By Renuka Anandjit and Angelique V. Nixon

Renuka N. Anandjit is a Guyanese born, Trinidad-based scholar and activist. She is a PhD Candidate, Research Assistant and Coordinator for the undergraduate student group IGDS Ignite, at the Institute for Gender and Development Studies at The University of the West Indies, St. Augustine.

Angelique V. Nixon is a Bahamas-born, Trinidad-based writer, scholar and activist. She is a lecturer at the Institute for Gender and Development Studies (IGDS) at The University of the West Indies, St. Augustine, and a director of the feminist LGBTI organisation CAISO: Sex and Gender Justice.

What do people do when they have had enough? They rise up. In Trinidad and Tobago, a nation is in turmoil, citizens and residents are outraged at the continually high levels of Gender Based Violence (GBV). On November 29th 2020, during the 16-Days of Activism Against GBV, 18-year old Ashanti Riley was kidnapped and brutally murdered. On January 29th, 22-year old Andrea Bharatt was kidnapped; her body was found on February 4th. This was the straw that broke the proverbial camel’s back. With 48 women murdered (3 were Venezuelan migrant women), 416 missing in 2020, and alarming increases in reported incidents of domestic violence and sexual abuse, a nation is saying no more to femicide and violence.

But Trinidad and Tobago is not unique. Just in the last month, in Jamaica, Andrea Lowe-Garwood was murdered during a church service, while a woman as yet to be identified was found with her throat slashed in some bushes. In Guyana, Special Constable Shonetta James was shot in the throat allegedly by her reputed husband, a police sergeant, for ending their relationship. These are not new stories, only new names. So who is responsible? Of course the perpetrators, but the causes of gender-based violence are complex and deeply implicated in colonial histories, structural violence and state failures.

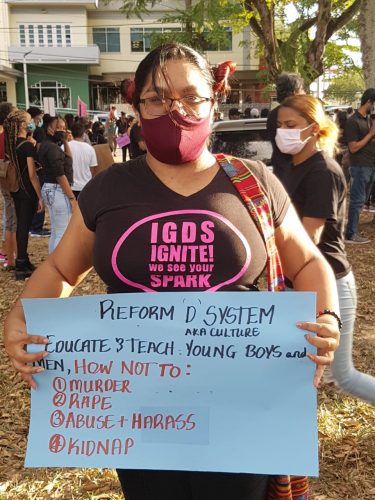

Photo taken by Renuka Anandjit

We look to Haiti, where labour unions issued a 48-hour general strike on February 1st to support protests against austerity measures, rising inflation and government corruption. Haitians have been calling for President Jovenel Moise to step down and call elections for over a year, yet the President insists he has another year left, a position supported by the United States administration. U.S. imperialism, and the turmoil it causes, is nothing new to Latin America and the Caribbean. But the people of Haiti have had enough. They are risking their lives to challenge authoritarianism and corruption once again, demanding that the government and supporters of this shameless display of power be dislodged.

But what do the labour protests in Haiti have to do with GBV and femicides across the region? To understand how violence works and affects the lives of women and girls, we have to look at the big picture. We must centre the political, legal, economic, social and cultural factors that reflect a broken system. Inadequate legislation, lack of implementation, poor policy frameworks, no interventions to address the intersecting nature of violence, corrupt and inefficient state actors. These factors shape how we navigate our lives, they govern us, they permeate our daily routines, they disenfranchise us.

Some groups or individuals have little to no power when matched against normative systems and for many, it is part of the everyday. Across the region, women’s bodies and freedoms are under attack, some subjected to these experiences due to socio-economic circumstances. In Haiti, women workers are most vulnerable and therefore taking great risk during these labour protests. Their livelihoods are threatened. Protestors have also identified kidnapping, murder, and rape as part of the daily violations. State corruption backed by economic superpowers reinforce what many of us know: some people are disposable, predominantly poor and working-class people, and many are women.

Our region is facing unprecedented economic hardships due to the COVID-19 pandemic, which has exacerbated existing inequalities within the failures of global capitalism, unsustainable development, and climate crisis. The rise in GBV globally during the pandemic has reached epidemic levels in the face of precarity. Yet regional governments have failed to prioritise this in their response, with the exception of Puerto Rico, whose Governor recently declared a state of emergency over GBV in response to demands by activists.

Since February 4th, community groups and individuals have led 100+ actions and 20+ vigils in Trinidad and Tobago to decry violence against women. The murder of Andrea Bharatt hit home for many people. But we ask why now? Why not in November when Ashanti Riley was brutally murdered in an eerily similar situation? Why not Ornella Greaves, a pregnant Black woman shot and killed on June 29th while protesting police violence in her community? Why didn’t we rise up in all the years before in such large numbers? Why are we suddenly so fed-up?

Andrea “did everything right” as many of the protests remind us. She was a bright student, a graduate of the University of the West Indies, had a job, lived with her widowed father, and was described as shy and sweet. On the day she was abducted, she was “appropriately dressed,” travelled with a friend, took an H (hire) car, instead of the unregulated PH (private hire), and was heading home right after work. Ashanti took a PH car alone, which is considered more risky. Ornella was pregnant while protesting, an action described as reckless when she should have been home. But for Andrea, an educated, young Indo-Trinidadian woman, there were no holes to poke in this narrative. She wasn’t a “bad girl,” she wasn’t from a “bad” community, she didn’t come from a “broken” home, she had no labels associated with the “wrong” kind of woman. And she was still murdered.

Surely we know that race, class and gender are intersecting factors here, but perhaps too painful to discuss while the nation is in mourning. But we can’t help but wonder, what if she was a migrant woman, a queer woman, a trans woman, or a sex worker? Would we have seen the same kind of outrage? What if the usual Carnival celebrations weren’t cancelled due to the COVID-19 restrictions? Why offer these provocations? Because it may have finally hit home for so many that no matter what women do, no matter who they are – Andrea, Ashanti, Ornella, the list goes on and on – no one is safe.

Violence overshadows every aspect of women’s lives – from failing police and court systems, lack of resources for state agencies, gaps in policy to harmful cultural norms that position women as objects and support male entitlement to women’s bodies. This analysis of institutionalized sexism and structural violence that gender justice activists have been advancing for years may have finally connected with the larger public.

Most striking in the past week is the numbers of people showing up again and again across the country. People are organising despite COVID-19 regulations. While some are using it as political opportunity, for the most part, everyday people are taking to the streets and speaking out against violence, while calling for the government to do more.

Men are finally speaking up in numbers. Perhaps it is sinking in that the “not all men” narrative is harmful and helps no one. There are numerous calls by men to hold each other accountable and promote changes in behaviours to curb violence. This builds upon years of women’s organisations and GBV actions including men in pro-feminist movement building. We have both worked in coalition with men, including the memorable #PullUpYuhBredren campaign. However, we remain wary of the ways that men may take up space and hijack social movements for their own agendas.

Young people have emerged as a force, organising and leading many of the actions. They do not want to inherit a country where women are not safe or protected. They are demanding a seat at the table and that state actors fix their country. Youth led activism has resulted in the “Write Yuh MP” campaign, led by IGDS Ignite students and born out of the need for tangible action beyond protests to amplify the voices of citizens and residents. The campaign encourages persons to make demands of their Members of Parliament and it provides letter templates, contact information and suggestions. It’s clear that youth-led activism has sparked something new and powerful across the country. Others long involved in the struggle against GBV are embracing the momentum of youth organisations.

In the past week, there has been little official response to the protests and the wide range of demands — from changes to the public transportation system to state accountability and investment in support systems and social change. Nor has there yet been a response when Civil Society Organisations started a coalition a year ago, “Alliance for State Action to End GBV”, demanding state action and investment in resources to end GBV. This year our rallying cry to the Government is to declare a National Emergency on GBV.

Some of the calls to action – from the death penalty to non-bailable sex offences charges – perpetuate state violence and are dependent upon a just legal system which we frankly don’t have. There is a long standing lack of trust in the entire justice system. The death penalty doesn’t offer any real solutions to the problems of GBV. We also question if prisons make us safe or actually deter crime. Longer sentences without a rehabilitation plan or restorative justice approach applies a bandaid on a gaping wound. While these eye for an eye approaches might feel good in the moment, they are not real solutions to the issues. These punitive approaches to crime and problems in society are rooted in state violence and colonialism.

Instead we call for investment in restorative justice and people centred transformations of our systems – from education to policing to social services. As feminist activists, we insist on a critique of state violence as we demand leadership, state action and accountability, transformation and justice to create the long-lasting change we so desperately need. We all have had enough.