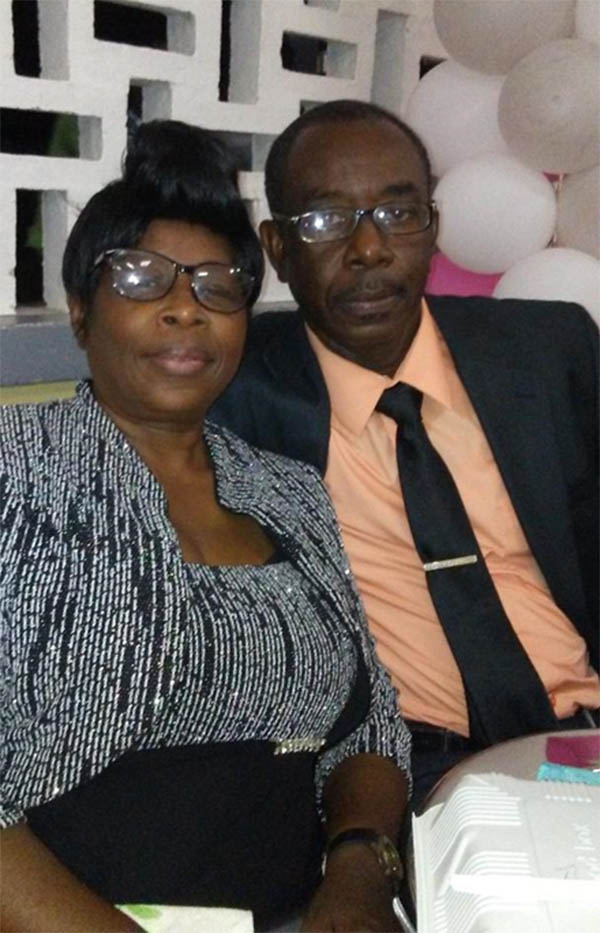

Mitford Ward’s excursion into private enterprise had its roots in the realisation that the country’s high cost of living renders the returns from salaried employment altogether inadequate to meet one’s needs. “It became difficult to live comfortably on a salary,” he says.

Fortunately, this discovery that agro-processing was an option did not give rise to the necessity for him to reinvent the wheel. As a young man in his home village of Lightown on the East Bank of Berbice, during the early 1980’s, he had developed an interest in agro-processing. That interest, he says, coincided with the continual worsening of a crippling economic crisis in Guyana. In a sense, circumstance pushed him in the direction of his present entrepreneurial pursuit.

Mitford’s own venture into agro-processing was part of a wider pursuit of self-employment undertakings by individuals and families seeking subsidies to modest earned incomes. Access to land and what in the cases of many families, had been a background in farming, made agriculture one of the more popular options.

Those were the times, Ward says, when in his own community and in others where agriculture was the primary entrepreneurial pursuit, there arose conflicts between livestock farmers and cash crop farmers. The disputes, he says, arose primarily out of the fact that the two sets of ventures often took place cheek by jowl with each other. Inevitably, the invasion of farmlands and the destruction of crops arising out of the indiscriminate wandering of cattle became an issue.

In Mitford’s instance the necessity to afford the cows his full time attention in order to prevent the destruction of crops robbed him of the time he needed to pursue his own planting pursuits. The option he choose was to engage in agro-processing pursuits by night after having secured his cows.

He recalls that the particular circumstance of Guyana’s loss of the United States’ PL 480 facility which allowed for the supply of wheat and the consequential enormous increase in demand for locally produced bakery products served as a catalyst for his entry into agro-processing. Ward recalls that the absence of imported wheaten flour became the subject of considerable controversy in Guyana, even though its absence was responsible for the awakening of a spirit of self-reliance and inventiveness, a circumstance that brought out a great deal of creativity in the local productive sector. Thereafter, a substantial part of private enterprise subsisted through the pursuit of agro-processing and manufacturing ventures that circumvented the wheaten flour which had now become a banned item.

Ward recalls that it was “around 2000” that he set aside his agro-processing pursuits and went to work as a Probation Officer until 2012.

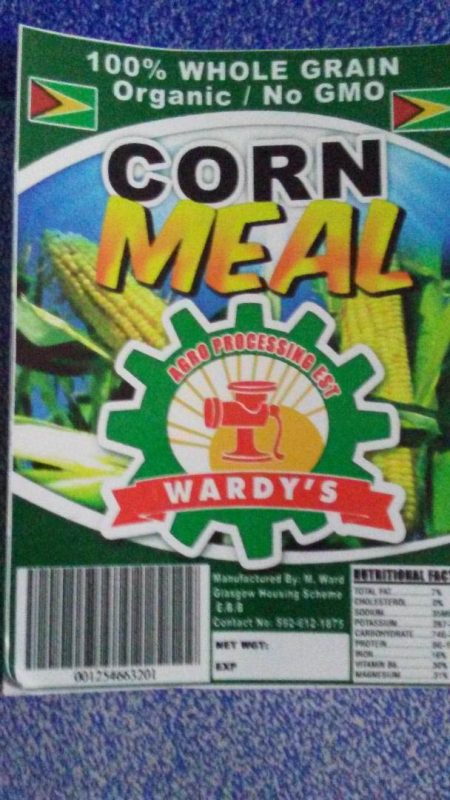

The agro-processing ‘bug’ had, however, already ‘infected’ him. Upon retirement he returned to the pursuit, re-opening his manufacturing enterprise at 1354 Glasgow Housing Scheme, East Bank Berbice, and adding to his product range. These days his now well-known Wardy’s brand produces a range of flours manufactured from plantain, cassava, eddo, and sweet potato, as well as moringa powder. While distribution is limited largely to markets, supermarkets and groceries in Berbice, Ward disclosed to Stabroek Business that he plans to make a marketing foray into the capital soon.

Technology, Ward says, continues to lag badly behind the requirements necessary for the sustained growth of the agro-processing sector. Here he cites the high costs associated with reaching the packaging and labelling standards necessary to be competitive on the international market. More fundamentally, he points to the high costs of acquiring basic equipment associated with the processing of product. “Appropriate equipment like driers is beyond the reach of many agro-processors. I have had to fabricate most of my equipment,” Ward says. He also cites the limited availability of capital as a significant constraint.

Still, Ward says, he does what lies within his power to ensure the maintenance of a standard. His products, he says, are manufactured under “strict hygienic conditions that include the careful washing and indoor drying of raw materials before these are moved to the milling process.

Ward secures his raw materials from a wide range of sources including farmers on the East Bank Berbice, Canje and Berbice rivers and occasionally from farmers in the Pomeroon and North West District.