The South Rupununi Conservation Society (SRCS) is imparting traditional knowledge covering indigenous skills, culture and dialects that are fast seeming to fade to 240 youths from eight villages in the South Rupununi and the Central Sub-district.

The SRCS is a small grassroots non-governmental organization which was found in 2002 when the Red Siskin, an endangered bird species, was discovered in the South Rupununi. Since then its members have placed environmental education at the top of their priorities list. They believe that a lot of the destructive habits that occur in the South Rupununi such as overharvesting, pollution, and habitat destruction could be addressed by environmental education.

Neal Millar, who coordinates the traditional knowledge classes told the Stabroek Weekend, “In 2018, we were fortunate to be supported by the Sustainable Wildlife Management (SWM) – Programme, Guyana to design an environmental education curriculum for schools in the South Rupununi. SWM is an African, Caribbean and Pacific (ACP) Group of States initiative, which aims to tackle the issue of overhunting of wild meat.

“After initial consultations with some communities, our Environmental Education Facilitator, Miss Alyssa Melville, designed a curriculum that covered one school year. A curriculum was designed for secondary school level and another for primary school level. The curriculum was split into 3 terms with students learning about local plants and animals in the first term, the environment of the Rupununi in the second term and their language, culture and stories in the third and final term. There was one lesson each week and the classes were taught by teachers from the schools.

“In September 2019, after we trained the teachers on how to use the curriculum, we implemented the curriculum to three primary schools and one secondary school in the South Rupununi. We managed to implement both the first and second terms, however in March 2020 the schools were shut due to the pandemic and we were therefore not able to implement the third term. The Ministry of Education had given us permission to teach the lesson during a spare slot in the secondary timetable and after school for the primary school level.”

Millar explained that they waited for schools to reopen to so that the third term could be executed but by October last year they realized that this would not happen anytime soon. Still excited about implementing the third term, they decided to go for it but over a longer period of time.

He shared that community members have lamented that traditional knowledge about indigenous skills was being buried with the elders who pass on. “As we are aware, traditional knowledge is interlinked with environmental education and we were therefore fulfilling two goals in one,” Millar said.

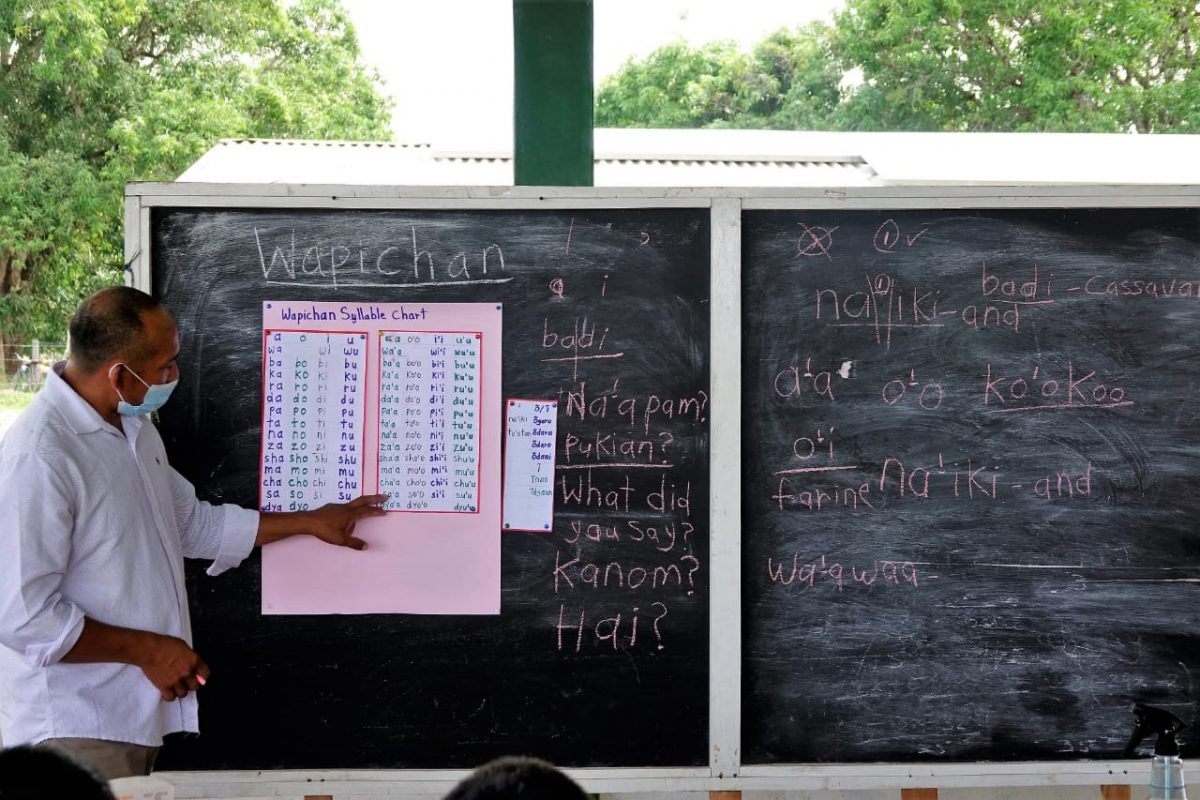

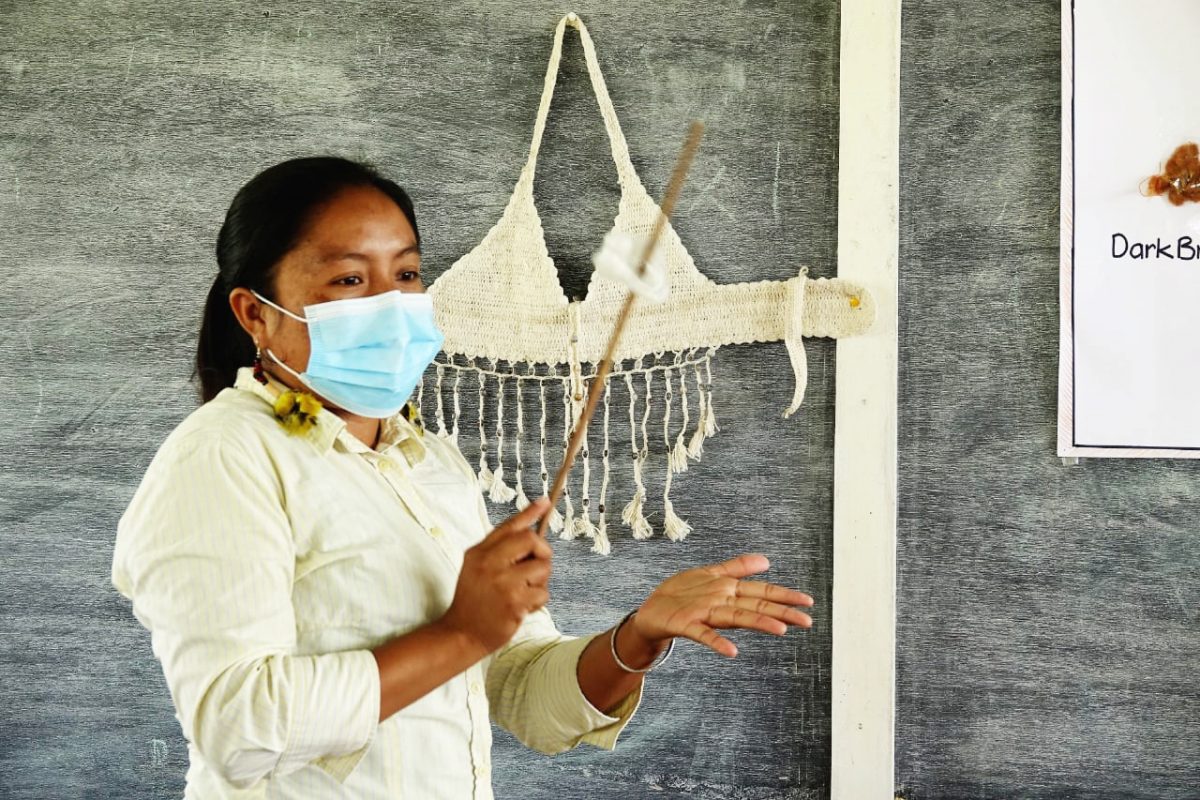

Between November and December 2020, SRCS members visited eight villages, Kumu, Shulinab, Sand Creek, Katoonarib, Sawariwau, Aishalton, Maruranau and Shea, consulting with the councils there about going forward with the curriculum and seeking ideas on how best they could continue executing the programme. They arrived at the decision that each village would choose the three skills they wanted their youths to learn as well as identify three persons in the village who could teach them. The skills are cotton spinning, basket weaving, arrow making, cow skin crafts, Wapishana and Macushi languages, storytelling, traditional medicine and woodwork.

As it relates to the structure of the lesson plan, for lesson one, the designated skill will be introduced, and its history provided along with its importance and physical examples. For lesson two, where applicable, students will take field trips to gather the necessary materials for their skill: cotton, arrow cane, or tibisiri for basket weaving. During lessons three to six, students will make one or two crafts with their raw materials and/or learn the language basics.

“The lessons started at the end of January 2021 and are currently scheduled to run until June 2021. Each village selected 30 students for their lessons, totalling 240 students across the eight villages. The 30 students have split into groups of 10. For the first six weeks, each group attends one class per week where they learn one skill and by the end of the six lessons, they make a small craft, eg a baby-sized hammock or sling, an arrow, a basket etc. After six weeks, the groups rotate to the next skill and the teacher [imparts] the same six lessons to the new group. Once the groups complete all three skills (18 classes), we are hoping to hold an exhibition class in each village where the students showcase what they have learnt to the rest of the village. However this will depend on COVID-19 restrictions,” Millar said.

Each group of ten students is housed in three different buildings for each village as a way of adhering to social distancing protocols. For instance, in Katoonarib, the group of students doing craft are being taught in a benab, while the second group learning cotton spinning are at the community centre and the third group doing language are at the village office.

For each lesson, the teachers will focus on how the materials used relate to sustainable wildlife management. Millar shared that the spindles used for spinning cotton are made from the spines of river turtles, while monkey bones are the

traditional tools used for stripping the tibisiri for basket weaving. The animals used to be killed and their bones harvested. He said that while they are trying not to change the traditions of the indigenous tribes, they look for sustainable ways to upkeep them. Most of the students learning to spin cotton have a spindle made from the river turtle spine, but they are borrowed from the older villagers. If someone needs to have one today, it can be fashioned easily from PVC pipe. Various knives are used as substitutes for monkey bones.

“We realise that six lessons for each skill is not a lot of time and the students will not have mastered the craft,” Millar said. “However the purpose of the classes is to spark that initial interest in the children and to get them interested in their culture and install a sense of pride and empowerment. Any elder in a village will tell you that most young people are losing interest in their heritage and are more concerned with technology and money etc. But from these classes we are seeing that children really do want to learn, and it seems like they have just not had the opportunity. And in some cases parents didn’t think their children wanted to learn but really the children were just shy to ask. The children are thoroughly enjoying themselves and we have lots of children who want to join the classes in their village, but we are limited to 30 due to trying to stick to COVID guidelines.”

He added that village elders are thrilled to see their youths involved in skills, culture, folk stories and their language as part of restoring their dying culture. As it relates to the language aspect of the classes, not every village signed up for these sessions as in some villages, everyone speaks the traditional dialect there. Millar pointed out that most of the villagers of Sawariwau speak Wapishana. A large percent still only speak the dialect and do not know English. He explained that in school, the teachers are bilingual and would speak Wapishana when teaching the first and second graders so that teaching can be more effective. They gradually introduce English to the children.

The SRCS classes, Millar stated do not affect the regular school curriculum as students are only required to attend classes on average about two hours a week, more or less. As it relates to the children working the Ministry of Education curriculum, he said that materials are printed for them. The 240 students in the SRCS programme are aged 10 to 17 years old. Asked what will happen with the programme should school start following the Easter vacation, Millar said it is possible the classes will be held after school or on the weekends.

SRCS is hoping to secure more funding to keep the classes going. Despite them only having been run for a little over a month, the positive feedback has been overwhelming. “Everyone we have spoken to has commented about how important this initiative is and that they want to see it continue,” he said. “Due to funding, we were only able to implement the project in eight villages. However many other villages have approached us asking to start the project in their village. So we will try our best to source funding to continue the classes and to expand to other villages. As mentioned, the project is currently funded by SWM, however it seems likely that schools will reopen by September 2021 so we will have to revert to using our funds from SWM to continue implementing the Environmental Education Curriculum, which does also have a component of this. However the feedback we have gotten has made us determined to find funding to continue the traditional knowledge classes on a weekly basis. Now that we have started, we have a good idea of the costs to run the classes.”