“What is this place?”

That’s the first line of dialogue spoken in Lee Isaac Chung’s “Minari” and it’s a question that reverberates through much of the film. In the opening moment, it’s spoken by Han Ye-Ri as Monica – the matriarch of the four-person nuclear family. Her husband, Jacob, has moved the family from California to a plot of land in rural Arkansas. The move does not come without issues, the first of which precipitates that opening question. As Emile Mosseri’s restless score plays, the family drives to their new home. They step out of the vehicles and contemplate the home before them: A mobile home, surrounded by vacant land that Jacob will turn into a farm. This is not what Monica expected.

In the moment, we watch Han contemplate the house before her. She raises her hands to her eye, both as a protection from the sun, but also as if to give her a moment to shutter her feelings. Her disappointment is clear, though. She raises her hands to her mouth, as if to hold back an utterance. It’s a quiet and evocative moment. And then the camera cuts away from her to a scene a few minutes later.

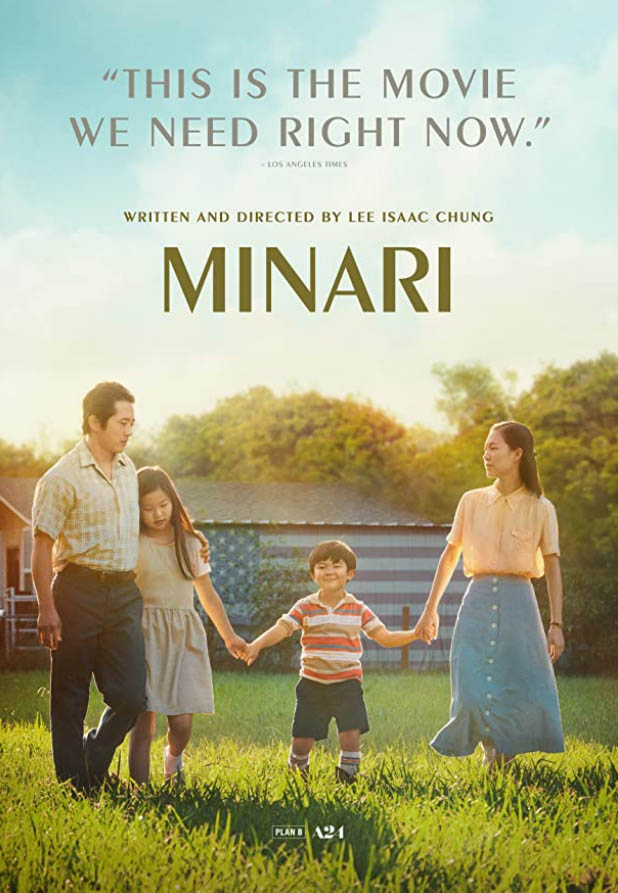

I have been thinking about that specific moment since I first saw “Minari”. The film premiered at the 2020 Sundance Film Festival to rapturous responses, winning both the U.S. Dramatic Grand Jury Prize and the U.S. Dramatic Audience Award, and in the more than a year since it’s enjoyed accolades along the way. The story of the South-Korean family making their way in the American South recalls tales of immigrants, family and childhood that are evocative. But I keep thinking about that specific cutaway, and the ways it sets us up for a tug-of-war at work in the intentions and the results of “Minari” and its investigations of family.

The film earns its title from a garden green. Early in the film, acknowledging his wife’s displacement in Arkansas, Jacob invites his mother-in-law to stay with the family. Soon-ja will take care of the children, the older girl Anne and the young boy David, while Jacob and Monica work at a nearby hatchery. To the consternation of David, Soon-ja is not a typical grandmother. She does not bake cookies, or give warm hugs. She does play cards, and tends to his wounds. And she plants. Midway through the film, she and the children plant some minari seeds by the creek nearby. The plant predicts growth and health. It’s an easy piece of symbolism: If this plant can grow amidst obstacles, surely this family can, too?

Much of the film is filtered through the perspective of David, the younger child. David is a young boy with a heart-defect that requires constant medical attention. Monica is concerned that the nearest hospitals are miles away. Jacob insists it won’t be an issue. This information arrives early in the film, but Monica’s concern never registers as particularly significant. Before the film can really investigate the parental disparity in this potential issue, Chung cuts away from the greatest discomfort. In a way this makes sense.

David seems to exist as a kind of avatar for Chung. He is not quite the main character, but the sequences in the film depend on his relationship with the initial family quartet, and then the quintet when his grandmother arrives. The family dynamics of the group offer some moments of specific tenderness. The film is mostly in South-Korean, but the parents and the children are bilingual. Soon-ja’s English is poor, though, and the language barrier creates moments of humour and warmth between her and the rest of the family. Late in the film, she comforts her ailing grandson with assurances of what happens when we die that feel too sweet to disregard. And, yet, for long stretches “Minari” feels more impersonal than incisive.

Chung favours a visual aesthetic that emphasises naturalism. It makes sense, in some ways. Jacob’s dreams of farming are rooted in an awareness and love for the pastoral that shines through. Cinematographer Lachlan Mile shoots the moments in the fields like nature documentaries, finding warmth and beauty in landscape moments that are regular but beautiful. But if the film functions as memories of David, “Minari” feels too orderly for a film that depicts the messiness of good family intentions clashing with each other. Monica asks Jacob to establish what this place is, but the 80s version of Arkansas feels too smoothly general. This story could be happening anywhere, so it feels unrooted to that specific time and place. There’s an airless comfort to the dynamics that makes for an easy watch although at times I found myself wondering, doesn’t this feel too easy?

And I return to that cut-away at the beginning from Han’s face. That avoidance of the harshest moments is, sometimes, a boon. Chung smartly avoids turning this immigrant tale into one which focuses on immigrant pain. So, we need only brief glimpses of their interaction with their white neighbours to understand the dynamics of racism at work. But there is little need to front-load suffering. Instead, in a first meeting with the all-white church, the camera ambivalently moves through the varying family members’ interaction with their neighbours. The camera stands back ambivalently, because we can intuit the implications without a need for underlining it.

It feels odd, though, that the same ambivalent tone that makes the moments of casual racism so sharp feels out of place when matched against an argument between the couple, or a later moment of stillness between a mother and her son. The aesthetic reticence might be intentional but it also seems to undercut the moments. In the gaps where the story leaves us, sometimes “Minari” feels more intent on having the audience read ourselves into the gaps than having the characters extend themselves enough to justify it. So, the cutaways, when things are just about to get challenging, feel more like avoidance than subtext. Each time the film threatens to unearth something tougher and more interrogative, Chung swerves away.

There’s a haziness to the way the moments continue, charming in a way, but too indistinct to pack an emotional wallop. It’s only when Han Ye-Ri returns to the forefront that the film feels as complex. She’s bending the film to her will in extended glances asking questions that the rest of the film seems intent on avoiding. Any ambivalence is forgotten when she arrives on screen. As the matriarch of the family, her eyes engulf the screen, creating rich complications when she interacts with any character. It’s the kind of performance that harnesses the offhand distance of the aesthetics and pulls it into sharp focus. It’s ferocious work that benefits her scene partners. Each actor becomes better opposite her. Just consider an extended conversation between her and Steven Yeun, who plays Jacob, which is one of the film’s final scenes. The two actors exchange a look of such knowing sadness that I, momentarily, found myself more moved than I anticipated. The look of sadness felt specific to these people, this place, and this time, in a way that the film needed. But then comes a final deus-ex-machina, and with a time-jump as epilogue, “Minari” swerves us away from tougher complications, yet again.

It’s not really Chung’s fault that the film has been swept up in the groundswell of the sentiment that it is “the movie that we need right now.” Yet, I find myself unable to articulate or even understand just why that calling-card is the one being used for the film. The inherent American Dream earnestness that marks the events of the family’s journey, struggling to grow like the minari plant, might be ostensibly hopeful. But it feels impossible not to read the ambivalent reality of the world into Chung’s sanguine aesthetics. That sanguinity, and emotional reticence, mean we can spot ourselves in the haziness of its family encounters. Beneath the occasional haze, it is warm and earnest and sweet. But, too often, that ostensible warmth feels like it’s hiding something hotter, angrier, and more restless beneath it.

Minari will be available on VOD release from February 26.