The previous column (April 4: ‘The government’s overdraft at BoG, the fiscal deficit and corruption’) explained that the government’s fiscal deficit — which must not be confused with current account deficit as one online commenter did — has to be financed by (i) borrowing, (ii) seeking foreign grants, (iii) using previous savings, and/or (iv) creating money from its deposit at the Bank of Guyana (BoG). Nothing stops the government from using a combination of the four sources of finance. However, the money financing out of the BoG account in a given year cannot exceed the entire fiscal deficit (revenues minus spending).

As I have shown previously, the amount of money exiting the BoG account exceeded the fiscal deficit in 2015 and 2018. In other years, central government used some combination of debt and BoG finance. For example, in 2014, 88.3% of the deficit was financed by running down the BoG account, while in 2019 the number was 51.8%.

The BoG account is the most special account in the land. The government cannot create money out of spending from the Consolidated Fund, for example. It does not mean that the Consolidated Fund cannot under certain circumstances be used for monetary management, as is the case with the Treasury Tax and Loan Accounts (TTLA) of the United States Treasury. The law prohibits the US federal government from spending out of the TTLA. However, the Treasury (their Ministry of Finance) often transfers money from the TTLA (their Consolidated Fund) to the Treasury’s account at the Federal Reserve (their BoG account). The federal government can only spend out of its account at the Federal Reserve.

This raises an interesting question. Is the Guyana government allowed discretionary spending from the Consolidated Fund? We know Parliament has to approve any spending from the account. A lot of shenanigans can be done via the Consolidated Fund (CF). As some readers might remember, I complained a few years ago in this column space that the summary table of the CF has been removed from the Estimates.

A better designed government accounting system would allow for the Consolidated Fund to be the receiver of all tax and other revenues (as the Guyana constitution requires), including revenues drawn down from the proposed Natural Resource Fund (NRF) (whatever happened to the NRF?). Absolutely no spending should be done from the CF, approved or discretionary. However, all government spending can and must be done only from the BoG account. The Minister of Finance can instruct the transfer from the CF to the BoG account, as is done with the equivalent accounts in the United States and other economies. This provides a better tracking system, as well as another instrument for monetary stability in times of financial crisis. Moreover, such an accounting system will provide for a better integration of monetary and fiscal policies.

Another question has been raised by observers regarding my April 4 column: isn’t the central bank independent? It turns out that mainstream macroeconomics usually throws the light in directions it does not want us, particularly marginalized people, to look. Central bank independence is a misnomer. The central bank is never truly independent since it is the government’s bank. That is why one of the first acts of independence is to establish a central bank. The Chair of the Federal Reserve, for instance, cannot stop a payment from the federal government that was approved by Congress. The Chair cannot stop the transfer of funds from the TTLA, which are in commercial banks, to the government’s account at the Fed. Monetary sovereignty means there is deep coordination between the central bank and Ministry of Finance.

Central bank independence means that the Bank must be free to determine its target variable such as the exchange rate and/or interest rate. It must be free to take countervailing actions to prevent excessive government spending from destabilizing the economy. There are numerous ways central banks can accomplish this task and it must be free from political pressure as it seeks to stabilize the economy. However, once Parliament approves a spending, including a drawdown from the NRF, the BoG is not in a position to resist the payment.

Specifically, as it relates to the overdraft at the BoG, the Governor and his staff can only figure out that account is being used in excess of the deficit after the data have been aggregated. It would be hard to figure this out beforehand. Around the world, spending from the government’s central bank account is a standard operating procedure. What is not standard procedure is the spending, even parliament-backed spending, directly from the various ‘consolidated funds’.

Let us return to 2015, one of the years when the withdrawal from the BoG was greater than the deficit. Mr. David Granger was sworn in as President on May 16, 2015, meaning that the year was divided almost half and half between a PPP/C and APNU + AFC government. We would like to answer the question as to which party was most responsible for the negative balance exceeding the deficit. This outflow does not include the spending that could have occurred from the CF.

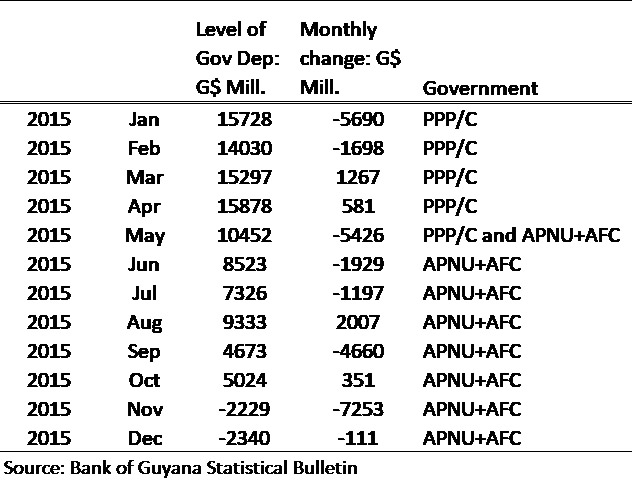

Accomplishing this task requires that we again look at the change in the account balance from one month to the next, and not the end-of-month balance. In other words, we must look at the leakage from the bathtub, not the water level. This is indicated in the table that shows the data from Jan: 2015 to Dec: 2015.

Summing the monthly changes from Jan to April indicates that the PPP/C was responsible for G$5.54 billion, while APNU+AFC was responsible for G$12.79 billion. I would let the reader decide how to apportion the month of May, for which the draw down in the level was G$5.43 billion. Is that a PPP/C or APNU+AFC month?

Nevertheless, there are two interesting pieces of information in the public domain. The first relates to the Amerindian Community Support Officers (CSOs) under the previous PPP/C government. In spite of all the ruckus in Parliament over the almost 2000 CSO officers that the APNU + AFC supposedly defunded, we learned that these people were not official employees of the government (SN: Aug. 20, 2015 ‘PPP/C did not budget to pay Amerindian support officers beyond April’). The CSOs were not contract or state employees, they were offered recurring cash stipends that were not given full account (cash being the key word here).

The second pertains to the D’Urban Park fiasco, a sin which far exceeds that of PPP/C’s cash payments to the CSOs. The Auditor General’s (AG) report noted that no approval was given for a large percentage of the funds used for the project (see SN: Feb 3, 2019: ‘Audit Office still awaiting response from Infrastructure Ministry on D’Urban Park spending’). The non-approved spending was associated with 2015 cheques that were paid.

Finally, and relating to the 2018 negative change that also exceeded the deficit. Another report from the AG noted that the previous government failed to account for G$800 million (SN: Jan 5, 2020: ‘Gov’t failed to account for over $800M spent in 2018’). All these examples only account for part of the observed discrepancies. They just scratch the surface of overspending associated with a broken accounting system.

There is 0.85 probability that I cannot write a column this week. That means I will be back in a fortnight, when I will present some eye-popping data for the last two columns on this issue.

Comments: [email protected]