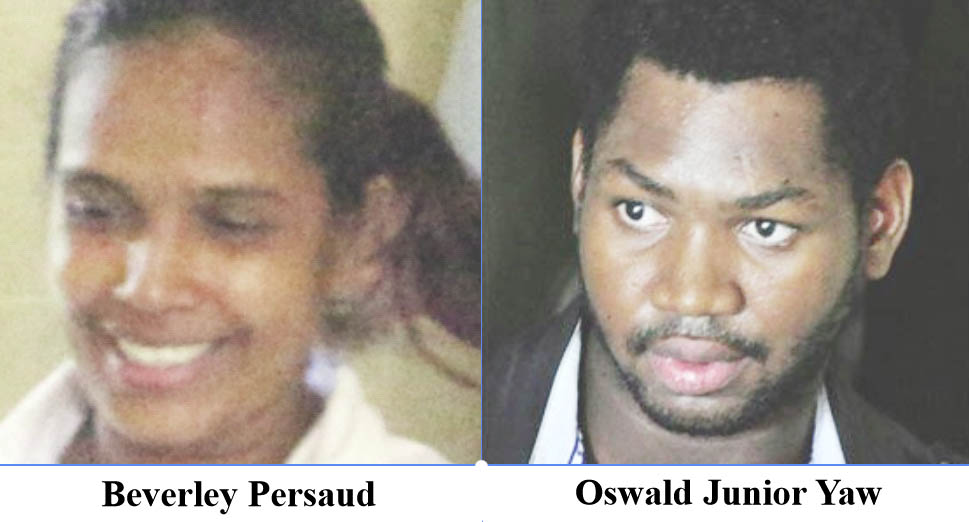

Beverley Persaud was yesterday sentenced to 29 years behind bars for the murder of her husband, while `hitman’ Oswald Junior Yaw whom she had contracted to execute the killing, was sentenced to 10 years more than her.

Late last month the two had pleaded guilty to murdering block maker Nathan Andrew Persaud who had been brutally beaten at his Herstelling, East Bank Demerara home.

The motive for the murder surrounded a property dispute between Persaud and her husband who had separated from her and moved out of the matrimonial home sometime in 2014—the year before he was killed.

Prosecutor Tiffini Lyken told the court yesterday that Persaud would later contract Yaw to kill her husband for $1.7M which, according to their agreement, she had agreed to pay in installments.

During the sentencing hearing yesterday morning, attorneys for the offenders presented stirring pleas in mitigation, advancing on their behalves how truly remorseful they were, while begging the court for mercy and to impose the minimum sentence.

For his part, Persaud’s attorney, Ravindra Mohabir, said that not only was his client sorry for what she had done, but that she craved forgiveness for her actions.

He said that she had no antecedents and had fully cooperated with the police from the inception, having revealed the part she played in her husband’s demise.

Referencing a probation report prepared on her, Mohabir asked the judge to consider that Persaud had been described by her neighbours as a peaceful person.

The lawyer, however, took issue with the said probation report which he said revealed that his client shared an abusive relationship with her husband who was responsible for her suffering a miscarriage after he had kicked her in her abdomen.

He then pointed out from the report, too, which was admitted in evidence at the sentencing hearing, an incident where the now dead man had caused his wife to sustain injuries to her head “for $40.”

Mohabir grilled Probation and Social Services Officer Sade Duncan who prepared the report; about the protocols for referring women in such circumstances, to seek professional help through a psychologist.

The lawyer sought to make the case for his client that she ought to have been referred.

Duncan contended, however, that having been requested to prepare a probation report to aid the court in the sentencing, Persaud could not at that stage of the proceedings be referred to a psychologist, even though, she (Duncan) was at that stage privy to details which would have otherwise caused her to recommend Persaud being referred for help.

Asked what prevented her from taking action to recommend such a referral, Duncan told Mohabir, “It would have had to been done before. Not at this stage.”

The lawyer suggested to Duncan that she failed tremendously in not ensuring Persaud got the assistance needed. The probation officer, however, disagreed with the lawyer.

In her own brief address to the court, Persaud said that she was sorry for what she had done and begged her husband’s family to forgive her, while expressing the hope that the man’s soul finds eternal peace.

“I am sincerely sorry, and I would like the deceased family to please forgive me. Please accept my apology,” Perasud said in a soft tone.

In her repeated calls for mercy, Persaud also sought the forgiveness of God; while adding, “may his (Persaud’s) soul rest in eternal peace.”

She then commended to Justice Navindra Singh’s consideration, what she said was her “medical condition” and her time spent on remand.

Meanwhile, in presenting her client’s plea for clemency to the court, attorney Rachel Bakker said that Yaw, too, was truly sorry for the part he had played in Persaud’s death, but in the same vein advanced that the young and impressionable man was reeled-in by an experienced Beverley Persaud who acted the role of a victim well.

Bakker said that her client regretted the loss of life for which he accepted full responsibility, but noted that on the evidence, he had taken steps to remove himself from the agreement to kill Persaud which he had told the police in a caution statement, he could not do.

Describing the death as unfortunate, Bakker presented her client as a law abiding citizen and model prisoner whom she said was a vulnerable youth preyed upon by Beverley, and because his upbringing was void of proper guidance, Beverley was able to play upon him very well, the role of a victim, causing him to believe that it was her life which had been under threat.

According to Bakker, her client is amenable to instructions and as a result would be suitable for reintegration to society. It was against this background that she requested a sentence which she said would so facilitate.

Quite different from his lawyer’s presentation, however, Yaw in his address to the court declared from the outset that he was innocent of the charge levelled against him, adding that he had so maintained even from the moment he had been arrested.

In fact, he said that the only reason he had pleaded guilty to the charge was because his lawyer had told him that given the caution statement the state had against him, he could possibly be sentenced to life in prison or worse, if convicted for the crime.

According to him, he accepted culpability, not because he was culpable, but rather it was in a bid to be able to be reunited with his five-year-old child and other relatives; while adding that had he the financial means, he would have retained a lawyer “who could fight my case.”

He claims to have confessed to a statement he signed, but not a statement which he gave to police.

Yaw did, however, acknowledge that a life had been lost for which he said he was sorry, but noted that the entire case had destroyed his reputation, even as he begged Justice Singh to give him an opportunity to prove himself worthy of returning to society.

Victim impact statements which Lyken said were prepared by the mother and niece of the deceased were read to the court.

According to the statement read in favour of his mother—Sylvie Persaud, the court heard of how she misses her son and how difficult it has been moving on in his absence, especially remembering the gruesome manner in which he met his end.

Lyken then read the victim impact statement of Angelica Persaud-Brown, who described her uncle as a father too, while reminiscing on how much he is missed at special family occasions, especially hers and his birthdays which are a day apart.

In imposing sentence, Justice Singh informed the offenders that his base for a conviction of murder is 60 years, but given that they had thrown themselves at the mercy of the court, a mandatory one-third reduction would be made for the guilty pleas.

This saw a 20-year reduction for each of them.

To the remaining 40 years in the case of Persaud, six years were further deducted for the probation report and an additional 5 years for her show of remorse; which left her with a remaining sentence of 29 years.

To Yaw’s 40 years, however, while he got a six-year reduction on account of the probation report, an additional five years were added for what the judge said was the brutality of the crime, given the injuries he inflicted on Perasud.

Yaw’s sentence thereafter amounted to 39 years.

The judge ordered that they are both to spend no less than 20 years before becoming eligible for parole.

At their initial arraignment, Persaud and Yaw pleaded not guilty to murdering the block maker.

One day later, however, they admitted that it was they who had in fact killed Persaud.

When each was asked, they had told Justice Singh that no one had forced their decision, and that they understood that by pleading to the charge they would be forfeiting their right to a trial.

The prosecution did not, however, accept pleas to the lesser offence of manslaughter, which then saw the two pleading to the capital offence on which they had originally been indicted.

Lyken had said that Persaud’s body was found at his Lot 66 Herstelling, East Bank Demerara property where he was living at the time, having previously moved out of his matrimonial home.

She said that an autopsy later revealed that he had died of haemorrhage and shock due to multiple injuries. He had been badly beaten and chopped about the body.

On the morning of September 10th, 2015 Persaud was brutally murdered at his Herstelling home. His body was later discovered after a neighbour, overhearing screams coming from the residence and later seeing a strange man leave the premises, realised something may have been amiss.