As a result, statutory expenditures were understated by $10.781 billion. Similar omissions occurred for the fiscal years 2016, 2017 and 2018 but unfortunately they did not attract any comment from the Auditor General. It would appear to be an oversight by the Ministry, and if the matter had been brought to its attention, it would not have been difficult to make the inclusion. One hopes that corrective action will be taken in respect of the 2020 public accounts due to be presented to the Auditor General by April 2021 and that the audited accounts of constitutional agencies for the years 2016 to 2020 along with the Auditor General’s detailed reports on them will be referred to the PAC for detailed examination.

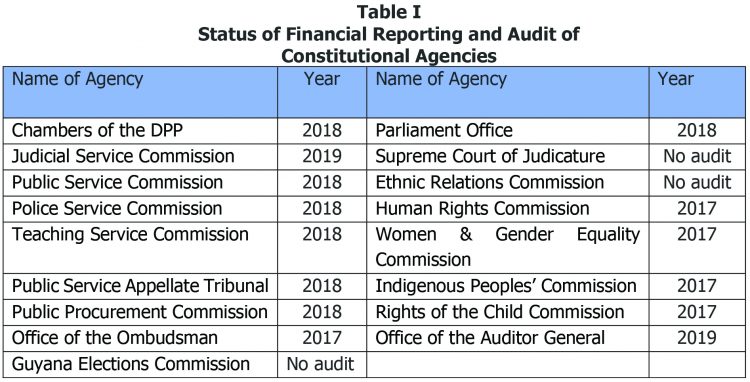

In relation to financial reporting and audit, only the Judicial Service Commission was up-to-date in terms of having audited accounts while there was no evidence that audit reports were issued for Guyana Elections Commission, Supreme Court of Judicature and the Ethnic Relations Commission. Table I gives the status of the audit of the 17 constitutional agencies:

Additionally, there was no evidence that the audited accounts were presented to the Assembly, as required.

Notwithstanding the above two shortcomings as well as the apparent contradiction in Article 223A of the Constitution, the passing of the FMA (Amendment) Act 2015 was a genuine attempt to give effect to the constitutional requirements relating to the financial independence of constitutional agencies. It is regrettable that the decision was taken to reverse the amendments via the FMA (Amendment) Act 2021.

FMA (Amendment) Act 2021

Section 80A of the 2015 amendments states that Section 80 of the Principal Act shall apply to the constitutional agencies except as otherwise provided for by the law establishing the agency. This requirement relates to annual financial reporting and audit, and the laying of the related report in the Assembly, within six months of the close of the financial year. This section has now been amended by inserting after the word “agencies” the following: ‘and the format for the annual report of a Constitutional Agency shall be determined by the official in charge of the Constitutional Agency in consultation with the concerned Minister or the Minister’.

Section 80B dealing with the procedures to be followed in the presentation of the budgets of constitutional agencies, has been amended by the deletion of sub-sections 1-4; while in respect of sub-section 5, the words ‘which shall be reviewed and approved as part of the process of the determination of the national budget’ have been inserted after the words “Constitutional Agencies”.

In accordance with Section 80C, the official in charge of a constitutional agency was responsible for preparing and presenting the annual reports and audited financial statements of the agency to the Assembly. Previously, it was the concerned Minister who was responsible for laying the report to the Assembly. This section has now been deleted.