‘O where ha’ you been, Lord Randal, my son?

And where ha’ you been, my handsome young man?’

‘I ha’ been at the greenwood; mother, mak my bed soon,

For I’m wearied wi’ hunting, and fain wad lie down.

‘An wha met ye there, Lord Randal, my son?

An wha met you there, my handsome young man?’

‘O I met wi my true-love; mother, mak my bed soon,

For I’m wearied wi’ hunting, and fain wad lie down.’

‘And what did she give you, Lord Randal, my son?

And what did she give you, my handsome young man?’

‘Eels fried in a pan; mother, mak my bed soon,

For I’m wearied wi’ hunting, and fain wad lie down.’

‘And wha gat your leavins, Lord Randal, my son?

And wha gat your leavins, my handsome young man?’

‘My hawks and my hounds; mother, mak my bed soon,

For I’m wearied wi’ hunting, and fain wad lie down.’

‘And what became of them, Lord Randal, my son?

And what became of them, my handsome young man?’

‘They stretched their legs out an died; mother, mak my bed soon,

For I’m weary wi’ hunting, and fain wad lie down.’

‘O I fear you are poisoned, Lord Randal, my son!

I fear you are poisoned, my handsome young man!’

‘O yes, I am poisoned; mother, mak my bed soon,

For I’m sick at the heart, and I fain wad lie down.”

‘What d’ ye leave to your mother, Lord Randal, my son?

What d ‘ye leave to your mother, my handsome young man?’

‘Four and twenty milk kye; mother, mak my bed soon,

For I’m sick at the heart, and I fain wad lie down.’

‘What d’ ye leave to your sister, Lord Randal, my son?

What d’ ye leave to your sister, my handsome young man?’

‘My gold and my silver; mother, mak my bed soon,

For I’m sick at the heart, and I fain wad lie down

‘What d’ ye leave to your brother, Lord Randal, my son?

What d ‘ye leave to your brother, my handsome young man?’

‘My house and my lands; mother, mak my bed soon,

For I’m sick at the heart, and I fain wad lie down.’

‘What d’ ye leave to your true-love, Lord Randal, my son?

What d ‘ye leave to your true-love, my handsome young man?’

‘I leave her hell and fire; mother, mak my bed soon,

For I’m sick at the heart, and I fain wad lie down.’

– Traditional, Anonymous

One of the interesting types of poetry existing in the great corpus of English literature is the ballad; more particularly, the old Scottish or English ballad. It belongs to the magnificent store of oral literature (folk poems) that has survived, some of which probably date back to the Middle Ages. Various factors in the political context of these poems provide profoundly interesting studies.

This one, “Lord Randal”, has many variants. The version printed here was recorded in 1803 and our source is the Oxford English Dictionary. But the poem itself is much older than that, and there are recordings of it transcribed and printed in the sixteenth century. There are also many different versions existing in different countries, although its origin is Scotland. These forms of oral literature developed because they were sung or recited in communities and taken to different regions and countries by performers such as troubadours/ singers. The various performances and recitations over a long period of time, and when recited or sung in different places, caused many variants – changes in some words or phrases, or even in whole stanzas. One known version has only five stanzas, while this one has ten.

Such variants have to do with the way these poems were composed and transmitted. They are anonymous; they are not attributed to any authors. It is not known who first composed them, or if the composer was just one person, because they were not written down just passed along among groups of people. Traditional folk poetry of this sort is regarded as having been composed by the communities from which they came. As they were repeated or performed over the years, or moved from one geographical locality to another, pieces were changed, added in or left out. To a very great extent, the survival of oral poetry depended upon the memory of those who perform it or hear it.

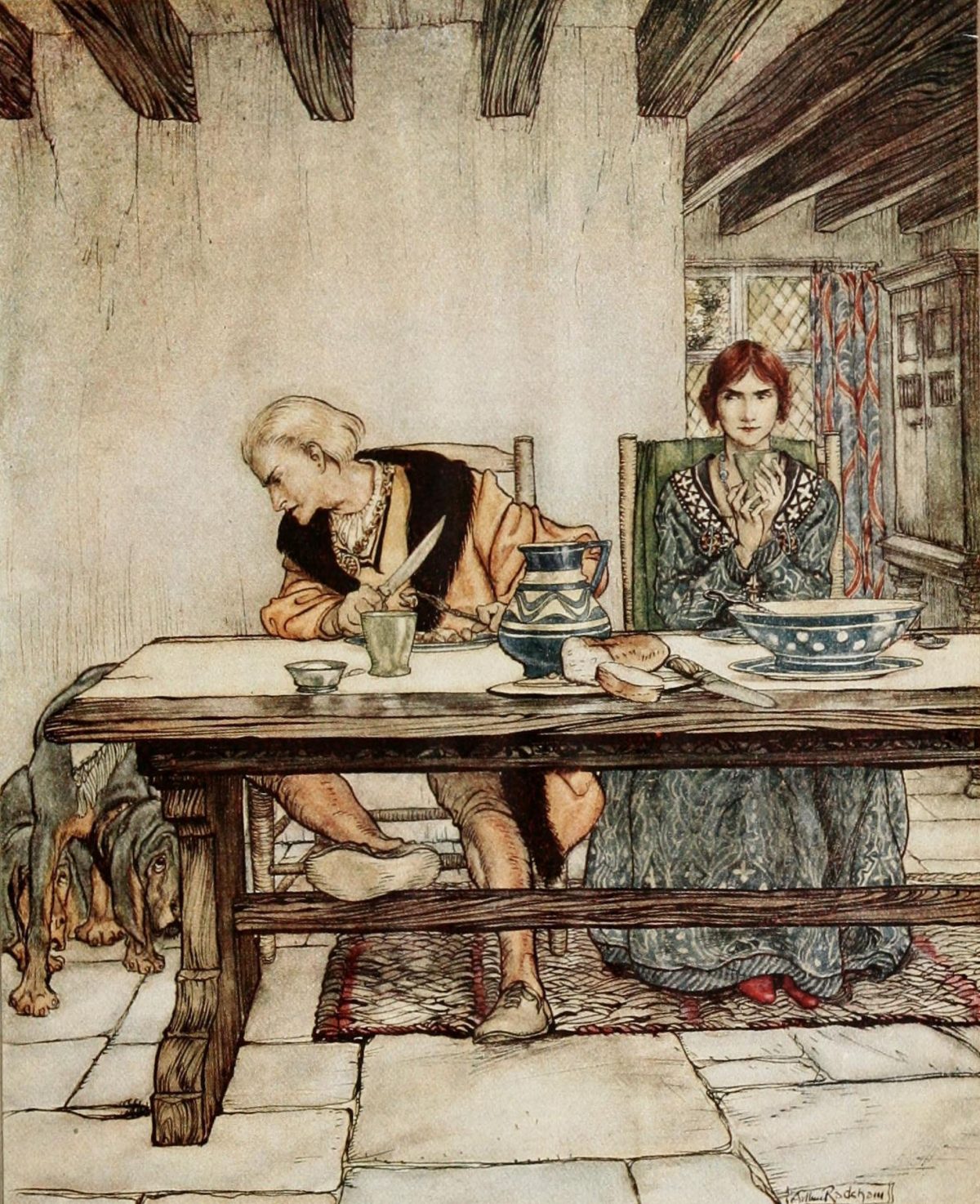

There are certain characteristics that are typical of the form, and this may be arising from the political context. It is to be noted that these poems generally tell stories whose characters belong to the aristocracy. Although the poems originate and circulate among the folk, the stories are not about them. This one is about a young lord talking with his mother. This establishes his aristocratic identity. But, as it is in other poems where that is not so obvious, there are other things that establish class. The most common is references to hunting, which was the past-time of royalty, the nobility and the rich. Every nobleman would have horses, and would be perpetually armed with a sword. Additionally, he would have hawks and hounds, faithful, loyal animals that take part in the hunt.

The society in which the poems were created was feudal. The majority of the population were serfs or peasants, but they did not matter as people. It was the king, royalty and the noblemen who were important as characters worthy of tragic study or in tales or legends. In fact, it is believed that many of the ballads actually tell about events that happened. But theirs was a heavily class-conscious society, reflected in the characters about whom stories are told. You will find the same in the fairy tales that developed around the same time.

What is of great interest is the predominance of tales of love among the ballads, but to be more specific, tales of false love. While there are some about true romances, the stories are more likely to be about deception, disloyalty, unfaithfulness, betrayal and even murder. What is even more remarkable is that the woman is usually the villain. She is the one who is false and might murder her lover in order to go off with another.

Lord Randal’s “true love” is one of those. It turns out in the story that she poisoned him, leaving him heartbroken and dying. The related political context also has to do with the courtly love tradition, which was topical while the ballads developed, and popular as a topic for poetry. This tradition involved ladies of the upper classes, and love affairs. It is not unlikely that an attitude to women which typified them as fickle and unfaithful would trickle down from the political hierarchy to the serfs and peasant classes.

Lord Randal’s story is told in accordance with the characteristics of this form of poetry. Because this is oral poetry, there are certain strategies that are used to create interest and to aid memory. People have to easily remember it in order to tell it to others. Additionally, it needs to be easy to listen to, since it was always orally transmitted.

A number of features results. There is usually an air of mystery, in that the story is not told outright or made entirely clear. The plot is released in increments and lines are repeated with a slight difference each time. Each repetition adds another development in the plot. In “Lord Randal” there are lines of repeated questioning by the mother, before we learn what really happened to the young lord; he reveals the story in increments.

Another characteristic is the use of dialogue and drama. The story-telling is dramatised through dialogue. Rather than a narrative, we get a dialogue between a naïve questioner and an experienced respondent. In this poem, the lady does not know what happened, but in order to find out she questions her son, who knows the answers but is reluctant to give them. He starts by claiming that he is weary with hunting. But it could also be that he is using metaphors: “I’m wearied with hunting and feign would lie down”.

The repetitions continue right through the dramatic poem, but with strategic changes of words as the dialogue progresses. This is a great aid to memory as well as to the oral qualities of the poem since its audience is hearing it and these techniques keep the audience connected and interested.

Another important factor in the poem is the language. It is in the spoken language of the people who created it, the Scottish dialect. The language basically confirms its identity as belonging to the folk, despite the upper class setting of the story. As printed here, it is a partly translated, Anglicised variety of the Scottish language. Different versions of the poem will have linguistic variants depending on the transcriber and translator.