(Scidev.Net) – Almost 130 countries are yet to receive a single COVID-19 vaccine dose, as ten high-income countries secure the majority.

This past week, the first COVID-19 vaccine doses from the United Nations-led COVAX initiative arrived in Africa. This is a long-awaited piece of good news in a climate where vaccine procurement for developing countries has been hampered by empty promises, delays, infrastructure challenges and prejudice.

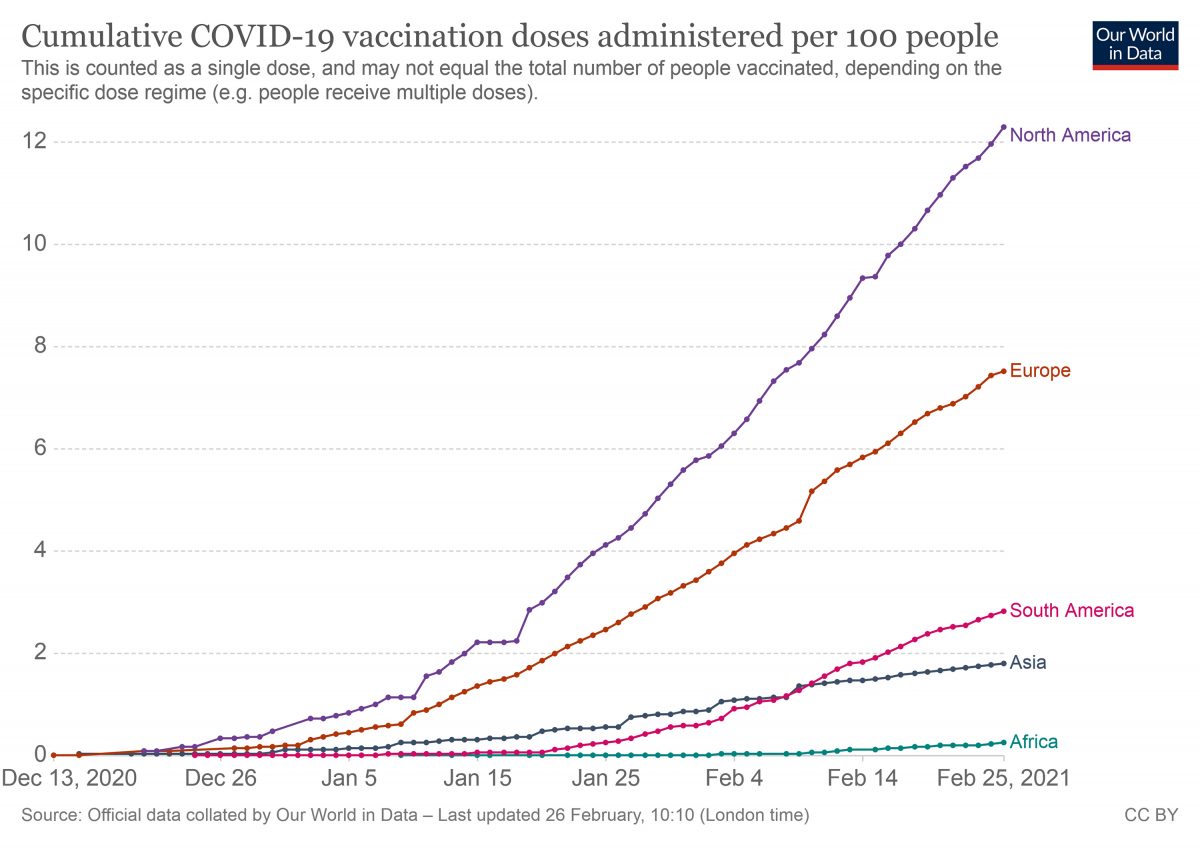

While many richer countries have begun vaccinating their populations in earnest, the world’s poorest have been left behind in the global vaccines arms race. This disparity was highlighted by Henrietta Fore, executive director of Uni-cef, and Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, World Health Organization (WHO) director general, in a joint statement.

While ten countries had secured 75 per cent of the 128 million administered doses, “almost 130 countries, with 2.5 billion people, are yet to administer a single dose,” they said.

Those differences are not a coincidence. The ten countries that have dispersed the highest number of doses so far are developed countries that account for 60 per cent of global gross domestic product, according to the WHO.

These countries, according to global research and data analysis outfit Our World in Data, are the United States, Canada, China, the United Kingdom, Israel, the United Arab Emirates, Italy, Russia, Germany and Spain. Canada has acquired enough doses to vaccinate every citizen five times.

In contrast, most of the countries where no vaccine doses have been administered also report the highest levels of poverty. They are located mainly in Sub-Saharan Africa, Latin America and South-East Asia.

Health specialists now warn vaccine disparity in the developing world could threaten progress against SARS-CoV-2 in the global North, even as wealthy countries look set to immunise their populations by 2022.

“Fragmented and preferential access to the COVID-19 vaccine suggests human life is not the same across the world,” said Joachim Osur, technical director at Amref Health Africa and dean of the School of Medical Sciences at Amref International University in Nairobi.

“It boils down to a moral and ethical question [rather] than a medical or economic one, as vaccine nationalism seems to override equity globally,” he told SciDev.Net.

Osur argues it could be counterproductive for the global North to overlook vaccine progress in poor countries.

“We live in a global village, as it were, and by ignoring humanity interconnectedness, governments are ultimately rendering a disservice to their own people, those they seek to protect,” said Osur.

To address these challenges, the WHO and partners established the COVAX initiative, a global alliance to accelerate the development of COVID-19 vaccines, and to guarantee fair and equitable access for every country in the world. COVAX aims to secure doses for at least 20 per cent of populations in more than 180 countries.

Despite its optimistic objectives, several specialists say that COVAX will have limited impact if there is no incentive for international cooperation to balance access to vaccines.

At the G7 Early Leaders’ Summit (19 February), governments announced a doubling of funding for COVAX, including about US$1.2 billion from Germany and about $600 million from the European Union, plus $2 billion from the United States for 2021.

“A global vaccination campaign is the only road out of the pandemic,” said Germany’s economic cooperation and development minister, Gerd Müller.

“It must not fail for lack of financing. Both for humanitarian reasons and in our own interest. Because it will not be enough to control the spread of the disease only within Europe. Otherwise it will come back — possibly in even more dangerous form.”

From the perspective of developing countries, these and additional vaccine pledges from the UK and France are positive news, said Agathe Demarais, global forecasting director at the Economist Intelligence Unit.

“[B]ut they will probably represent only a drop in the ocean. Most poor countries will rely on COVAX to access coronavirus vaccines, but so far the programme has proved disappointing,” said Demarais.

High expectations, low results

With a few exceptions, developing countries have been left behind in the procurement, distribution and administration of COVID-19 vaccines.

In Egypt, the health minister announced that vaccinations would begin by the second or third week of January after receiving 50,000 doses from AstraZeneca. But not a single dose has been allocated to the public so far and only 1,300 doses had been administered to medical teams by 29 January. The latest announcement from authorities was that the roll out would begin in March.

In Argentina, President Alberto Fernández publicly promised that ten million people would be vaccinated by February. But as of 17 February, only 633,975 doses have been distributed, with less than 392,000 people receiving the required two doses.

In Kenya, the national COVID-19 immunisation programme has been put off several times since December. The government announced on 12 February that it would roll out the AstraZeneca vaccine by mid-February through the COVAX facility, but due to supply backlog by the manufacturers, vaccines have not arrived yet. A leaked confidential government document circulating in local media indicated Kenya may have to wait until the second quarter of 2022 to receive its first doses.

A similar pattern has emerged in South-East Asia. Aside from Indonesia and India, the region has yet to begin vaccinating its population. Cambodia, Laos, Myanmar and the Philippines are the laggards in the region, as they do not have clear schedules for when immunisation programmes will begin.

Delays in the arrival or distribution of jabs are just one part of the problem. Many countries have already faced the challenge of receiving far fewer doses than they require.

This is the case in Mali, where the government announced on 21 January that it had placed an order for 8.4 million doses of vaccine (in addition to 1.5 million doses from the COVAX initiative), but that the first deliveries are not expected until the end of March.

According to the Mali authorities, this quantity will vaccinate 4.2 million people with two doses each — just 20 per cent of the country’s 20 million inhabitants.

This is the general trend across Africa. In French-speaking Sub-Saharan Africa, the Democratic Republic of the Congo has the lion’s share with seven million doses, for a population of around 84 million. Cameroon and Côte d’Ivoire, with a combined population of around 25 million, will receive two million doses.

“We are seeing this in a lot of countries — the uncertainty of constantly receiving contradictory messages or, for example, amounts of doses that are promised, which in the end don’t arrive,” Cristian Castillo, a professor of economics and business studies at Spain’s Universitat Oberta de Catalunya (UOC), told SciDev.Net.

“Part of that uncertainty is caused by the pharmaceutical companies, which have not yet reached firm and real commitments as to the quantities they will be able to produce.”

On 4 February, Matshidiso Moeti, the WHO regional director for Africa, announced that the free distribution of vaccines through COVAX would begin in February with 90 million doses, enough to immunise only three per cent of the African population. The aim to vaccinate 20 per cent of African citizens will be possible by the end of 2021.

But, Léopold Gustave Lehman, immuno-parasitologist at the Faculty of Sciences of the University of Douala in Cameroon, says that the COVID-19 vaccine is not the priority for some countries in Sub-Saharan Africa now.

“Our priorities would be to put the money intended for the purchase of this vaccine in the fight against malaria and other infectious diseases. Because, the prevention of these diseases is a concern that requires more attention,” he said.

Cocktail of challenges

There are a range of factors that have impeded vaccine access in developing countries. A non-peer reviewed analysis (10 February) by the Argentinian Network of Health Researchers, described that in Latin America these factors include saturated health systems that are on the verge of collapse in some countries, such as Colombia and Peru.

For Belén Herrero, a researcher at the Latin American Faculty of Social Sciences (FLACSO) in Buenos Aires and lead author of the analysis, false promises arise when countries overestimate their possibilities to obtain the vaccines, and refuse to admit their limited resources and capacity for negotiations.

Cristian Castillo says logistical difficulties fall into three categories: vaccine environmental conditions, transport infrastructure, and safety.

For instance, mRNA vaccines, such as the ones developed by Pfizer/BioNTech and Moderna must be transported and stored at temperatures below freezing. That requirement “multiplies up to five times the cost of transport compared to conventional freezers”, so it is to be expected that only “countries with strong economic potential” would be able to afford these vaccines, he said.

And although these vaccines could be adapted to higher temperatures and other approved vaccines can be stored between two and eight degrees Celsius, a cold chain is still required. Many developing countries lack these facilities.

That is why transport matters. Castillo points put that in Africa, air freight transport is almost non-existent, which inhibits speedy delivery of vaccines to remote areas.

In addition, African airport charges are among the highest in the world.

Similar challenges appear on land. “We find roads difficult to asphalt and others that, even if they are, lack the necessary maintenance to facilitate their circulation. This is a challenge that makes it even more difficult to get the vaccines to the different points of use on time,” Castillo said.

In terms of security, Castillo noted that vaccine shipments can become a clear target of organised crime syndicates and corrupt officials and should be deployed alongside a security network to ensure that the vaccines reach their destination.

Conditions for accessing vaccines are especially challenging for countries in conflict, such as Syria, Yemen and Libya, where hospitals and health systems are in crisis.

Since these countries may not have the resources to engage in direct negotiations with pharmaceutical companies, they are totally dependent on what the COVAX facility will provide.

“The philosophy for which the COVAX facility was established is to provide assistance to the neediest countries, and of course the countries in conflict come first,” said Ahmed Al-Mandhari, the WHO Eastern Mediterranean regional director.

For Tammam Aloudat, the deputy medical director at Doctors Without Borders, it is important to keep that promise. He told SciDev.Net that conflict zones were key to contain the pandemic. If they are neglected, they will be a source of new waves of infection, both in their regions and worldwide.

The final twist in the cocktail of challenges for the developing world is its political vulnerability and pandemic denialism. In Peru, nearly 500 people, including former President Martín Vizcarra as well as other top politicians and members of their families, were secretly vaccinated with a batch of 3,200 doses of Sinopharm vaccines sent in addition to those officially planned for use in a clinical trial at Cayetano Heredia University.

In Argentina, the former health minister who was in charge of the country’s COVID-19 strategy, Ginés González, also resigned after it was revealed he authorised vaccines for politicians, journalists and business heads who were not in priority groups.

Low vaccination rates have so far been seen in countries where political leaders downplayed or denied the scale of the pandemic, such as Brazil and Tanzania. “Those countries, which coincidentally are developing countries, whose politicians have not been very favourable to publicly acknowledge the problem [of the pandemic] also contribute to the difficulty in [vaccine] distribution,” Castillo said.

“If a distribution process is finally achieved with global financial aid, but once we have the doses there is no participation of the population, it is going to be nonsense. And this is where politics plays a fundamental role in sending the right message about the importance of getting vaccinated.”

Global collaboration: The real solution?

In the face of global data that reveals some wealthy countries are hoarding vaccines while poorer countries wait for access, world health leaders and organisations, including the WHO, have launched sharp criticisms.

“I urge countries that have contracted more vaccines than they will need, and are controlling the global supply, to also donate and release them to COVAX immediately, which is ready today to rollout quickly,” said Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus at a press conference in January.

Similar voices have urged regional collaboration to create equal access to vaccines.

For the Argentinian researcher Belén Herrero, in this health crisis cooperation and regional integration become key elements to enhance the capacity of countries by complementing actions, not duplicating efforts.

“Such actions could have contributed, for example, towards strengthening cross-border cooperation; flights carrying equipment and vaccines could be arranged, joint negotiations would facilitate purchases and acquisitions with vaccine producers, all while strengthening regional capacities,” she said.

Cristian Castillo agrees: “It would be useless for the so-called ‘first world countries’ to worry about vaccinating their own population but forget about these developing countries. It would not make any sense …we need to collaborate with these countries.”

While noting that the COVAX facility was an important initiative to assist lower-income countries to access COVID-19 vaccines, Joachim Osur, from Kenya, says it relies more on the goodwill of wealthy countries than on substantive legal and contractual mechanisms.

“And that is where we encounter a problem,” he told SciDev.Net.

“Should the UK for instance agree that vaccines manufactured in its own territory be transported to other countries while its own citizens need it?

“And if the US has enough money to purchase vaccines for its citizens who are dying daily, should it go slow so that Africa, where the pandemic is more protracted, can also receive some doses?”

Strengthening health systems

But, Africa should have been more proactive in securing COVID-19 vaccines, says Peter Ofware, the Kenya director at health and human rights organisation Health Right International.

“From where I sit, Africa lost the vaccine plot from the moment they allowed themselves to be subject to charity,” he says.

Ofware says collaboration is indeed needed, but it should focus on strengthening the political and technological development capabilities of poorer countries.

“The continent [Africa] should have forged collaborative deals with pharmaceutical companies from the word go so that some of the vaccines could be manufactured, cheaply, locally, so they can have easy access, like what is happening in India,” he said.

Cuba, says Herrero, is another example of a country that has developed vaccine independence and sustainability.

“Cuba’s progress in developing its own vaccines shows the importance of supporting scientific research, promoting technological development, strengthening and investing in health systems, in pursuit of sovereign health systems and the population’s right to health,” wrote Herrero in her analysis.

While the world is facing almost 1.5 million deaths from COVID-19, it is also in the countries where there is the greatest devastation that a perspective seems to grow stronger: that the scientific and technological development must be at the centre of discussions to contribute to alleviating the global emergencies of the future.